The Dire Effects of Salt Pan Syndrome

(Marie-mail #58)

MARALAL TO SOUTH HORR

OCTOBER 19

Minus two passengers, we drove to South Horr on dreadful "you've got to be kidding" roads. I was getting used to the routine. We'd rise early, breakfast and break down camp, lurch from side to side at 20 kilometers an hour along terrible roads until lunchtime, have a picnic, then lurch along until it was time to stop and camp again.

We weren't meeting a lot of Africans at the moment, and all of Africa that we saw was covered in a film of grit. Everyone was going a bit stir crazy, but unfortunately northern Kenya features vast expanses of road and not many interesting sights, so there was no way around it.

nothing here but us camels

nothing here but us camels

The highlight of the drive was goading Sam the cook into swearing about injera, the Ethiopia flat, spongy bread that is used in place of utensils. Personally, I like injera, but its slightly sour taste inspires strong reactions. It's a love-it-or-hate-it sort of food.

Tonight's campsite was a wooded area called "Forest Campsite." We set up camp, had showers under an elevated spout in a corrugated tin shack, and stared at the curious tribespeople who had come to stare at us.

You get used to being stared at in rural areas. I had the same

experience in India, and all over Africa. Remote tribespeople don't

have televisions, so they will watch for hours as you do the most mundane, boring things. Watching us flap plates dry, for example, was apparently fascinating.

Eventually, the locals had to go home to their own dinners. We were left alone with our armed campsite guard.

Unfortunately, our guard had taken the pay Mark had given him and purchased some alcohol, which he apparently consumed rapidly as he was now quite intoxicated.

"We have a bit of a situation here," said Mark. He , Tony, and Sam went off to deal with it, leaving us alone to contemplate the dangers of having a drunk armed guard.

The "guard" returned his pay sheepishly and wandered off to search out a nice ditch for a nap. Mark hired a new guard, who armed himself with a bow and arrow.

Gimme!

Gimme!

We practiced the Kenya children's "gimme" motion that night. It's a friendly wave, but a swift twist brings the palm upward, at which point it becomes an outstretched begging hand. We thought Kenyan children incorrigible with their demands for pens and candy. But, we'd soon discover in Ethiopia that we'd seen nothing yet.

SOUTH HORR TO LOYANGALANI

OCTOBER 20

Morning chatter, in Swahili, woke me up. The villagers who had stared at us so intently had returned, and this time they'd brought souvenirs.

Unfortunately for them, we had no major shoppers in our ranks, and we all chose to ignore the impromptu market, opting instead to eat Sam's delicious French toast and disassemble tents.

I sliced bananas onto my French toast and gobbled it up quickly, praising it loudly to encourage Sam to cook it more often (later I discovered his secret was to spoon in a few tablespoons of sugar into the egg batter). I washed and rinsed my dish, then flapped it dry.

"...eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve..." I stopped flapping and the

counting stopped. I resumed flapping. The counting began again.

"...thirteen, fourteen..."

Some village children were practicing their English numbers by

counting my flaps. They dissolved into giggles when I spotted them.

We lurched out into another hot day of driving. A broom fell on me, the highlight of the drive. I braced myself for the excruciating boredom of staring and napping. There were miles of difference between me being on the ground, shoved into a matutu with Africans, and me propped up on a double seat in a bubble of westerners. I felt insulated and disconnected from Kenya, but I knew I'd appreciate a little cultural distance when I got to Ethiopia. From all accounts, I could expect a full-on experience there. Some people called Ethiopia "the India of Africa."

The road was gravel for ages. Finally we hit a more dirt-based track, and then the brilliant green water of Lake Turkana slowly appeared out of the dry, brown and yellow desert. The road winded down to its surrounding palm-filled oasis.

"Jade Sea"

"Jade Sea"

El-Molo Campground, on the edge of Loyangalani, was a fenced-in tree-filled patch of green with a warm swimming pool. The usual elevated spouts were showers, but they were enclosed in atmospheric thatched huts.

oasis campground

oasis campground

I asked Mark for a key to the truck. He proceeded to spend ages putting a key onto a new string for me to wear around my neck and then forgot about me completely and gave it to Charles the Camel-Puncher. I didn't mind -- it gave me license to mock Mark and pout with glee.

I organized a doggy-paddle race in the pool. Trigger turned out to be the best barker in addition to the all-around most-doglike. Later, we dried off and took a walk through Loyangalani's village outskirts.

huts abound

huts abound

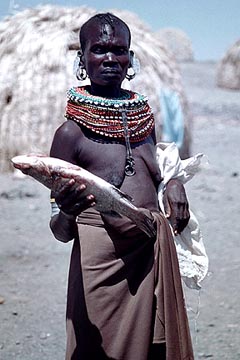

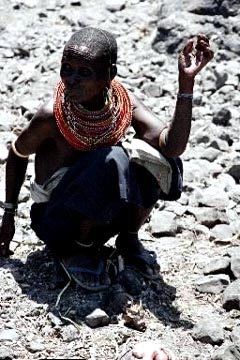

The villagers lived in round, dried-palm huts. The various beads worn by the gaunt village women denoted their marital status, while the single strands of white beads were worn only by widows. As we walked by each home, our local guide would ask if we would like to take a picture.

"Photo?"

"Is there a fee?" We'd invariably ask.

yes, she's a woman

yes, she's a woman

"Yes." There always was.

"No, no photos." We'd had it with trying to work out the ethical

implications of paying for photos, and I couldn't decide if it was

perpetuating exploitation or paying someone a fee for a fair trade.

huts in the desert

huts in the desert

We left the parched landscape of the huts behind us and walked back to camp, where our local guide invited us to a disco.

"It isn't really a disco," he explained. "It's a dance put on by some local guys. It's in the school."

This sounded like it could be either awful or intriguing. Charles, Peter, and I followed the guide to the school. I peeked in through the window.

"Hello!" Three men hung their heads out and gaped at me. Startled, I drew back. They drew closer. I fled for the others, who had walked around to the front door to stare into the school.

There were about thirty men inside, all horsing around while music played.

"Are there any women?" I asked our guide.

plenty of women

plenty of women

He went in to check. He returned a few minutes later.

"There are two in the corner," he pronounced with satisfaction.

"I'm not going in there," I said. Charles and Peter were equally

unwilling to go. We walked back to camp, under the dark palm trees that swayed with the wind.

I crawled into my tent and turned off my flashlight. I zipped open the little blue tent's fly and stared up at the night sky. It was brilliant with clear stars, and I the sound of frogs was just audible over the wind. The days were long and the group suffocating, but the night skies were worth it.

LOYANGALANI

OCTOBER 21

The wind buffeted the tents all night, but it was hot enough that I slept on top of my sleeping bag.

"The little blue tent is going to blow away," I thought as I wistfully zipped it up and left it standing. We weren't moving camp today. But then the sun came up and the wind slowed, and besides, I had staked the tent to the ground.

local tribespeople

local tribespeople

We visited another group of Turkana tribespeople, and then took a motorboat to an island for a view of the "jade sea" and its surrounding stark desertscape. The tribe had the unique distinction of being at peace with crocodiles. In spite of living in the thick of

crocodile country, none of the tribespeople had ever been eaten by a croc. We laughed nervously and suggested they still give their reptilian friends a wide berth.

crocs don't eat them

crocs don't eat them

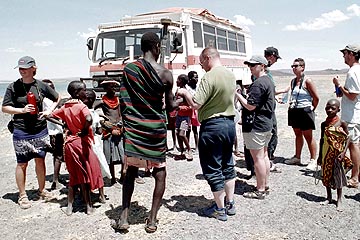

Dragoman had paid a fee for the group of us to take photos, so we were told we could photograph freely in the village. But then several tribespeople asked for more money, so we all gave up and headed back to the truck, still struggling with the inherent ethical dilemma.

souvenir negotiations

souvenir negotiations

LOYANGALANI TO KALACHA

OCTOBER 22

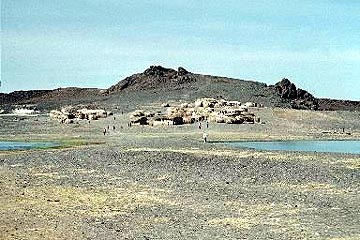

"Remarkable in its tedium," I wrote in my diary during the long drive to Kalacha. There was nothing at Kalacha -- it was just a necessary overnight stop between Turkana and Marsabit, which was itself just a stop on the way to the Ethiopian border.

We got stuck in the gravel once. The crew simply and easily dug us out. Later, a rock wedged itself in between two of our four back tires. Mark pried it out with a tire iron. A little man emerged from a mud hut to jabber Swahili advice at Mark, who gave him a "leave me alone, I know what I'm doing" withering look. The little man turned to me.

"Muskrat? Muskrat?" He seemed to be saying.

"No, thank you," I said politely. "I don't need a muskrat."

Our tires, which had originally belonged to the sick truck Oscar (who was going home to the UK for service) had been shredded along the edges by the volcanic landscape. The rocky desert was dangerous to our wheels.

We were stuck in gravel a second time, but again dug out quickly. We finally reached the small town of Kalacha, where the Kenyans dressed differently and had different facial structures from all the Africans we'd seen to date. They were lighter, with multi-colored scarves, flowing sarongs, and were beginning to bear a resemblance to Ethiopians. Area children would spot us and break into runs, chasing the truck at top speed until we outdistanced them.

Kalacha itself featured some cement huts on a tiny dirt road. It was so remote that it wasn't even possible to replenish our diminishing supplies of soft drinks and beer. It did, however, have a windmill-powered source of water that made the hostile desert a little friendlier. The whole town had water, and we had tin shacks with showers and a nice round swimming pool.

"It's a giant dogbowl!" I declared. "A giant dog is going to come and lick us all to death."

At great personal peril, nearly everyone went for a swim.

Again, it was a night of sitting around talking to my fellow

westerners. Kalacha was small and there wasn't anything to do. It was windy and dusty. We'd be glad to leave it.

KALACHA TO KALACHA

OCTOBER 23

We left Kalacha's giant dogbowl behind us at seven. Mark was intent on reaching Marsabit by early afternoon, as he had to line up a guard or convoy for us to get north to the border. The area had seen violence, and while none of it had been aimed at tourists, it was illegal for us to proceed without an armed escort.

Duva, Dragoman's local Marsabit guide, was with us, along with his tall, heavyset sister and her baby.

We had high hopes for Marsabit.

"I hope there's a launderette," said Monica. "There's only a dry

cleaner listed in the guidebook."

I personally was hoping for an internet cafe. The last one had been in Isiolo.

Marsabit, according to "Lonely Planet," didn't have a lot to offer. Still, it had a few hotels and supermarkets, and was the last "real" town in northern Kenya.

We headed out into the desert, across the dry salt pan. Duva had suggested the salt pan route because the other route was covered in volcanic rock, which had already done serious damage to our tires.

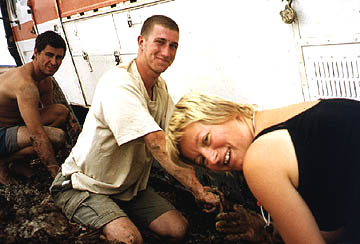

stuck in the mud

stuck in the mud

File under "seemed like a good idea at the time," I thought later. The dry, crusty salt pan hadn't had rain in years, since El Nino. But salt pans, like a camel, saves their water for a non-rainy day, by secreting it under the surface in a thick, damp layer of clay.

middle of nowhere

middle of nowhere

Sam was bored early in the day, and he came back to chat. I asked him about the Dragoman manual's instructions for getting out of bogs. I was suggesting that Nikki's system for driving in sand was best, while he was arguing that it was hard on the steering box.

Suddenly, the truck lurched dramatically to the left, throwing us all about like basketballs. We thudded to a firm, definite halt. Mark tried moving forward and back, but we couldn't move anywhere. We were tilted precariously to the left at a 25 degree angle.

Our crew got out and had a look.

"Fuck," said the normally-unflappable Mark, at which point we realized we were in serious deep doo-doo as such unprofessional comments never escaped his lips in front of us.

We all got out to have a look. It turned out not to be doo-doo at all, but a trench of gray, dense clay.

"This was a case of classic salt pan syndrome," explained Mark later. One Dragoman truck had once been stuck in a Bolivian salt pan for nine days, and Guerba was rumored to have once abandoned a truck altogether after attempting to mat out using their own seats. He also explained later that he had been angry when Duva had revealed that another overland truck had been stuck in that same spot a few weeks earlier. "Why didn't he tell me that earlier? We would have gone over the volcanic rocks."

But for now, Mark couldn't get angry as he had to deal with the

situation.

"I'm not inclined to rush into this," he said. "We're not getting out of here any time soon. Shall we have tea?"

So we pulled out the gas burner and the campstove and put a kettle on. Mark and Tony, both old hands at this sort of thing, discussed our options. Sam was experienced in bogs as well -- he'd been in Malawi in Nikki's six-day bog in '99.

Warning: 16-ton truck ahead

Warning: 16-ton truck ahead

Everyone drank tea and contemplated our sunken vehicle.

Dig it!

Dig it!

Finally, Mark, Tony, Sam, and Duva took shovels and disappeared under the truck. Charles enthusiastically went with them. Bits of clay started to fly out. The rest of us tried to help but it was pointless. Nathalie tried to make progress with a tiny garden shovel and gave up in disgust, saying "I might as well be using an emery board." I was on beverage duty, and had to make tea for those with clay-caked fingers.

Preliminary digging completed , we unlocked the sandmats. They were stuck under the tires. Mark started up the truck.

We sunk deeper. Mark cut off the engine.

Duva offered to run back to Kalacha to find a tractor to haul us out. It would be a two-hour run, but there were few options. He took water and set off, while I tried to amuse his sister's baby with a tennis ball. Others discussed the possibility of making clay pots with the free time. Mark flew his kite.

Mark flies a kite

Mark flies a kite

After an hour or so of sitting in the sun, I got bored and wandered off to a fringe of palms at the edge of the desert. I sat for a while and sang a song. Perhaps when I got back the tractor would be there.

It wasn't, although a few skinny local men had materialized out of nowhere to offer undesired advice. The group had tired of inactivity and cooked lunch. We had run out of fresh food a few days ago, so lunch was pasta surprise with a sauce made of canned meats and vegetables.

The wind was strong, making the real surprise in "pasta surprise" the coating of reddish dirt that I consumed without complaint.

Three hours after Duva left us, we were still sitting bored in the

middle of the desert.

"How long does it take to get a tractor?" we groused.

Finally, the crew got tired of waiting. We had to assume that Duva had encountered a setback. It was time to explore other options.

Mark instructed us to fetch rocks and wood to put under the tire, but in truth I think he just wanted to keep us occupied and out of harm's way while the crew completed its dangerous jacking operation.

"Discover the Dream"

"Discover the Dream"

PAZ was equipped with several jacks. Using blocks of wood and spare tires as jacking points, the guys were able to get the jacks under the truck and pump them up to try to lift the truck. The point

was to lift the truck and then put the debris in the clay trenches so

that we would be raising the left side inch by inch. In reality, all we managed to do was drive the jacking blocks deep into the clay.

Finally, after a lot of trial and error, they managed to slightly

raise the truck and unload rocks under the sunken wheels.

Just then, five hours after he'd left, Duva appeared on the horizon. In a tractor.

"Now remember," Mark reminded us. "We are glad to see him and not angry that he's been gone so long."

Marie and Monica

Marie and Monica

We were glad to see him for a minute. Then the tractor crew latched a steel cable onto PAZ's rear and pulled. The truck ended up deeper in the clay, at a more alarming angle than we'd been before our crew had started the jacking.

It was time for Plan B. Or C. I'd lost track.

Duva's sister keeps an eye out

Duva's sister keeps an eye out

The tractor went off to collect large stones to build a new road

underneath PAZ's wheels. Tony and Mark went back to work on the jacks, helped by Charles and Sam. The rest of us abandoned our dignity and cowered in a pack under the lunch table, which provided the sole square of shade in the entire desert.

The tractor returned with the stones and promptly got bogged in clay itself. I felt a surge of panic, but then the tractor driver used the bucket to lift the tractor up and out of the ground.

The jacks went up, the rocks and sandmats went down, and finally, after a bit more tea, the truck moved a few degrees closer to its natural state.

There was more digging, more jacks, and more rocks. I was still

preoccupied with cowering, and in spite of hiding from the sun, several of us got sunburned noses that took weeks to vanish.

above the point of departure

above the point of departure

Finally, ten hours and a lot of mud and tea later, PAZ triumphantly pulled out of the clay and back onto the salt. Mark later explained to me that the goal in a bog is to keep the truck above the "point of departure." A well-balanced Dragoman Mercedes has a much higher point of departure than an

overloaded cargo truck, a point proven to me with gusto a month later in an Isuzu in Ethiopia.

the aftermath

the aftermath

We returned to Kalacha for more pasta surprise. We were a lot more appreciative of the showers this time.

"A.W.A.," said Charles.

"What's that?" I asked.

"Africa Wins Again," he laughed.

KALACHA TO MARSABIT

OCTOBER 24

In a repeat of yesterday morning, we collected Duva, his sister, and his sister's baby to head off to Marsabit. But this time we made it. We drove over the volcanic rock route, and managed an uneventful morning. We arrived in Marsabit in time for lunch.

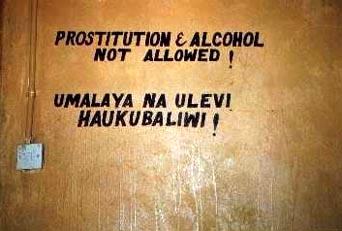

The "best" hotel in town didn't have room for us. We ended up next door at "Dikus Hotel," which turned out to be quite acceptable, with pit toilets and electric-heated showers at one end.

sign at the hotel door

sign at the hotel door

Monica and I went to hunt for chocolate and encountered a traffic jam of two bicycles and three goats. There was no launderette in Marsabit, and certainly no e-mail. It was a rinky-dink town, although it was a thriving metropolis compared to everywhere we'd been in the last few days.

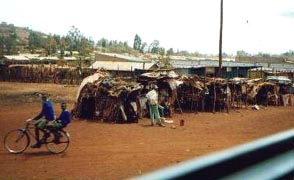

no internet cafe here

no internet cafe here

The supermarket didn't have chocolate and in fact, didn't have much of anything.

"Don't waste your time," said Sam, who went to the supermarket

first. "All it has is soap and cereal."

Of course we did anyway, right after a nice tailor sewed up the latest holes in my Columbia travel wear. I'd was beginning to look like the Patchwork Girl at this point.

We were starting to worry that perhaps there was no chocolate in Marsabit, but with some relief found a tiny shack that sold Cadbury's. A kid beside me at the counter said "give me money."

near Marsabit

near Marsabit

"Why should I?" I asked him.

He laughed and moved on.

Monica and I walked on, munching our "Fruit and Nut" bars. A group of children spotted us and took off running at us at breakneck speed.

"No," we called over. "We're EATING our candy." We'd earned it.

Giggling, the kids stopped and left us alone.

Standing outside a wooden soft drink-selling hut, we noticed an

attractive goat.

"You can take its photo," offered a shoe repair man.

"I don't want to have to pay it," I joked.

Slightly indignant, he explained to me that there are many poor people in Kenya, but that I surely would not have to pay the goat for its photo.

Embarrassed and humbled, I talked with the shoe repair guy for a

while. He was a nice fellow, who was just looking to converse and pass some time. It was a switch from chatting around tents with other passengers.

Monica and I drank our Cokes and moved on.

"I wonder where I can buy a newspaper," I mused aloud. We'd been out of touch for days, and rumor had dreadful things happening in Israel.

Two boys overheard me and proceeded to escort us from store to store, until we tracked down a copy of the weekly "East African."

Monica and I were thrilled with Marsabit. It was a crummy little

shithole, but its citizens were charming.

Later that night, Monica, Charles, and I walked to the town bar, which turned out to be several individual rooms strung together. The front one was empty. The second was crowded with locals watching a police thriller video, and the other rooms were all indistinguishable and seemed to stretch off in all directions.

We sat down in the empty front room and ordered soft drinks. In short order, we were joined by Mark, Tony, Sam and an older European whose job it was to escort trucks through the Kenyan frontier.

Sam later explained to us that when he came into the bar with Mark and Tony, two local men spoke to each other in Swahili.

"What is he doing with all those white people?" They muttered.

Sam said this happens to him frequently, causing him a lot of grief.

Charles left, while Mark talked to the European. Tony and I gossiped about ex-Dragoman drivers. Monica was probably bored but was polite enough to appear interested. A second later she was feigning much greater interest when the two local men invited themselves to join us. They even asked her to move so that they could sit down next to her, in spite of the rest of the chairs in the room being totally empty. They were sharing a beer between them.

"Why do the complete nutters always sit next to me?" said Monica in her thick Scottish accent. The two men smiled obliviously.

After they tried to work their way into our conversation several

times, I finally got tired of watching them struggle and tried to be

semi-polite.

"Where are you from?" They asked.

"She is from Scotland," I said, motioning at Monica before elaborating on the truth out of boredom. "I... am from Scotland too. And he is from England and so is he." I pointed to Tony and Sam. Sam was wearing an Oxford University sweatshirt.

The men looked surprised.

"You!? You are English?" They said to Sam.

"No," said Sam, looking at me sideways. Then my offhand comment got us into trouble.

"Why do you pretend to be English?" They asked Sam. "You are a black man."

Sam lost his temper.

"Do not call me that," he said. "You may call me Kenyan or you may call me African, but do not call me Black."

The subtleties of linguistic semantics were completely lost on the two locals.

"You should be proud of what you are," said the men. "Why are you embarrassed to be Black?"

"DO NOT call me Black," said Sam. "I am proud to be African."

The men argued some more, and then Sam said that he hadn't invited them to sit down, that they obviously just wanted to talk to Monica, and told them to piss off.

Tony was looking amused by this whole exchange. Mark was oblivious to it. Monica and I were watching the proceedings with interest.

The discussion degenerated into a heated argument, and the three slipped in and out of Swahili. Later, Sam told me that the men had said they'd had a gun. Sam had said, "fine, then shoot me," because he'd suspected they had no gun. He was right.

"PISS OFF," Sam said several times, always in English. There was

probably no Swahili equivalent.

Finally, tempers calmed and both sides agreed to not speak of the matter if the other did not. We all breathed a sigh of relief, until it started again a second later.

"You cannot tell me to piss off..." started one, and things began to heat up again.

I jumped into the fray now.

"You have all agreed to shut up. So shut up."

"Are you telling me to shut up?" said one of the indignant locals.

"No, you all agreed to shut up. So you shut up and you shut up and you shut up. Everyone shut up."

Everyone shut up, including Monica, Tony, Mark, and the European. We all stared at each other for a moment. Monica and I were desperately trying not to giggle. My inclusion of everyone in the "shut up" instructions meant that no one could speak.

"Right," said Mark, finally aware that something was wrong and that it was time to get out quickly. "It's time to go."

The European man piled us Drago-folks into the back of his truck and drove us back to the Dikus. Tony and Sam's room was next door to the one that Monica and I were sharing, and we could hear Sam ranting on late into the night.

MARSABIT TO MOYALE

OCTOBER 25

It was pouring rain when we left the Dikus, so we packed speedily for the trip to the border. We collected our armed guard and drove the last few hours of horrid road to the Kenyan town of Moyale, which is just opposite the much bigger Ethiopian town of Moyale.

In another moment of serendipity, I finished reading "Out of Africa" just as we left Kenya. I later saw the movie, and thought it made Karen Blixen look shrewish and dull. She appeared to be neither of these things from her writing.

We cleared Immigration in three hours. The Kenyan side was easy. They stamped us out, we drove across the border, and then waited in a line on the Ethiopian side.

After getting our passports stamped, there were two more lines to wait in. The first was to show our certificates of yellow fever vaccines, and the second was for Customs to look at our bags and take our currency declarations. And once the passengers were done, PAZ itself had to get through the border formalities. It was 5:30 p.m. before we cruised into Moyale, Ethiopia, marveling at the smooth, paved road.

"Youyouyou!" screamed the Ethiopian children when they saw us.

Unfortunately, there was no room at the inn. There was some sort of conference in town, and all the rooms were booked. We went up the road to Bekele Molla Hotel, which was also fully booked, but they had a few rooms that were in the process of being renovated. We could stay in those rooms if we didn't mind "roughing it."

They weren't horrible. Or actually, some of them weren't. Monica and I scored a room with running water, no bathroom door, and a lot of mosquitoes. But the door locked and the sheets were clean. I set up my mosquito net. Monica and I agreed to alert the other when we were in the bathroom.

Some of the others didn't fare so well. Tony's room was dreadful. He asked reception to clean it. They sent down a crew, but the crew just looked, laughed, and walked away. He slept in his swag, a tent with a built-in mattress and sleeping bag, instead.

After dinner around the truck, Mark gave us a primer on Ethiopia.

"When you hear the children scream YOUYOUYOU at you, it means nothing. They are just excited to see you, and it is the English equivalent of something not impolite in Amharic. So expect to hear it a lot, and don't be offended by it.

"The same goes for the word faranji. It means foreigner, and they use it to describe you. It is not meant as an insult.

"Ethiopia is a tough country to travel in, but it is also a rewarding

country. Some say that it is the India of Africa, so for those of you

that have been to India, that may mean something."

That meant something to me. I had found India difficult when I'd been there in '98.

"Also, Ethiopians are modest and conservative in dress. No short

shorts. Everyone must cover their shoulders at all times. Ladies, no

singlets and the bras have to go back on. Sorry.

"This next rule is somewhat embarrassing to mention, but it is a MAJOR rule here and you MUST obey it."

Mark paused, clearly relishing the moment.

"No farting," he said.

The guys laughed. The women were all relieved -- our truck had become too stinky lately, and the smelly noises were clearly coming from one or two sources, both of which happened to be male.

"Now I know at home some of you may fart in front of your friends and you all have a good laugh over it, but it simply isn't done here."

I later read in the guidebook that Ethiopians found public flatulence barbaric, and considered the Italians and the French the worst offenders. They claimed that the French were masters of the "silent but deadly" gas.

I also read in the book that Ethiopian women are expected to play hard to get, so often when they say "no" they mean "yes." We were not to be surprised if an Ethiopian man did not believe us when we told him we were not interested. If he did not get the point, we were to slap him -- twice, as once was bad luck. Fortunately, I didn't have to slap anyone while in Ethiopia, although I did have to outsmart a few would-be Romeos.

MOYALE TO MIDDLE OF NOWHERE

OCTOBER 26

We were introduced to Ethiopian bureaucracy at the bank. It took an hour and a half to change money, due to the mind-boggling amount of paperwork that was required for 13 people to change traveler's checks. There were additional formalities -- the security guard confiscated everyone's cigarettes, lighters, and pocket knives while we were inside.

As we drove north out of Moyale, I realized I'd been harboring a

grudge against Ethiopia.

My mom had an Eritrean foster daughter for a while. Sophie and her sister had escaped the war, traveling on camels across the desert to Sudan, where they'd promptly been arrested for wearing indecent

shorts that their uncle had sent them from the States. The 30-year

Eritrean Ethiopian War is a sensitive, emotional subject for Eritreans, and I'd been sympathetic to Eritrea at the unconscious expense of Ethiopia. Then, as we drove along the tarmac watching impoverished Ethiopians carrying plastic jugs of water on donkeys, I realized that the average Ethiopian had as much to do with the war as I did with "Operation: Desert Storm." That is to say, nothing.

The countryside turned to lush, green hills with a single band of

black asphalt cutting through and into the hills. Southwest Ethiopia was undergoing a famine, and this seemed unbelievable given our fertile surroundings. Apparently there is some sort of regional distribution system that leaves some areas without, while other areas have too much food.

Occasionally, small drab towns would pop up, their cement-block single room buildings open in front. People lined the roads, along with goats, donkeys, horses, and dogs. All used the road as well, as if it were their right and were not built for motor vehicles. Children chased our truck and screamed "YOUYOUYOUFARANJI" at the tops of their lungs. Every single one of them waved enthusiastically. We always waved back, and I wondered briefly if it

was possible to get carpal tunnel syndrome from repetitive waving.

I had not enjoyed being on the truck in Kenya. It had been dull,

suffocating, and claustrophobic. But suddenly, with the overwhelming possibilities of Ethiopian culture being full-on and in my face, I was pleased to have an experienced and appreciative guide. I was glad for the refuge of the truck and the group. When the going got tough, I wouldn't get tired and burn out on the challenges of Ethiopia. The truck trip would minimize the impact of the difficulties, making me able to appreciate the positive aspects of the country.

Mark discovered a smooth new road had been built at the turnoff for our hotel, and was pleased. He was not so pleased ten minutes later when he discovered that the hotel had been demolished to make room for the road.

"I don't know where there's another hotel," he cautioned us. "We might have to drive another three hours to Dila." It was already dark, and Ethiopia, with its goats and dogs and people, was not a good place to drive in the dark.

A few miles down the road, we stumbled onto a good hotel with a parking lot and secure, clean rooms for everyone. We all got our own rooms.

"In Ethiopia, you will find that most rooms are either singles or have double-beds. There are very few twin rooms, and backpackers traveling together is fairly new here," explained Mark. "So if you would all start hooking up, it would save us money."

He was joking, but we all eyed each other warily. There were no sparks whatsoever on this leg of the trip.

We cooked dinner in the parking lot. Sam and Mark were both concerned because the dish du jour was "bangers and mash." I had made it clear that I did not consider the British standard of mashed potatoes, baked beans, and sausage to be a proper dinner, and was touched that they ordered some Ethiopian food for the group and invited me to eat extra. I did, but I also dug out some of my instant soup. Have allergies, will travel with own food.

Sam, Mark, Charles and I stopped in the hotel bar for a nightcap. It looked like someone's parents' rec room. A few enthusiastic men were there, dancing alone, and a woman in a sleeveless evening gown stood at the bar. It was all rather depressing, so I went to sleep.

MIDDLE OF NOWHERE TO ADDIS ABABA

OCTOBER 27

There was no light at five a.m. in our nice hotel in the middle of

nowhere. And the water had been turned off as well. It helped us get

ready quickly, as we threw on clothing by candlelight.

We reached Shashamene, the rastafarian capital of Ethiopia, in mid-morning. Mark warned the group to be careful -- Shashamene had a xenophobic edge to it, and the last time he'd been here children had thrown rocks at the truck.

Instead of the steady refrain "YOUYOUYOU," I heard "FUCKFUCKFUCK" at least once, and it was clearly aimed in our direction. Mark devised a plan to keep the truck moving so it wouldn't be a target.

First, he dropped off the group at a cafe and told them to stay put. Then, he took Sam and a few shopping helpers to the outdoor food market, and left them there. Finally, he and Tony took me to the bus station so that I could catch a bus to Addis Ababa.

I was leaving the group for a few days. They were going to camp in the Bale Mountains. I was opting out of this excursion, because I needed to get to work on acquiring a visa for Sudan. Given the events of September 11, it wasn't altogether clear that the US Embassy in Addis Ababa would give me the recommendation letter I'd need to get the visa. It also seemed unlikely that the Sudan Embassy would give me the visa, even if the Americans agreed.

There's a civil war on in Sudan, and it seemed unlikely that the Sudanese would want to worry about a lone American tourist going sightseeing in addition to their other woes.

Additionally, I needed some time alone and some breathing room. I had recently learned to appreciate the bubble of westerners inside the truck, but I would still be happy to have a few days of space.

Tony managed to park the truck inside the bus station lot, which meant we were less likely to have rocks thrown at us. I walked towards the buses, calling out "ADDIS ADDIS" as I went. Friendly men pointed me in the right direction, towards a long, crowded bus.

I bought one of the last two "seats." In Ethiopia, the law is that

everyone must have a seat. Standing in the aisle is illegal. Once the

real seats are gone, little wooden stools take over. As a guest, I was not subjected to the little wooden stool. They cleared a seat for me on a metal box just behind the driver. My feet hung over the side, and my right side faced the bus. The entire bus had an excellent viewing stand, perfect for watching the strange activities of one blond faranji. As I bought my ticket, an old woman with cataracts butted her head into my hip repeatedly until I gave some change.

I went to report my success to Mark and Tony, who had drawn a crowd with their pale skin and weird vehicle.

I didn't know what to say to Mark. I felt guilty abandoning his trip. He was helpful, resourceful, and excellent at his job. I wanted to assure him that I could take care of myself, and to thank him for his efforts. Instead, I blathered "no problems, thank you." I was hopelessly inarticulate in from of the enormous audience that now stared intently at us. Mark, for his part, couldn't seem to stop cautioning me to be careful.

I rushed back to the bus, which had started up and was waiting on me to board. Distorted Ethiopian music came on the bus speakers. I shifted my butt on the hard metal case and we roared out of the bus park and the rock-throwing town of Shashamene.

With guilty relief, I spotted PAZ driving off into the distance --

without me. I was a solo traveler again.

Fifty Ethiopians and I turned to the opposite direction, on the road to Addis. Perched on the metal box behind the driver, I was in an excellent vantage point for viewing green Lake Langano. We sped through small towns brimming with chickens, goats, horse-drawn carts, and bicycles. I was excited about Ethiopia and couldn't wait to get to Addis.

Every time I looked back down the aisle of the bus, 50 people smiled and tried to get my attention. Friendly, challenging Ethiopia. I was going to like it here.

A toddler, Frances, sat behind me with his parents. I introduced him to the mangy stuffed Tasmanian Devil zipper-puller I had on my pack. He tugged on it. 50 passengers giggled. I pulled Taz's string, making him appear to move of his own accord. The kid looked confused, and the passengers howled with laughter.

Later, Frances' mom, laden down with baby gear, accidentally bumped me first in the butt and then in the head. The bus passengers went into hysterics. I had never felt so hilarious and had never had an audience that was so easily pleased.

The mom played patty-cake with Frances, and then sang him the months of the year, both in English and in Amharic. The kid sang along, pausing uncertainly at "December." He clapped, and they started again.

I thought back to the guidebook's warning about Ethiopian buses, and wished it had been wrong. Ethiopians refuse to open windows on buses. They think it will make them sick or something. So I was encountering this bit of irrationality firsthand, and it was damn hot (but at least in Ethiopia it wasn't polite to fart in public). I was lucky that the driver seemed to have overcome this bit of madness. At least he had his window open a crack.

I didn't mind the heat too much though. This afternoon I would be alone in a decent hotel, relishing my upcoming dinner at Addis

Ababa's "Burger Queen." Other bus passengers offered me snacks on the bus -- beans removed from a long pod. They weren't surprised when I declined.

I was used to the sounds of Swahili, and was now having to get used to not just a different language, but also a different alphabet.

The bus passed a dead man lying sprawled by the side of the road. He was naked from the waist down. The Ethiopians all looked at each other with concern, and at me with some embarrassment, but the bus roared on.

You can always sense a city long before you can see it. The traffic thickens, stores proliferate, and people seem to be rushing about. Addis was no different.

We soon approached the city proper, and I started hunting for

landmarks using the anemic map I'd hurriedly copied out of PAZ's "Lonely Planet" guidebook. I spotted the Sudanese Embassy, and when we reached a roundabout just up the road, I pointed to the right and queried "La Gare?" Several Ethiopian passengers enthusiastically nodded. Yes, that was the direction to the train station.

The bus stopped and let me out. A young man walking by pointed to a row of taxis.

"They can take you to where you need to go," he said.

I got in, negotiated a fare of 15 birr, and then proceeded to misunderstand and think I had negotiated a fare of 50 birr. The driver did not correct me. Later, I realized I had overpaid and thought perhaps ripping myself off was not such a good start to my time in Addis.

I checked into "Buffet de la Gare," a pleasant, $12 a night "en suite" hotel, unpacked my bags, and headed off to "Burger Queen."

NEXT: Will Marie get the Sudanese visa? A week alone in Addis, another dead man, and rejoining the group (this time with enthusiasm).