Addled in Addis

(Marie-mail #59)

ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA

OCTOBER 28

I awoke early to a sun-drenched room. Africa had changed my sleeping habits. In my previous life as a freelancer, I'd worked well into every night and never awoken before nine. But days began with sunrise in Africa, and if I wanted to go anywhere or get anything done, I had to adhere to the local schedule.

Breakfast was included with the price of my room at "Buffet de la Gare." I had come to expect a brown fried egg and greasy meat as my complimentary breakfast in most places, so I was pleased to get fresh-squeezed orange juice, three slices of thick toast, and delicious Ethiopian espresso.

Ethiopia has a credible claim to being the birthplace of coffee, and proudly produces rich, dark beans for local consumption as well as export. As a coffee snob, I had been on a lucky streak. Every country I'd visited in East Africa -- Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia -- had produced excellent, unique, java and shunned the typical traveler's staple, Nescafe.

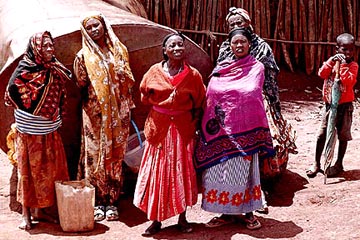

greetings from Moyale

greetings from Moyale

The actual "buffet" part of "Buffet de la Gare" was a hot nightspot, and the thumping bass of the band had gone on well into the night. The stale smell of tobacco was no doubt permanent in the restaurant, and competed with the coffee aroma.

After a quick shower, I wrestled with the toilet until realizing that I had to open up the back and fill the tank manually. But I didn't mind. I was excited to be on my own in Ethiopia.

It was Sunday, and banks were closed, so I took a 15 birr

taxi to the Hilton to change money and buy a guidebook. A farmer was herding his goats down the street in front of the Hilton, towards the UN African headquarters.

The sights were open, so I went first to the National Museum to see "Lucy," the oldest nearly-complete human remains found to date. Actually, the real remains are stored in a vault. The skeleton on display is a modern duplicate.

Then it was off to see Abyssinian lions, the rare black-maned Ethiopian lions. I got to the zoo just at feeding time, and watched with interest as children were invited close to the cub cages for personalized photos. The larger lions paced back and forth in their small cement cells, waiting for their lunch, until the keeper threw a hunk of raw meat at each of them. They all tore into it viciously, as if they hadn't eaten for weeks.

postcard of Abyssinian lions

postcard of Abyssinian lions

A taxi took me to the hip Piazza part of town, which was crowded with stores but still shabby. Everything there was closed on Sunday, except for Tomoco Coffee. I bought a kilo of Ethiopia's finest to drink when I got back on the Dragoman truck. A nice man helped me pick out some beans. It was lunchtime, so I asked him if there was a good restaurant nearby.

"When will I learn?" I thought later. Mention what you need and not only will someone help you, they will join you and corner you and suddenly your day has become their own personal property.

The man described a lunch place, and then offered to show me the way. It was a new country for me, and I was trying to be optimistic instead of cynical. It was entirely possible the man was just being polite.

He escorted me to the cafe and invited himself to join me.

"Do you mind if I sit down too?" I knew full well the protocol of the situation. In Ethiopia, the host pays for lunch, and apparently I was the host here. Chafing inwardly, I graciously indicated he could join me.

"Where are you staying?" he asked.

"Bel Air," I replied easily. Lying about my hotel, room number, or amount of money in my pocket was second nature to me by now. The Bel Air embellishment wasn't a total lie. I'd stay there later in the week with Dragoman.

"What is your job at home?" asked the man.

"Artist," I said. His eyes opened in apparent astonishment.

"I am also an artist," he declared.

That surprised me, but wouldn't have further south. In Tanzania and Zimbabwe, everyone was an artist. They made tourist art -- sturdy elephant bookends, six-foot wooden giraffes, and whatnot. But here in Ethiopia, where tourism was not even yet in its infancy, I thought that perhaps my new friend was a fine artist.

He dashed my hopes quickly, by pulling out a photo of one of his "designs." It looked like a factory-produced batik of a nomad, not unlike hundreds I had seen further south.

He was too anxious, in the end, as he desperately tried to convince me to come to his gallery. It wasn't enough to give me directions ("on the Burger Queen Road between Shell and Mobil") and tell me when the gallery was open. He wanted to pick me up and escort me. I made excuses. He promised to call me at the Bel Air. I felt a little bad about having lied to him but I certainly didn't want to be forced to go to his studio to "ohh" and "ahh" over art I didn't even like.

I paid the bill for both our meals and he put me in a taxi, instructing the driver to take me to the Bel Air. That was problematic. I waited until the driver turned the corner, and then told him to stop and let me out.

Alone again, I wandered down the main street, past the coffin shops, and stopped into a souvenir store. A British woman sat in the dark, examining an antique metal crucifix by candlelight.

"Oh," I said. "Has the power gone out?"

"You haven't been in Addis very long, have you?" She laughed.

I shopped by Maglite, realizing that Ethiopia had amazing religious art. In spite of my lack of religious faith, I knew good art when I saw it. On display were intricate carved wooden doors on hinges that opened to reveal colorful biblical paintings below, as well as silver seals, crucifixes, and sequential painted stories on canvas.

After buying a few things, I was happily talking down Churchill Avenue, slowly heading back towards my hotel. A jittery Ethiopian teenager took up step beside me and started speaking French to me.

"Je ne parle pas de Francais," I said.

"I know," he replied and he started talking about his favorite movies.

He was a nice kid, and his imitations of all his favorite movie stars charmed me. He showed me how Wolverine's claws shot out in the "X-Men" movie, and I didn't bother trying to explain to him that I was not only intimately acquainted with Wolverine, I knew decidedly geeky details about all his friends, enemies, and past creators as well.

The kid lost me with his next comment. He told me with great conviction that he did not believe that Jackie Chan had died in the World Trade Center attacks. Uh, yeah, right... I let it go.

He took me from photo shop to photo shop, trying to find a place that could repair my broken point-and-shoot. I had smacked the camera against something, and it would never work again unless Canon got their hands on it.

I was starting to think that maybe the kid was just nice, when he doubled over in apparent pain.

"Yeah, right..." I thought, but obligingly said, "are you okay?"

"I am just feeling very sick, because I have not eaten in a long time," he explained.

It was an awkward situation. The kid was obviously homeless, and probably a glue-sniffer, but he needed food. I didn't think he should be pretending to be so sick in front of me, but he couldn't very well just ask me for money. I felt bad, and gave him some money, even as I wondered if he would really eat with it or if he was abusing glue as so many children of the streets do.

Ethiopia is the world's third-poorest country, and many people there are destitute. Mark had told us, in his lecture on our night in Moyale, that we should not be afraid to give to beggars in Ethiopia.

"You won't be ruining it for other tourists. Even the local people give to beggars, so just follow their example and give a few coins here and there. Don't give a lot, or tourists will become a target. And you can't give to everyone, so try to pick a cause."

I had chosen crippled women and destitute children, but rapidly found myself giving to anyone who was disabled as well.

I managed to ditch my escort by taking a taxi back to my hotel. Later, I left to find dinner and passed a couple and their little girl walking outside the train station.

The little girl was around six year old, and was dressed in her frilly pink Sunday best satin dress. Her parents each held one of her hands, but when she saw me, she slowly, deliberately removed her right hand from her mother's. She stuck it out to me, smiling. I shook it and her eyes lit up. Her parents beamed their approval.

A taxi driver offered to drive me to dinner, and after some discussion we decided that I should eat Indian food.

"I'll take you to Sangam," declared the driver. I agreed, as it had received positive write-ups in both the guidebook and in "TimeOut Addis."

I ordered samosas, vegetable curry, a mango lassi, and naan, and sat back to watch "BBC World" by candlelight. I was content.

OCTOBER 29

Plan A was to forge ahead through Sudan. Plan B, in case I didn't manage to get a Sudanese visa, was to take the train to Djibouti and catch a ship from there.

But there was no apparent schedule, and the only railway employee I could find gave me a vague approximation of when the train might leave. He shoved me away as the train from the coast arrived, and I caught a taxi to the Embassy of Sudan.

"Christian or Muslim?" asked the apparently Christian taxi driver once we were underway.

"Neither," I replied.

"What?" he was confused. In his experience, one was always either Christian or Muslim.

"No religion," I said firmly. Quickly, knowing he wouldn't catch it, I added "Iamagodlessheathen."

The taxi driver contemplated me, and then declared the Muslims were to blame for the state of the world. I shrugged. I didn't approve of the polarization going on in the world, and wanted no part of it.

I nervously left the taxi and tapped on the metal gate in the wall at the Sudanese embassy. An Ethiopian guard poked his head out and let me in.

"Sign in," he said, pointing to a book. He took my passport.

"U.S.A. Great!" he exclaimed. I felt a little bravado, but was mostly scared that I'd be turned down flat. I'd heard the Sudan embassy required letters of recommendation from the applicant's home embassy. I'd also heard that the U.S. Embassy did not issue recommendations.

"Where's the visa section?" I asked the guard.

"See that pickup truck? Go in the door next to it."

I walked, jittery, across the parking lot, and entered a dark room.

A Sudanese man with white hair said, "why do you want to go to Sudan?"

"Transit to Egypt," I responded.

Bzzzt... wrong answer. He looked at me disapprovingly.

"Why not just fly to Cairo?"

I explained my mission.

"I want to go through Sudan. But maybe this is a problem," I said, sliding my passport across the desk to him.

He looked furious.

"You hate us," he said.

"I personally don't hate anyone," I started, but he cut me off.

"I know, I know. I don't mean the people. I mean America."

I changed the subject.

"I want to see the pyramids at Meroe. Do you know them?"

"Look behind you."

The pyramids of Sudan adorned a calendar on the wall.

"Why don't you apply for a tourist visa?" he suggested. I crossed out "transit" on my application and wrote in "tourist."

"Two photos and sixty dollars."

I forked it over, while he muttered that the U.S.A. hates Muslims.

"I personally... " I began.

"I know, I know," he grumbled. "They think we are all terrorists."

"That's why I want to go, to show it's safe." I had found an angle.

He smiled, gave me a claim check, and told me to telephone on Wednesday at noon. I had been warned to follow his instructions precisely, by Australian writer Peter Moore who had to work a lot harder at his visa application than I had to. I left, reminding myself to call precisely at noon on Wednesday. Perhaps I'd get to see the pyramids at Meroe after all.

I went to the Blue Nile Hotel, where I'd spotted an "internet cafe" sign. Could it be?

It was. And Claudine, one of the Dragoman passengers who'd left our group back in Maralal, was sitting at one of the terminals.

We went for tea, and later Claudine went to the health clinic with me.

Back in July, concurrent with my second rabies vaccine in Berlin, I'd developed a cyst on my arm. In Nairobi, a doctor had told me to "keep an eye on it." I had, and now it had swollen to become a big, red lump.

In true international medical style, I was moved from waiting room to waiting room. Just as I'd begun to despair of seeing a doctor, a nurse would call my name. But no, she wasn't taking me to see the doctor, just moving me to a new room.

Finally, I was in the doctor's room. She basically said the same thing that the Nairobi doctor had said.

"Keep an eye on it. I doubt it's related to the rabies vaccine. It's probably coincidence."

She told me to quit picking at it and prescribed an antibiotic ointment that shrunk it back to a reasonable size.

OCTOBER 30

Claudine had left her hotel and moved to Buffet de la Gare with me. She'd been harassed by the help at her last hotel.

She only fared slightly better in her new digs. The night clerk took a liking to her and took to phoning her in the middle of the night to declare his devotion. She was an attractive young woman, obviously used to fending off amorous would-be suitors. She managed to deflect the night cler, but he still regularly declared his love whenever the opportunity arose.

We both went to the Hilton for a nerve-wracking hair session in their salon. Claudine had a trim while I st in a chair with some Revlon product on my head.

"Revlon?" I said, aghast when the colorist told me what was stinging my scalp.

He looked confused when I told him the owner of Revlon had stripmined my company and left it for dead. The colorist wasn't real up on the latest news in comic book company financing, so he smiled blithely and stuck a German fastion magazine in my hand.

Later, Claudine and I tried to go to the UN headquarters to see a famous stained-glass window in Africa Hall. Unfortunately, Africa Hall was off-limits to tourists for the foreseeable future as heightened security had taken effect after September 11.

Claudine left me after a meal at the post "La Notre" cafe, and I sat in the internet cafe for a while. When I left to walk back to the Buffet de la Gare, I passed another dead man, sprawled in a crucifix position. His shirt was missing and his ankles bound. A policeman had just arrived on the scene, and was just getting off his motorbike with a pad of paper. I hurried by.

The dead guy and policeman were both gone the next time I walked by.

OCTOBER 31

It was a bad morning.

I was starting to crack a bit under pressure. Fascinating Ethiopia, with is anonymous dead men, begging cripples, and glue-sniffing streetchildren, was taking its toll on me. I was tired of seeing maimed people crawling on all fours, flip-flops on their hands as well as their feet. I was frustrated with the pace of progress on my own work -- the internet was so slow in Ethiopia, I could've just typed in zeros and ones instead of hitting enter.

And I was nervous. Today was the day that would determine my immediate future. If I got a Sudanese visa, I'd be set. If not, I'd have to take a train to Djibouti and hope my cargo ship agent, Christina Horn, could find me a ship. And it was the wrong time of the month.

Nevertheless, in the face of inconvenience, I didn't crack instantly. But shortly, I fell to pieces over nothing.

I had a bag of stuff to send home, including the religious souvenirs I'd bought in Ethiopia, my broken Canon point and shoot, an enormous Kenyan blond wooden hippo, and a marble egg with a map of the world painted on it. I had carefully used up the last of my packing tape and bubble wrap (note to travelers to East Africa: carry bubble wrap). I got up early and went to the post office.

The security guards -- there are security guards at all Ethiopian government offices and most respectable businesses as well -- inspected my bag. They were just about to let me in when one of them held up the Canon, barely visible through its protective bubble wrap.

"Camera," the guard announced, confiscating it and giving me a claim check.

"No," I explained, grabbing it back. "I'm posting that."

The guards stared at me. They spoke no English aside from "camera," and they didn't know what I was talking about.

I mimed a flying plane with my hand and put my camera on it. "United States," I said. "Canon, warranty."

They still wouldn't let me go. I was astonished and starting to slowly boil. The camera was broken, unreachable in its bubble wrap, and why on earth wouldn't they let me in the the post office with a camera anyway? Were they afriad I'd photograph their stamp collections?

Annoyed, I stalked off. A few minutes later, I was encountering more frustration at the other entrance.

"But the camera is broken," I said. I put it on the ground and motioned stomping on it. "I must sent to America."

The guard grasped my plan and understood my dilemma. He took the camera, in bubble wrap, and escorted me to the parcel counter. He showed the camera to the clerk and explained the situation.

"NO," said the clerk, pushing the camera aside.

The guard tried again, and was sternly spoken to. He apologized and left with the camera. I could retrieve it at the gate.

I was finding the situation ludicrous. I was going to have to carry a broken camera for a month (to Egypt), because of the arbitrary and illogical rules of the Ethiopian postal system.

I handed over the rest of my parcel. The clerk went through and pulled out my souvenirs.

"Permit," he said. "You must get permit."

I knew permits were required to export antiques out of Ethiopia, but my souvenirs were all brand-new, designed to look antique-like. They were obviously not state treasures.

"These are new," I argued. "They cast just a few dollars. Do you think I could get an antique for two dollars?"

He didn't care. He was erring on the extreme side of caution.

"Fine. Where do I get a permit?" I asked in an exasperated tone.

"Department of Antiquities."

"Where's that?" I expected it to be the next counter, or perhaps upstairs.

"National Museum," he said. I stared in disbelief. That was the other end of town. Was I really required to taxi across town, go through an in-triplicate paperwork process of certifying that my new souvenirs were not antique, then taxi back, check my camera, and wait in line again?

Apparently, yes. He dismissed me.

I could feel tears of frustration welling up, and subdued them. I marched down the street to DHL, where they told me I could mail all but the hippo (including the camera) for $100.

$100! That was an excessive price to pay for the paranoia of the Ethiopian postal system. And I couldn't carry this massive hippo through Sudan, where I'd be traveling in the backs of trucks.�

Now thoroughly depressed, I caught a taxi to the National Museum. I knew the going rate was 10 birr within town, and 15 for tourists. I was preoccupied with my mailing problem so I didn't state the fare clearly.

The driver took the longest possible route and then declared "30,000" when we pulled up to the Department of Antiquities.

curious kids

curious kids

This was the last straw for me. My tolerance for other cultures did not extend to illogical official rules and thieving. The taxi driver and I had a shouting match that ended with me throwing the 30 birr at him. Later, with Monica, I hit upon (and used) the idea of not negotiating. We'd get out first (that's the key), and then hand back the correct fare through the window. We could then walk off no matter what the driver yelled after us.

Teary-eyed, I took my wooden hippo and souvenirs into the Department of Antiquities.

"What is the matter, madam?" said the young man who worked there.

"Fight with taxi driver," I said, not feeling it was appropriate to say "your country has some stupid laws and everything in Addis driving me bananas."

He surveyed my souvenirs, and told me to take them all out of their bubble wrap, even though you could see everything clearly through the bugbble wrap. He started to tear into them.

"No," I shrieked in horror. I carefully peeled off the bubble wrap. "I need that to post with."

He examined every item and filled out a form for each one. He got to the hippo.

"What is this?" he asked.

"Hippo," I said. (Duh.)

"Unwrap it." I did, and its back leg splintered into pieces and collapsed. The wooden hippo had seen better days.

"Where did you get this?"

"Kenya."

"I cannot give you a permit for something you got in Kenya," he declared.

"I can't mail it without a permit, but I can't get a permit?" I asked in disbelief.������

"Right," he said, a bit sheepishly. He wouldn't give me a permit for a few other things that were obviously Kenyan, but when he got to my smaller wooden hippos, I just claimed they were Ethiopian.

The forms were stamped by an official -- in triplicate -- who apologetically said "it is not our rule. I am sorry."

The kid took it upon himself to "help" me. He told a taxi driver to take me back to the post office for 10,000 and then jumped in the front eat.

"I will help you," he declared. The warning bells in my head sounded loudly.

"No, I can do it alone," I said. "Honest."

"No, I help," he repeated. And that was the end of it.

We went to the post office, where they informed me that the mailing of my parcel -- seamail, minus the hippo, camera, and Kenyan souvenirs -- would cost $40.

"It is foreigner-price," explained my helper. "Can I mail it?" he asked the clerk.

The clerk sternly told the kid no, and I decided to go with DHL. They'd take the camera and the Kenyan souvenirs. The splintered hippo and I would have to part ways, as his weight would have put me into the next cost category, and I wasn't convinced the owner of the MariesWorldTour.com server would want a damaged hippo.

The kid asked me for a 10 birr tip for "helping" me. I reluctantly gave it to him -- the taxi had cost more than the already-inflated tourist fare. I thought back on Peter Moore's comments about Ethiopia. "Everyone had his hand out," he'd written.

I couldn't wait for the cocoon-like Dragoman truck to show up, to insulate me and rescue me from frustration.

And they were almost here. Claudine and I were to meet them at the Bel Air after lunch. But first, there was the small matter of my Sudanese visa. I called the embassy.

"Your visa is ready," said an official. "Come by now."

Claudine and I checked out of Buffet de la Gare, put our bags in a taxi, and rushed to the Embassy of Sudan.

Wordlessly, a well-dressed man pushed my passport across a desk at me. The visa was there, on page 35. Valid for one month.

"Thank you," I said, delighted. The gray-haired man walked in and I thanked him too. I scampered out, anxious to get back to my taxi before they changed their minds.

My earlier tears and frustration had turned to elation. We drove to the Bel Air, where Monica let me put my stuff in her room.

Triumphantly, I went to report to Mark.

"I got it!" I said, shoving my passport in front of him. The terrors of the Ethiopian postal system and the Department of Antiquities were suddenly a million miles away. Mark was as surprised as I was. No one had expected me to get the visa.

The group was, in light of the week I'd just spent alone, highly desirable and I was thrilled to see them. We all went for coffee at La Notre.

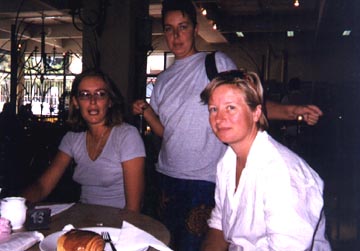

Claudine, Nathalie, and Letty

Claudine, Nathalie, and Letty

I spent the rest of the day, and indeed the next few weeks, as an appreciative social animal. Later that night, I even attended a group meal, although Claudine, Monica, and I left early to return to the Bel Air.

The Bel Air, we'd been warned, doubled as a brothel. Many Ethiopian hotels did, and there was no shame in it. We could hear people partying well into the night. Once, we could hear Sam arguing with the bartender, but mostly we heard Ethiopians yelling at each other in the parking lot.

Our actual room was disgusting, by far one of my top five grossest rooms of all time. It was rundown, with mirrors by the beds, and the mattresses had seen better days -- but a lot of rooms I'd stayed in had been shabby. No, the real revolting part of the Bel Air room was the bathroom. It stunk of a permanently backed-up drain, there was no toilet seat, and condom wrappers were permanently stuck in the bowl. They never disappeared, no matter how many times I flushed, and I wasn't about to fish them out.

Later, when Monica and Claudine returned to Addis after I'd gone off to Sudan, they stayed at Buffet de la Gare and took five others from the group with them.

NOVEMBER 1

I finally sent out my DHL package, happy to part with the $100. We spent the day at the market, where a department store gave me further evidence of the madness of Ethiopia. They threatened to confiscate my camera, as I should obviously not carry a camera into a department store. Why? Who knows? Maybe someone once hid a bomb in a camera, or maybe photos had once been used by the government against the citizens. Ethiopia's recent history had been rocky, and a certain amount of paranoia was probably justified.

At night, Monica and I, along with Dragoman newcomers Trevor and Heinrich, went to see Azmari Beat at the Ethiopian-French Alliance. It looked like the richest and most beautiful of Addis society were out for the evening, snacking on injera and tibs, and admiring the talents of "Mimi's Band."

Azmari Beat involves both traditional music and comedy. We unfortunately couldn't understand the comedy, but clearly something clever was said as everyone laughed appreciably. The music can only be described as surely being the source of the Xena: Warrior Princess war cry. "Ay-ya-yayaya," wailed the singers, while the musicians tapped out accompanying rhythms. The women danced too, jerking their shoulders back and forth in a way that looked shockingly non-PG for modest Ethiopia. We stared in awe, or maybe we were under the influence of the tej the group had ordered. Tej is a sickenly sweet honey-like wine, which finished by no one at our table.

We left early and caught a taxi to Castelli's, a fantastic Italian restaurant in the Piazza. It was some of the best food I had all year.

NOVEMBER 2

At last we were leaving the chaotic, challenging city of Addis and the foul Bel Air Hotel. I couldn't wait. I had seen enough maimed donkeys wandering through traffic, enough limbless tragedy, and had enough of fighting with taxi drivers.

Faye, Arthur, and Francesca joined us in addition to Trevor and Heinrich. Interestingly, Faye kept her backpack covered with plastic, and kept her sleeping bag in bubble wrap.

We passed beggars, commuters and runners on our way out of the city. Running is a national pastime in Ethiopia, and they even hold marathons occasionally.

At last, we were out in the countryside and on our way to the source of the Nile and the Blue Nile Falls. And I had learned my lesson and valued my friends, and was grateful for the presence of guides and a truck.

NEXT: Denial ain't just a river in Egypt, it's in Ethiopia too! Or at least its source is. Dejen, Bahir Dar, and the ancient city of Gonder.