Where the Pavement Ends

(Marie-mail #57)

NAIROBI TO NYAHARURU

OCTOBER 14

At the crack of dawn, I was awake and packing my bags. My neighbor, I could hear, was just getting in from one of Nairobi's late-night raves.

My Sunday morning breakfast included its usual 250 mg of Larium, and I headed over to "Lazard" internet cafe. The staff laughed to have me there so early. They were used to seeing me close the place down at night. The tech guy came over in his bicycle helmet to say "good morning." He knew a fellow computer geek when he saw one. I wondered what my taxi driver would think when he waited outside for me at night and I didn't appear. "She's headed north towards Ethiopia" would doubtless not be his immediate thought.

I had seen families living on the sidewalk in Nairobi. One deranged woman had worn only a plastic bag, and a see-through bag at that. I had also seen hip coffee shops inhabited by trendy youths with money to burn, and expat shopping centers surrounded by barbed wire. Nairobi's inhabitants, like its extreme economy, were bipolar. I had met open, giving, and friendly Kenyans in Nairobi. I had also encountered some of its most thieving and destitute. The schizophrenic populations matched the statistical gap between rich and poor.

For days, taxi drivers outside my hotel had been asking hopefully if I needed a taxi. Every morning I shook my head no.

I was perplexed when no one offered me a ride this morning. They'd gotten tried of rejection. I stared at the drivers.

"Taxi?" asked one finally, after staring back for a minute.

"Yes," I replied. "Take me to the Peugeots to Nakuru."

"Nakuru? You want to go to Nakuru?"

"Yes."

He asked his friend a few questions in Swahili. They motioned in response, clearly explaining the location of the Nakuru transport.

There are three ways of navigating Kenya's roads by public transport. One was by bus, two was by matatu (or "Nissan"), and three was by Peugeot shared taxi. The Peugeots were the most expensive option, in addition to being the most comfortable and fastest.

"Pehjet or Neeson?" asked the taxi driver. He had not understood my request for a Peugeot.

"Pehjet," I responded. This time he got it.

We drove to Cross Road, the bumpy frontier-like dirt road where I'd caught the "Busscar" to Uganda. The driver left me at "Cross Road Travel," and I put my bag into a "Nakuru" signed Peugeot. A man escorted me to the ticket window.

"This is my friend," declared the man. The ticket seller laughed and sold me a seat for 300 shillings. He took me back to the Peugeot and motioned me into the front passenger seat -- the best seat in the car.

I sat there for an hour, while the driver washed the car and waited for the seven seats to fill up. We left just before 9:30. I was meeting my group at 11:30 at Nakuru's "Midland Hotel" and was a bit concerned.

But I needn't have worried. We drove quickly, passing baboons and trucks, and pulled into Nakuru at 11:40. The Dragoman truck showed up ten minutes after I did.

The nine passengers had done a lot of moving in, and I had to shoehorn my way into the "already in progress" group. Everyone had staked his claim on the overhead netting and a seat, and no one moved to accommodate the latecomer.

"Why on earth did I think I could deal with an organized trip?" I asked myself. The preponderance of evidence suggested that I was deficient in cooperative group spirit.

does the water really go the other way?

does the water really go the other way?

We left Nakuru, stopping at the equator for a

water-draining-the-wrong-way demonstration. Our drive ended at Thomson's Falls in Nyahuru, where I assembled my little blue tent to the mockery of all.

"That's yours?" said Mark. "I thought it was a children's tent."

I had a Coke with the group, and met Sammy the Kenyan cook. He turned out to have worked with my friend Nikki for months. He'd even been on her famous bogged truck in Malawi. They'd gotten stuck in the mud for six days and had to rebuild the road to get out. She'd come down with malaria and salmonella immediately after and had to be sent home to England.

Sam could cook, I learned in short order. He did well with limited resources. I could potentially gain weight over the next month and a half.

I hiked down to the Falls with Trigger and Peter. "They are pretty falls rather than spectacular," read the Dragoman trip notes. The

walk back up the gorge, however, was spectacularly painful.

Thomson's Falls

Thomson's Falls

Later, the group went to the bar. I opted out, feeling claustrophobic already. After a cold shower in a dirty shack, I retired to the solitary privacy of my little blue tent. I curled up in my sleeping bag and Polar Tec sleepsheet, on my Thermarest, and read by carefully monitored candlelight (do not try this at home in your own little blue tent). I fell asleep to the sound of crickets, the falls, and a distant humming generator.

NYAHURURU TO SAMBURU NATIONAL PARK

OCTOBER 15

I sat in the truck in what may as well have been my assigned seat (the worst one), and read the Sunday "Nation" newspaper as we left Nyahururu.

The front page featured a big photo of an injured Afghani child. Inside, stories talked about anti-US demonstrations in Nairobi and around the world. In Indonesia, German tourists in Lombok had been assaulted after being mistaken for Americans. And down in the corner was an ad -- "study in the USA!" I had to laugh at the idiosyncratic world.

Back in August, I'd discovered that overland trucks dominate tourist Africa. I'd learned to despise commercial overlanding, whereas before, after Dragoman trips in Central America and the Middle East, I'd been a proponent. Overland trucks, with their camping gear and kitchen equipment, were self-contained little worlds. They're a good way to see a region on a limited time budget, and in cases where there is no public transport they're the only way.

But for the independent traveler, overland trucks are a nightmare. They'd dominated campsites I'd been at and often their passengers seemed hell-bent on partying ferociously into the night.

I'd researched northern Kenya and Ethiopia back in New York and had realized that 1)only by hitching on a cattle truck or going on an organized tour would I get through northern Kenya and 2)Ethiopia was going to try my patience. Dragoman was one of only a few groups that headed into Ethiopia. That suited me, so I'd signed up. Dragoman is one of the best, most expensive overland companies, so its clientele should be self-selecting, and I'd hoped the type of passenger who'd choose to tour Ethiopia would be more mature and discerning than the passengers I'd seen partying all night at "Shoestring's" in Vic Falls.

To an extent, I was right. The group was older than the groups I'd crossed paths with in Southern Africa. Unfortunately, most of them had been together for some time and routines and roles already had developed.

We crossed through the small town of Isiolo, the last outpost of paved road, internet access, and chocolate until Ethiopia, in two weeks time. From here on in, the roads would be dusty, potholed, and uncomfortable. I could have, I mused, gotten this far on my own, but after this I would have had to stick my thumb out to stop a cattle truck.

Isiolo, where the pavement ends

Isiolo, where the pavement ends

We drove to Samburu National Park, stopping en route at a Samburu village long enough to say "we'll be back tomorrow." The women of the tribe raced over to greet us with "Marky, Marky!" This was the first clue we'd get as to how popular our leader was in East Africa.

The drive took us into a hot game reserve, and we looked at animals on the way to our campsite by Samburu Lodge.

special enhanced zebra

special enhanced zebra

The most interesting animal was Grevy's zebra, a special, psychedelic, enhanced zebra found only in this region.

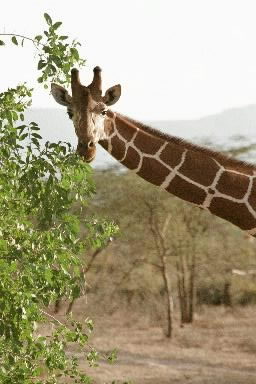

Other than that, we saw a few giraffe and some dik-dik, the chihuahua-sized antelopes that travel in pairs.

Samburu giraffes are different too

Samburu giraffes are different too

After setting up our tents, we headed over to Samburu Lodge to watch leopard-baiting. The lodge hangs a piece of meat in a clearing every night, and sometimes a leopard comes to have it as a snack.

crocs visit Samburu Lodge for the free food

crocs visit Samburu Lodge for the free food

But not tonight. The leopard must not have been hungry. He stayed away, and we walked back to camp, accompanied by an alert ranger with a gun.

The wind came up while we were sleeping and when it calmed down, I heard an animal outside my tent. It walked, stopped, and walked and sniffed.

"I'm going to be eaten by a lion," I thought. "My tent is too light and doesn't smell of canvas. The lion will smell me!"

Finally, the lion went away. I didn't get a lot of sleep.

SAMBURU NATIONAL PARK TO SAMBURU CULTURAL CENTER

NOVEMBER 16

I looked down at the tracks outside my tent. They were tiny and round. I appeared to have been terrorized not by a lion but by a dik-dik.

"It was a killer dik-dik," I declared defensively.

We went off on an early morning game drive. Our efforts netted only two oryx, one coreybuster bird, three giraffes, and a lot of dust. I fell asleep, having been kept up half the night by the vicious dik-dik.

tough to be a toddler

tough to be a toddler

We stopped back at camp in late morning, for a very British breakfast of beans, toast, eggs, tomato, and bacon. I had learned to despise fried eggs in Africa, and have no fondness for beans on toast,

so I stuck to my usual instant oatmeal and coffee.

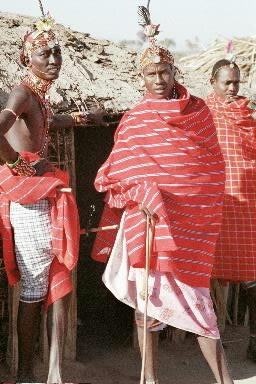

We took down our tents and headed back to the Samburu Village we'd stopped at briefly the day before. The Samburu are a nomadic herdspeople living in northern Kenya. They have stretched earlobes, jump when dancing, and wear blankets like their distant relatives the Masai, but they lean more towards glamour. The Samburu like to color their hair and wear more vibrant jewelry, or even feathers.

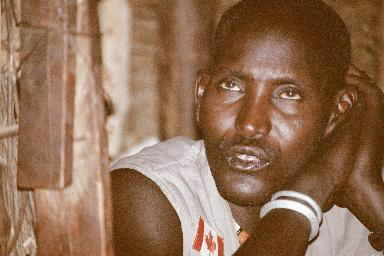

We set up camp at the village campsite and Steven, the tribal chief, came to visit.

He was the penultimate hybrid. His earlobes were stretched and pierced in the Samburu (and Masai) tradition. He wore a tribal blanket around his waist. His shirt was a khaki safari vest, embroidered with

Canadian flags. He was drinking a can of beer as he greeted us.

Chief Steven

Chief Steven

"That's nothing," laughed Mark later. "He used to show up in these glittery millennium sunglasses that were shaped like a big 2000."

Steven was authentic. He was the true-life real-world hybrid tribesman, a conglomeration of his nomadic lifestyle and the MTV generation. He lived in a hut with no running water or electricity, but he had millennium sunglasses.

Mark told us a story of how his groups used to visit another nomadic tribe. The tourists were always disappointed by the Gap-like apparel of the tribespeople, so the nomads had taken to changing into

traditional clothing exclusively for the tourists.

"It got to the point where I was calling ahead to say, take off your shorts and t-shirts because I'm bringing tourists by," said Mark.

Fortunately, Dragoman had located Steven's Samburu village. The village women had organized this cultural center, where they ran a campsite and invited tourists to observe their lifestyles. They were a proud tribe, and had not wholly adopted western ways. What they had adopted had been incorporated into their lifestyle but had not co-opted it. And they ran their cultural center with pride and efficiency, not the haphazard money-grubbing desperation I'd seen in earlier tribal visits.

Steven brought us some bad news.

"You cannot see our village today. All the women have gone to a funeral."

There was no arguing with his flawless logic, so we scheduled our visit for early the next morning and spent the day lazing by the river.

"Is it safe to swim here?" we asked Steven.

"Yes, but there are crocodiles."

"Many crocodiles?"

"Yes."

No one went swimming. And it was a good thing. The next morning we discovered that a lot of the proceeds from the village visits funded the schooling of orphans who have lost their parents to malaria

-- or crocodiles.

Bored with the lazy afternoon, I wondered what had possessed me to think I could take a truck trip. I was hostage to the whims of others. I wanted to do my laundry, but that required borrowing someone's truck key, finding a washbowl in the plastic bins, unpacking theluggage locker, pulling out my clothes and repacking the luggage locker. Showering also required unpacking the luggage locker as did putting up my tent for a nap. Perhaps I could just read my book -- if it weren't locked in the truck, along with my water. Now I remembered that I hated traveling this way. And I'd signed up for weeks of it.

Samburu warriors

Samburu warriors

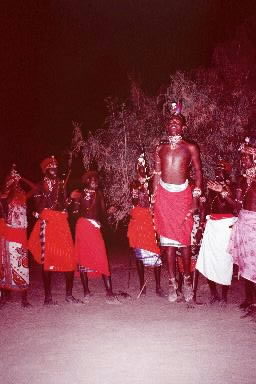

Later that night, the Samburu came by to show us traditional song and dance around the campfire. They all shook our hands heartily and accepted beer and cigarettes, but not our strange food.

warrior dance

warrior dance

As they danced, Steven gave us a blow-by-blow interpretation of each song.

"This is the welcome song," he'd say, or "this is the marriage song." They all seemed to consist of humming and chanting accented by men jumping or by women jerking their shoulders in a startling manner. The young women danced and the older women chanted, in between swigs of beer.

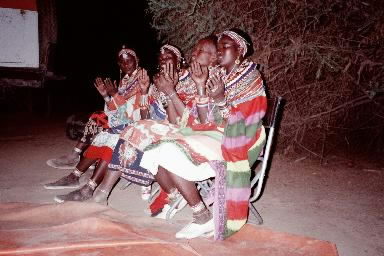

women sing along

women sing along

According to Nigel Paritt's book "Samburu", some young Samburu men now drink and smoke. But to my eyes, it was more than just a few young men.

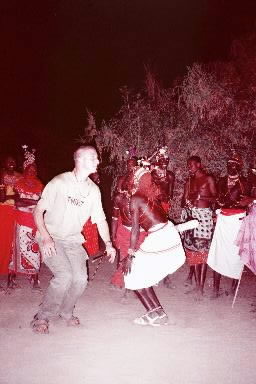

Trigger learns to dance with the Samburu

Trigger learns to dance with the Samburu

After the entertainers left, the group chatted and gossiped about people they'd met on earlier legs of their trip together. They'd been on what had been proclaimed the "Love Truck" and the passengers had behaved like drunken rabbits. This horrified me but even worse, most seemed to think this had been an enjoyable experience. I made a beeline for the safety of the little blue tent and noticed that Monica had erected her tent near mine, on the anti-social outskirts of the campsite.

cultural encounter

cultural encounter

SAMBURU TO MARALAL

OCTOBER 17

Some inconsiderate camper deposited a huge pile of poo and toilet paper on the walk during the night. Perhaps they had been too sick or lazy to make it to the long-drop squat toilet. Perhaps they didn't realize that Monica and I were inhabiting Samburu Camp's outer suburbs. Regardless, it made for some complex navigation before breakfast.

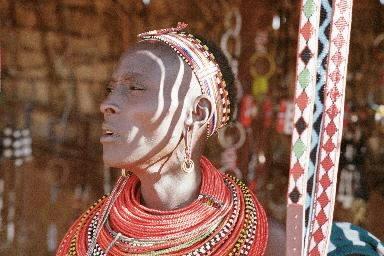

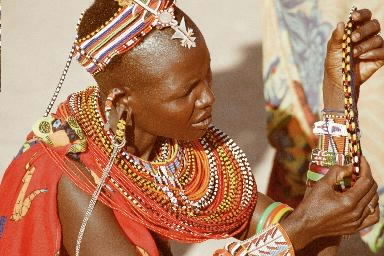

sassy Samburu

sassy Samburu

On the way to the truck, we noticed little footprints in the dirt, bearing "Michelin" and "Firestone" insignias. The Samburu had sandals made of old recycled tires.

Steven took us up to the Samburu village. The women did tribal dances and Steven pointed out the clothing differences between married and unmarried women. The men made us a fire without matches.

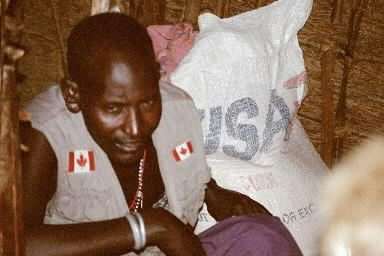

Steven brought us into his mud hut, where we sat on our haunches to admire the sacks of aid food labeled "USA."

Steven at home

Steven at home

The tiny huts were cool in the desert heat, due to their small windows and near darkness. Samburu are polygamists and Steven expressed concern that he might be forced to take a second wife due to tradition.

"But one wife," he conceded, "is enough."

inspecting the goods

inspecting the goods

The nearby Catholic mission processed the village's funds for them, so we were encouraged to buy souvenirs -- in any currency. Peter bought some intricate beaded collars to hang on his wall at home. I contented myself with browsing -- there was no hard sell here. The proud Samburu were happy to have our group patronage money to add to the school or save for a sharp student's education -- but they would have gotten along without our income.

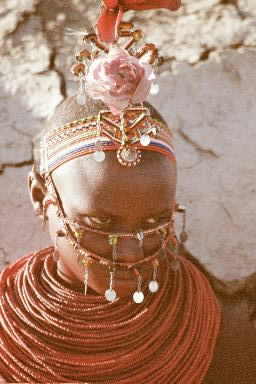

single but looking

single but looking

We shivered at the sight of a 16-year-old girl decked out in "single-but-looking" beads. Sixteen was, by Samburu standards, a fine time for marrying. I spoke to Claudine, a 29-year-old from the UK. "Just imagine," we agreed, "that this is all you know and can hope for." I tried not to.

available ladies

available ladies

Back on the truck, everyone took their customary seats. Boarding early to get a better space was pointless as everyone left possessions on seats as place-holders. It was, I realized, pointless to argue. Let them keep their seats, I thought. I'll do better on the next leg.

warriors start a fire

warriors start a fire

We continued what would soon be routine of driving for a long, hot day and then setting up camp in a remote, unpeopled area.

Our drive took us to a campsite near Maralal. I rented a $4 a night banda -- a cabin with a private bathroom -- did my laundry and rinsed the mud off the bottom of the little blue tent. I made a few tent modifications with the Velcro Sew-On Spots that my friend Lynne had given me back in Berlin. The group was having drinks in the bar and in an uncharacteristic social moment, I decided to join them.

Then, suddenly and inexplicably, I was having fun and enjoying the company of others.

Monica, Trigger, and Charles chatted. Mark and Sam dropped by to discuss Kenyan politics and their own backgrounds.

Sam technically owned a farm in southern Kenya, but had for all practical purposes handed it (and his dog) over to his mother while he went to seek his fortune in Nairobi. He'd found work there painting

trucks and doing odd jobs. He'd met Mark, who had noticed his sharpness and reliability and gotten him work as a Dragoman cook as soon as Dragoman had introduced cooks on their African trips. Sam had just been added to Dragoman's insurance as a driver-trainee and was probably the first native African to earn Dragoman driver status. I hoped he was proud.

Mark turned out to be childhood friends with Dave Briggs, the Dragoman driver immortalized in Jeff Greenwald's "The Size of the World" book, and on JetCity Jimbo's "It Will Be So Awful, It Will Be Wonderful" website. "Briggsy" had recently left Dragoman for Massachusetts, after escorting my friend Steve on one of Dragoman's final hotel trips through the Middle East.

"Dave gave me a copy of 'Jupiter's Travels' once, and said when I was done reading it he had a question for me," explained Mark. "That question was when do we leave?"

They'd saved money for a few years and then ridden motorcycles around Africa and Europe together. Later, they'd both become Dragoman drivers at a time when adventure travel was still too adventure-driven to adhere to schedules. Mark's first trainee trip across Congo had fallen something like eight days behind, and he'd been sent ahead of the truck by public transport, ending up in some nowhere town like Kabale while waiting on the group.

I returned happy to my banda. My anti-group hysteria had evaporated for the moment. Maybe the little blue tent and I would make it to Ethiopia after all.

MARALAL

OCTOBER 18

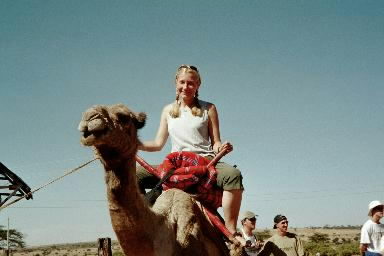

The point of a camel safari is not to see camels, it's to ride them. By riding an animal, you fool the wild animals into thinking you are but an extension of a camel -- perhaps a hump -- and you can get close to the wildlife.

Marie and Masagarai

Marie and Masagarai

Our camel safari, however, did not work that way. Our three Samburu boy guides, decked out in traditional blankets and non- traditional Oakley-style sunglasses, chattered loudly amongst themselves as they led our camels by the reins. Any nearby animals were long gone by the time we got there.

"Can I drive?" I asked the boy leading my camel. He smiled uncomprehendingly and told me my camel was named Masagarai.

"Did Masagarai win the Derby?" I asked. Every summer, Maralal hosts a famous camel race.

off to look at goats

off to look at goats

"No," he laughed. "Masagarai was working in Turkana then."

I was certain my camel would have won the Derby had he been given the opportunity. I was not so certain later, as we plodded along in a slow and rigid line en route in the hot sun to nowhere, really.

here be camels

here be camels

"We're going in circles," said Charles, an ex-travel agent from the UK. He was right. There wasn't anything to see but farmland, so the Samburu were leading us in goat-viewing circles.

Eventually we stopped for lunch, which was a forced hour and a half long. We had no desire to spend an hour and a half by a tree, but since we'd already seen the same goat six times there didn't seem to be

much else to do.

After lunch, we plodded on, wondering how the four who had skipped this activity had known that it would be so dull. Then it livened up a little when Trigger's camel bit Charles.

"Ow!" said Charles. "It bit me!"

The Samburu laughed. "He just licked you," they said.

vicious biting camels

vicious biting camels

The camel bit Charles again. So he punched it in the head. It only looked mildly perturbed by this, but at least this time the Samburu saw and changed the order of the camels so that Trigger was at the front of the line.

Sam had cooked us dinner and given it to Mark who came out on the back of a Jeep to meet us. He'd brought along tents, our sleepingbags, and our gear to stay the night in the "wild." But we were having none of it. We were dirty, hot, and only a few miles from the campsite, so we made him turn around and go back with us to the comfort of bandas, flushing toilets and showers.

Everyone agreed. "If we were actually out in the wild, we'd like to bush camp, but we're on someone's farm and showers are so nearby we could almost sneak to camp for a wash."

Mark was taken aback at this turn of events, but he rolled with it and carried the beef stew right back into the Jeep.

The Samburu instructed the driver on the best way to drive back to the road, which resulted in him driving to an impassable ditch and having to back up and go around.

out for a stroll

out for a stroll

"The Samburu cannot discern between a road and a footpath," explained someone, possibly Mark. "It doesn't occur to them that a car cannot travel the same way they can."

When we got back to the campsite, Mark left us at the gate and went off to sort out some details with the receptionist. So Sam heard that the passengers were back, assumed something was wrong and that Mark was somewhere out in the wild farmlands with a beef stew. Sam was just about to hire a taxi to go and hunt for Mark, when he learned that we had all returned, even the stew.

And serendipity was on our side, because as it turned out, one of the passengers who had stayed behind had been contacted with some disheartening results from a medical test in Nairobi. She suddenly had to leave Africa to fly home to the UK for an operation. Claudine was going to accompany her as far as Nairobi airport, for moral support. A private taxi was going to pick them up in the morning, and Mark was needed to arrange things at camp. Claudine would fly from Nairobi to Addis Ababa, meeting us for our loop through Ethiopia.

Monica shared a banda with me this time. It turned out that she was as alienated as I was, and we bonded and giggled into the night.

NEXT: the promised answer to the scientific question of what happens when you drop the left side of a 16-ton truck in clay.