I'd Turn Back If I Were You

(Marie-mail #49)

KARIBA TO CHIRUNDU

SEPTEMBER 3

I was up early, but felt no compunction to be quiet or polite. My lodge neighbors were less subtle in their revenge on the campers next door. They turned their car stereo on to full volume and blasted country music. I gave them a thumbs-up.

I met my fellow canoers at reception. We were loaded onto a 4x4 that pulled a trailer full of canoes, and drove to a grocery store for last minute supplies.

Two Cokes, some film, and one Snickers bar later, we drove the two hours to the put-in point at Chirundu. I watched the signs from the Mana Pools turnoff. On the return trip, I'd have to hitch forty kilometers to get to the border.

putting in the canoes at Chirundu

putting in the canoes at Chirundu

Put-in involved loading everything off the canoes, dragging them into the water, and reloading them. We were assisted by several enthusiastic local boy helpers, and Aussie Lisa thanked them with a Polaroid photo of themselves.

Bono gave us a canoe safety talk.

"There are four things to watch out for on the Zambezi. One: crocs. Don't stick your hands or feet in the water. Two: hippos. they have four-inch teeth. Let them know you're here like this." He tapped his paddle loudly on the canoe.

Bono the guide

Bono the guide

"Three: visible tree stumps. Avoid them. Four: tree stumps below the surface. You can identify they by the way the water flows on the surface. Okay?"

He demonstrated paddling with three strokes on each side, and told us that the person at the back of the canoe had eighty percent of the control over the canoe (and did eighty percent of the work). My tent mate Sara and I looked at each other. Who would be in the back?

Neither, as it turned out. We were each riding in the front with a guide driving from the back.

We all applied sunscreen, put on our stupid floppy hats and sunglasses, and positioned ourselves for push off.

Ten minutes later, I was clumsy, sweating, and wondering why I hadn't realized that a canoeing safari would involve physical exertion.

To make it worse, I was getting nowhere for all my rowing. I had no power, and dripped water all over the boat every time I switched hands.

We rowed for a few hot hours, ineffectively using a lot of energy for each movement. Finally, we stopped for a quick lunch.

row row row your boat

row row row your boat

A table, some plates, two washing buckets, and sandwich fixings came out of a canoe. We were treated to a traditional camping lunch of pink meat and cucumber sandwiches -- something I never imagined myself eating, but now consumed without complaint on a regular basis.

Post-pink lunch meat, everything went back on the canoes and we were off again. I was a little less clumsy now but still struggled to get an forward movement out of my feeble paddling.

We passed some hippo pools, and then the wind came up against us. I had struggled before, but now I had to work even harder.

hippos!

hippos!

"I thought this was supposed to be fun," I thought right before wondering if it was possible to get off early and catch a ride back to Kariba.

Finally, we stopped and set up camp. Two tent poles were unexpectedly missing, so Bono and Cambell rigged up their tent using two long sticks.

Bono issued some more instructions.

"After dark," he said, "don't go anywhere near the riverbank. That's when the crocodiles hunt. And at night, if you need a toilet, don't go more than ten meters from your tent."

just waiting to eat a canoer

just waiting to eat a canoer

This was a bit alarming, as I'd just been considering sneaking down to the shore to wash.

The sun turned a dramatic orange before plopping down behind the horizon. Bono made us a dinner of rice, chicken stew, and the ubiquitous African gem squash I'd taken to. Everyone was exhausted

and asleep on our Shearwater sleep mats by nine, in spite of the possibilities of man-eating wild animals.

LOWER ZAMBEZI

SEPTEMBER 4

Breakfast was fried eggs, baked beans, toast, and sausage. Aussies put their baked beans on toast, and Cambell grossed me out by adding peanut butter to the mix.

My arms were, miraculously, not sore. My fingers and palms, unfortunately, were tender and cramping. I'd obviously been gripping the paddle too hard.

The wind was with us today, and canoeing was easier. We pushed off, and I made a much smaller mess this time. I didn't pour water all over the bottom of the canoe.

hippos galore

hippos galore

About a half-hour after pushing off, we encountered a huge pod of hippos stretched across the river's narrow width. I was in the lead boat with Bono, and had thought this advantageous as Bono was the man carrying the loaded warning pistol. Now, as he carefully led the way through the hippo pool, I realized that being the first to surprise a hippopotamus was less than ideal.

Hippos are grass-eating vegetarians, but they are also timid and don't like to be seen or surprised. Every time we approached a group of hippos sun-bathing on the bank, they'd turn bright pink with shame at their out-of-water nakedness and flee for the safety of the water.

The hippos we now approached were already in the water, but it didn't make them less fearful. To intimidate us, they emitted their very un-hippo-like ominous roar -- it sounded like the disembodied Jolly Green giant -- and seemed to warn us away.

"Ho ho ho," said the hippos.

"I'd turn back if I were you. That's what they're saying," I thought.

Bono slowly paddled us into the middle of the pod. He kept tapping his paddle, making noises to let the hippos know we were coming.

"Stay close," he said to the rest of the group.

Then, we cleared the first line of defense and looked at the water before us. Hippos were exploding out of the water - here a hippo, there a hippo. They can stay under water for five to six minutes and when they come up suddenly, the result is a massive expulsion of air and water followed by a surprised, possibly annoyed pair of eyes and a snout.

I was wondering if Bono was lying to me about the hippo that could bite a canoe in half when he started issuing instructions.

"Follow me," he barked. He's been aiming right for a hippo and now suddenly cut directly across the river.

"Paddle left," he told me. And I did. I paddled furiously on the left. If we didn't make it in time, I'd be the first one bitten by the unhappy hippo.

We made it in spite of my feeble contribution, as Bono was much stronger than I was and was well-versed in the twists and turns of the Zambezi. We were never really in danger, but it sure felt like we were.

Now, I understood the appeal of the Lower Zambezi canoe safari. It was just you and nature, face to face. And while the danger did exist, it was easy to minimize it with a qualified guide.

Enthusiastically, I quit telling myself that it mattered if I paddled, and took it easy. I took as many photos as I did strokes. We were ahead of schedule anyway, and Bono told us to slow down.

Slow down we did, observing more hippos, some evil-looking crocs, elephants, egrets, and carmine bee-eater birds that lived in muddy holes.

carmine bee-eaters are birds that live in holes

carmine bee-eaters are birds that live in holes

Eventually, we stopped for lunch. The pink meat was abandoned in favor of cold chicken which Cambell tried to pawn off as guinea fowl.

Lunch was followed by a siesta in which I wrote, some slept on the camp mattresses, some watched a nearby hippo pod, and Bono studied a book on African wildlife. Eventually we started up again, leisurely rowing the last five kilometers to our island campsite.

curious about canoes

curious about canoes

Sara had caught on quickly to tent-erecting, and I already had some experience in that. We had both learned to paddle. Unfortunately, neither of us was keen to learn the camp toilet system, because it was unsettlingly public.

Sara has mastered rowing

Sara has mastered rowing

"Where's Doug?" Australians were not shy about these things. "Doug" was the name given to the small shovel we were expected to request every time nature called. Doug would dig the hole and the tourist would squat over it.

"And Lucy the loo roll?" Doug and Lucy went hand in hand. A roll of toilet paper permanently resided on Doug's handle.

And in case everyone hadn't already clearly gotten the point that someone was going off into the woods to have a bowel movement, the Doug and Lucy search would be followed by a long search for the matches. Used toilet paper was to be burned.

Bono and Cambell, I noticed, were much more subtle in their patronage of Doug. Sara and I both made a pact not to eat much. I also reminded myself to get my own matches for future camping trips.

The downside of the wind dying down was that the heat increased. We were all stinking by the time we'd reached an island and set up camp.

"Please can I wash, just here near the canoes?" I pleaded. Bono surveyed the area with great seriousness. He didn't want one of his passengers to be eaten by a crocodile.

"Okay," he said. "But just right here, and only while the sun is up."

We all changed to our swimsuits and soaped up, rinsing off with mugs of water. Sara, who had misplaced her swimsuit (that's "swimming costume" in British) made do with a bucket and a tree.

campsite with towel as Zambian-bait

campsite with towel as Zambian-bait

Refreshed and with dripping hair, we all gobbled up the spaghetti bolognaise the guys served us and were again ready for bed by nine.

More to make conversation than for a serious answer, I asked Bono if it was safe to leave my towel and bikini hanging from my tent.

"No," he said. "The Zambians might take it."

Startled and skeptical, I stared at him. The problem was that he had a clever, dry sense of humor and I couldn't tell if he was serious.

"Really?" I asked.

"Yeah, seriously."

"Do you think he was serious?" I asked Sara, back in our tent.

We decided he was -- not that Zambians have any great desire to own a mangy quick-dry Aquis travel towel or a bikini with the top and bottom in two different sizes, but the fact was that the Zambian side of the river was filled with villages and people. the Zimbabwe side was all national park, and while it was possible to be eaten by a Zimbabwe lion, it was unlikely that such a lion would have a taste for Billabong. I took in my clothes and towel.

SEPTEMBER 5

The usual baked beans and fried eggs awaited me. I'm not big on fried eggs, and already missed my instant oatmeal. But that was nothing compared to the instant chicory coffee our guides had brought along. I regretted my decision to leave my good coffee back at the Shearwater office.

Marie's Travel Lesson #1: ALWAYS bring your own coffee.

We paddled slowly down the river to the scary soundtrack of hippo warnings.

"Ho ho ho," said the hippos.

"Have you ever seen 'Deliverance'?" I asked Bono. I knew it was a cliche to say that on a canoeing trip, but the atmosphere was so ominous that I couldn't help myself.

"No." He'd never even heard of it.

At lunch we indulged in some more pink meat and cucumber treats. Everyone else wandered off and left me scribbling in my diary and contemplating Doug.

Then, they all came scampering back, wide-eyed and agitated.

"Ellies," said an Australian. Aussies like to shorten words, and what they meant here was that elephants were headed towards us.

I noticed that Bono had the pistol in his hand, and Cambell had the radio. It was on.

Everyone had left their possessions on the bank, fleeing with just the clothes on their backs.

"If an elephant charges," instructed Bono. "Stand still."

We looked at him like he was mad, but there was no time to argue.

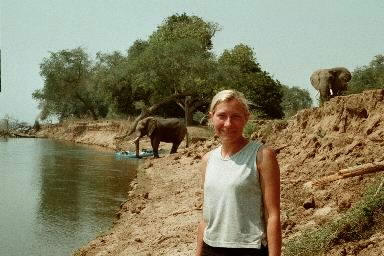

if you go out in the woods today, you better not go alone...

if you go out in the woods today, you better not go alone...

The elephants approached. It was hot out, and they were headed straight towards our canoes for drinks and showers.

The elephants inadvertently herded us.

"Everyone over here," said Bono, motioned us further on, out of the elephant's way.

The elephants had a good long look at us and seemed to decide we were not worth their time. They stalked on, to drink and splash about while we cowered and snapped our once-in-a-lifetime photos.

Finally, the elephants left. High on adrenalin, we reclaimed our possessions.

But it wasn't totally over. Five more "ellies" approached, shaking the berries off acacia trees as they walked. This time they approached directly, driving us up onto the bank. We were cornered, our only out a leap into the croc-infested river. But the elephants didn't care about us. They only had eyes for the cooling effects of water, squirted onto their backs by their pendulum-like trunks.

The most amazing thing about the African elephant was not the size of its enormous ears, which flap to provide elephant air-conditioning. It was their sensitive, delicate step. They avoided our canoes and possessions and even Doug -- without so much as a glance.

Finally, they left the water's edge and moved away, intent on tormenting more acacia trees.

Buffalo wandered up next, along with waterbuck, a type of antelope/deer thing. Both had the sense to keep a fair distance away from us.

"Still want to go on that game walk?" joke Bono. We'd been pestering him for a game walk, but he'd been resisting because it wasn't legal to go walking in the national park.

Nobody wanted to go. Why go for a game walk when the game will come to you?

human footprint in elephant footprint

human footprint in elephant footprint

Our last seven kilometers were slow, and I only made a token effort at paddling, preferring to turn my Canon on the ferocious-looking crocs that adorned the banks.

"Hey," yelled a man from the bank, where he was fishing with his son. "Is this where that croc killed that man a few years ago?"

"No," said Bono. "It was back there." He pointed behind us.

"Um, Bono," I asked nervously, "are we camping around here?"

"Yes," he answered.

We pulled up shortly, and set up camp on a sandy island. Now another tent pole was missing, so our guides decided to just sleep on top of their flattened tent. I thought they were nuts with all those crocs around, but they set up a ring of stools. It was probably as effective as a thin layer of canvas.

The stars were out in force, and the Milky Way was clear. We stared for a while, and then Sara and I went back to our tent and talked about Zimbabwe.

"It's a fantastic country," I said. I meant it. I had come a long way from despising Vic Falls, and meant what I was saying. "What a shame that things are going to hell."

"Yeah," she agreed. "They're expecting food shortages and food riots, because so many of the crops failed or were burned. And the people here are so peaceful -- they hate fighting. I hope our guides have an escape plan."

Popular opinion held that Mugabe, who would likely lose a truly democratic vote, was going to call a state of emergency in order to delay the spring 2002 election. And the elections, if they went ahead, would almost certainly be rigged.

On that note, we tried to sleep. It didn't really work out though. Elephants splashed nearby, hippos had a nearby social gathering, ducks quacked, and lions on the mainland roared all night.

I left my towel out. No Zambians took it.

LOWER ZAMBEZI TO LUSAKA

SEPTEMBER 6

Bono and Cambell were still with us in the a.m., so fried eggs and chicory coffee were a certainty. They didn't get any more sleep than we did.

"It was quite noisy last night," observed one of them in a typical understatement.

We packed up and drifted off. Our morning went something like this.

Paddle.

Paddle.

Paddle.

WHOOSH HO HO HO

Paddlepaddlepaddle!

Paddle.

Paddle.

The whoosh and subsequent laughter was just our friendly neighborhood hippo pod, letting us know that no matter how many times Bono tapped his warning on the canoe, we could still be surprised.

like a hippo out of water

like a hippo out of water

It was just a short trip to Mana Pools, where our Shearwater safari was ending. A truck was waiting for us, complete with a cooler full of cold drinks.

It was still a filthy, hot two-hour drive from Mana Pools to paved road, complicated by frequent stops for crossing zebras and waterbuck. We were jostled and bumped -- and covered in a layer of dust -- until we reached pavement.

We turned left. The border at Chirundu -- my route to Lusaka -- was right. The truck pulled over. I fully expected to be left by the road to flag down a passing bus.

Instead, the canoe trailer was unhitched and the group was served lunch while Bono and the driver whisked me to the border.

"That was easy," I thought, after they left me at Zimbabwe customs.

Nothing else was easy for the next several days.

I waited in a long line, having reached Immigration behind a bus. I considered just walking through without a stamp. There was no one to stop me.

Then the Immigration officer in front of me quit working. It was the border equivalent of the grocery store clerk putting up the "next aisle" sign after you've been waiting in line for fifteen minutes.

"Please," I begged. "I've been waiting a long time. Please just give me an exit stamp."

He stared for a minute and then stamped me out.

The bridge across the Zambezi was long and the walk -- with fully-loaded pack -- was hot. With some relief, I noticed that the Zambian Immigration office had air conditioning.

But it taunted me -- the bus had arrived ahead of me again, and it took twenty minutes before I got through the door and into the air conditioned madhouse within.

It took a full hour and an unexpected forty dollars to get into Zambia.

"But all I want is a ten dollar transit visa!" I said. "I'm leaving for Tanzania on a train tomorrow."

The officer didn't care. He was careful to give me an official receipt. He was, after all, just following orders.

The Customs fun and games were still not, unfortunately, over. I had to wait in another long line for forty minutes, so that a man in a uniform could wave me through a gate -- no doubt an important part of the Zambian immigration system.

I saw my day in Lusaka evaporate in sections. Doing my laundry was out after Zimbabwe, a visit to Subway was out after the Zambian visa session, and the possibility of lunch was gone altogether after my wait in the hot sun.

A minibus waited on the other side, and in about fifteen minutes it was full of the requisite 16 adults and 3 children. My feet were up on boxes, and I realized I don't really have the knees for this sort of travel as they were in agony (as usual) after the first half-hour of traveling this way.

Two hours later, I got a taxi from City Market to Chachacha Backpackers. In spite of its cockroaches and local bar scene, it was the best source of Zambia information outside of Zambia Tourism itself -- and was only $6 a night.

Opting to wear my Zimbabwe dust downtown, I raced to buy a bus ticket to Kapiri Moshi (where the train was leaves from) and stock up on groceries for the marathon trip to Dar Es Salaam.

The bus left at 7, the train left at 12:30, and -- to my horror -- the train trip was 50 hours. I had thought it was only 36, but the express train had become an ordinary train since my guidebook was published. I'd need a lot of peanut butter and strawberry jam for the trip.

I had some allergy-free instant soup, but Dennis from my Nomad group had given me some bad news.

"Is there hot water on the train?" I'd asked him.

He'd laughed. "There's NO water on the train." He'd thought it was even funnier that I expected to book my ticket in advance from Lusaka.

"They tell you that you can book in Lusaka, but that doesn't work. Booking doesn't work at all. Just show up and hope you get on."

I fancied myself pretty sharp for having managed to pre-book at the TAZARA office. I'd even followed up my booking with an international phone call, confirming from Zimbabwe.

Chachacha Backpackers has an evening meal every night at seven, and it had looked good the last time I'd been there. I left downtown Lusaka in plenty of time to make it back, but friendly locals kept stopping me to chat. I was five minutes late for dinner.

"Are you Marie?" asked the cook. "I've been looking all over for you. I was walking downtown yelling your name!" He laughed. At least I wasn't in trouble.

The Chachacha barbecue was great, and I ate with a couple from Florida who had just come in on the TAZARA train from Dar.

"It's great," they said. "First class is comfortable and has a nice lounge. And there's no water, but you can get hot water from the dining car."

That sounded tolerable. In spite of the aversion I'd developed to trains, I could do this.

I finally had my shower, washing the day's dirt away. Lusaka's municipal water supply cut off ten minutes later.

NEXT: Galloping... giraffes? By train into safari country.