On the Bus

(Marie-mail #48)

WINDHOEK TO VICTORIA FALLS

AUGUST 27

Again, I caught the overnight Intercape Mainliner. I had a new appreciation of the luxury bus, after traveling by local bus, hitch, and overland truck.

The bus was half-empty this time, and I had two seats to myself. I made good use of them, sleeping as soon as the lights went out. I was careful not to crush my breakfast or lunch. This time I knew what we were in for at the food stops.

back to Vic Falls on the Intercape Mainliner

back to Vic Falls on the Intercape Mainliner

At one a.m., the bus stopped in the middle of nowhere. The lights went on, and we were all instructed to get out.

"Census," said the driver.

We were all getting off the bus in the middle of the night in northern Namibia to be counted by the census.

Three census workers sat under generator-powered lights at a table in the center of the highway.

Marie's Namibian civic duty

Marie's Namibian civic duty

The police stopped every vehicle that came by, and set its occupants over to be counted.

The questions were simple -- what is your nationality, where do you live, and where were you born. For some reason, it took a half-hour to process everyone. The census workers were being thorough.

VICTORIA FALLS, ZIMBABWE

AUGUST 28

I checked in to Club Shoestring, the hellish backpacker's compound crawling with cockroaches and overland trucks. But it was tolerable for one night, the staff was helpful, and I was too lazy to walk any farther.

The usual army of money changers, taxi drivers, and curio sellers accosted me. I ignored them and headed for the large crafts market behind the post office. I was in need of some souvenirs for my sponsors.

"Madam, see my art! Buy straight from the artist!"

Clearly, everyone who said this was not really an artist, but a clever salesman.

"Buy direct, only four thousand Zim!"

I surveyed all before settling on the guy who'd offered me the lowest price to start with. I patronize those who start low because I don't like to encourage the ripping-off of naive tourists who don't realize they are supposed to bargain. I personally don't bargain for the best price -- tourists also have a responsibility to put money into the local economy -- but I always settle on what I think the souvenir is worth. It's a compromise I worked out somewhere along the way in my travels, and one that means I don't care if someone else got a better price.

"Special sunset price" was a new phrase I added to my shopping vocabulary. Also, many sellers tried to trade me art for my shoes or watch.

I left with three excellent souvenirs, wrapped up by a guy who asked if I could send him a miniature Statue of Liberty figure.

"I have been in Zimbabwe my whole life and have never known freedom. That is why I want a Statue of Liberty," he said.

I was skeptical. It sounded rehearsed, and living in Zimbabwe is hardly the same as living in a totalitarian state. I wished he had just told me the truth -- maybe he wanted it for a collection, or maybe he wanted to copy it in his own art. I'd understand that.

I explained that I wouldn't be back in New York for many months, and agreed to ask one of my friends to consider sending one.

"No promises," I said.

I walked back to the town center, accompanied by two teenage boys, done selling for the day.

"Why do they want my shoe?" I asked.

They surveyed my shoes, a pair of hybrid Montrails.

"They're good shoes. It is hard to get such good shoes here."

It hadn't been easy to find them in Hong Kong either, I thought. I explained why I wouldn't give them up.

"They wanted me to trade Zimbabwean art for my shoes. How silly would I look with wooden elephants on my feet!"

The boys agreed.

"Where are you staying?" They asked.

"Club Shoestring," I responded.

"How much to stay there?"

"Seven dollars a night."

They laughed.

"So you are a millionaire." Now I had teenaged Zimbabwean boys poking fun at my budget.

They left me at the crossroads. I went back to Shoestrings, where there was no running water.

"Sometimes the town cuts off the water," explained the woman behind the bar. "We have our own tanks, but they run out. Try the campers' shower. I heard there's still water there."

There was, and I managed to get clean. I was having to alter my ideas about travel in Africa. Here, I was constantly filthy and always called on to supply my own sleeping bag and towel. I'd been comparatively clean and catered to in the rest of the world.

VICTORIA FALLS TO LIVINGSTONE, ZAMBIA

AUGUST 29

The "Pink Baobab Cafe" was under attack by baboons. They bounded energetically though the eating area, scampered up trees, and pounced onto the tiny roof. Everyone stared, not sure what to do. Six baboons racing along a tin roof make a loud racket.

pesky baboons in Vic Falls

pesky baboons in Vic Falls

I sent home my souvenirs after eating pancakes, and idly considered purchasing a six-foot-tall wooden giraffe. Instead, I occupied myself by searching for a working internet cafe. Finally, I located one across from the supermarket. The connection was so slow that the guy across from me managed to read the entire newspaper while checking his e-mail.

For one dollar, I got from Shoestring's to the Zimbabwean border post on the Zambezi Bridge.

Leaving Zimbabwe, I hiked the kilometer to the Zambia side. Halfway there, I passed th bungy jumping station. A teenage Zimbabwean girl was being suited up.

looking down from the bridge over the Zambezi. Would you bungy jump from here?

looking down from the bridge over the Zambezi. Would you bungy jump from here?

They strapped her ankles together and she hopped to the edge. She looked at the gorge and then at the fraying massive rubber band, and decided that it wasn't for her.

"I've changed my mind," she said breathlessly. "I can't do this. I'm sorry. I can't do this."

They released her. Relieved but embarrassed, she backed away.

I walked on, and arrived early at the Zambian border post. Fawlty Towers Backpackers was picking me up. They offered a package deal -- free visa, transfer and two night's dorm accommodation for twenty US dollars.

The Fawlty Towers rep showed up early too, and I was soon installed in my own six-bed dorm room before my scheduled pickup time.

Fawlty Towers was lovely. The facilities were immaculate. The only other female occupant had her own dorm room as well, and there was a great restaurant in the backyard.

Tonight, unfortunately, the menu was fish.

I walked to the "Funky Munky," a few doors down from Fawlty Towers, and got a vegetable pizza without cheese. The proprietor looked askance, but didn't remark on the weirdness of my request.

LIVINGSTONE

AUGUST 30

I woke up early and admired my room. The doors and floor were bright red, with green accents. Sheets and pillows were provided Playful animals were painted on each bunk. Lockers, as in most hostels, were provided but you had to bring your own lock.

The showers always had hot water, and tea/coffee were free. I utilized the electric water boiler, but shunned the Nescafe in favor of my Namibian java and tiny filters.

I took my coffee and instant oatmeal to site on the verandah, which overlooked a lush garden. A single backpacker had erected a tent by the pool. Bids sand, someone was sweeping rhythmically, and cars went by in the distance.

I hadn't expected to love Africa, and it had caught me by surprise. Africa had just been a place on my "to do" list.

TO DO:

Wash clothes

Buy toilet paper

See Africa

It was an obligatory continent that required visiting because aside from Antarctica, it was the only one I'd never seen. But the open savannas, wildlife, and easy attitudes of southern Africa had caught me off guard and charmed me. And while I wasn't fond of the massive overland truck scene, the more intimate backpacker's network -- something I'd shunned in crowded southeast Asia and Australia -- was small enough to be appealing. Facilities were pretty good.

Fawlty Towers, I decided, was on my top three hostels list. The other two were the Shanghai YMCA and the Lutheran Hostel in Jerusalem.

At eight, I went out front. "Safari Par Excellence" was picking me up for a half-day of whitewater rafting.

I didn't want to do a half-day. Lars and Carina had told me to do the full day, because the second half-day was less scary and there was a barbecue at the end. But I was desperately in need of world currency -- the US dollar -- and needed to get to the bank before its 2:30 closing time.

I was the only customer from the Zambia side of Vic Falls today, and everyone else was coming from Zimbabwe. I rode in with the staff.

Headquarters was the "Zambezi Waterfront," a posh development I would've stayed at if I hadn't opted to return to Namibia for the weekend.

We checked in, signed indemnity forms, and paid. It wasn't cheap -- $85 for the half-day as well as the full-day. We were stuffed full of egg sandwiches and sent off in an enormous 4x4.

Two other vehicles accompanied us. The World Whitewater Championships, or Camel Cup, or something like that were going on, and Safari Par Excellence was ferrying teams to the Zambian put-in point.

The professional teams put us tourists to shame. They all wore wetsuits adorned with their home flag. The German and Australian men's teams were putting in with us, to practice and get to know the river.

At the put-in point, one of the tourist teams was looking for a teammate.

"One more, we need one more," yelled a Kiwi woman.

I joined up, got a tight-fitting lifevest, a loose helmet (it was the smallest they had), and a paddle.

The steep walk into the gorge began. It was rocky and long but only difficult at the very bottom. One of my teammates, a small, sweet Japanese woman who had obviously never done an outdoor sport in her life had great difficulty with the descent, and I worried that she'd have trouble on the Zambezi.

Our guide, Petros, was himself on the Zambian national rowing team.

"Doesn't the Zambian team have an advantage here?" I asked.

Petros shrugged. "A lot of my co-workers are from other countries, and they have joined their home teams. They know the river as well."

We put in at Rapid #1, an eddy on the Zambian side that the guidebook described as "the closest you can get to the falls in a raft."

"You have to paddle hard to get out of the eddy," explained Petros.

Our best was not very good. We were an inexperienced team of six, and I seemed to be the most experienced of us -- not good when you consider that my experience consisted of two previous trips in Colorado and Costa Rica.

It took us three tries to get out of the eddy, and on the third, Petros made us paddle backwards.

The water was high, and we all got a thrill out of the spray and roller coaster feel to the river.

When we approached Rapid #8, Petros offered us a choice.

"If we go on the right, it is 100% sure that we will make it through. If we go through the middle -- the Muncher -- there's a 50% chance we'll flip. But if we go through the left, there's an 85% chance we'll flip."

The left rapid was called "Star Trek," possibly because it was like going into warp drive, or possibly because it swallowed people up to have them materialize later on the other side.

"Left, left!" yelled the Kiwi couple. Against my better judgment, I kept quiet and let them decide our fate.

The Japanese woman looked concerned. Petros assumed that everyone else was up for it, because no one said otherwise. He offered to transfer the Japanese woman to the "safety" raft.

The woman eyed the raft full of strangers. She looked at her boyfriend, who had never rafted before but was game to go through "Star Trek."

"I'll stay," she decided.

We rowed over to Star Trek, past the Muncher, and paddled into the maelstrom.

Our raft flipped instantly. The front hit the water and rolled towards me, and we were all submerged under the giant pice of rubber.

"Don't panic. And don't stay in the air pocket under the raft, because it's comfortable but your guide needs to know that you're okay."

There wasn't an air pocket under the raft and I realized I needed to get out from under the raft quickly, as it was merrily rolling along through rapid #8 with all of its former occupants trapped beneath it.

I drank a lot of the Zambezi as I gasped for air and tried to push myself out. The raging surface surprised me, and spray took my breath away. I swallowed more of the Zambezi.

The raft was next to me, as was the Japanese woman. We both struck out swimming and grabbed the rope around our raft's edge. Peter, the middle-aged man on out team, was laying stretched out on the top of the raft, panicked and hyperventilating. He'd obviously fared poorly, and Petros was comforting him, keeping him atop the raft in the face of the water's onslaught.

The rest of us hung on, gulped air and water, and enjoyed our descent into warp drive. The Japanese woman held on tightly and did not panic.

Finally, the water slowed and our raft became our friend again. Petros counted us, and reassured Peter.

But it still wasn't over. We had to flip the raft back, which involved several of us hanging on to the rope to tip the raft up, then taking a deep breath and ducking under as it pivoted over us.

Somehow, I made it though all of this without panicking over the amount of the Zambezi that went into my stomach.

"Okay, now we have to row hard and get to the edge," announced Petros.

Rapid #9 was known as "Commercial Suicide," because it is unrunnable, except by insane professionals, and Petros on a riverboard.

We all disembarked on shaky knees, and Petros sent our raft downstream alone.

We arrived safely but our raft was tossed around frantically arrived upside down.

We had one more mini-rapid to run, and then my half-day was over. Petros dropped me at the bottom of a 220 meter ladder made of tree branches.

Adrenalin got me halfway up, and then I had to rely on using my paddle as a walking stick.

At the top, I was alone. I waited for fifteen minutes. Maybe Safari Par Excellence had forgotten me.

I decided to walk to the main road. Maybe I could get a lift. I hadn't forgotten that I needed to be at the bank by 2:30.

I walked along, my lifevest and helmet hanging from the paddle, which was across my shoulders. A truck approached. It had the Safari Par Excellence logo on the side.

"You came out of the gorge alone?" asked the driver.

"Yeah," I responded, not sure why that was so weird.

We drove back to the pickup point. The video guy, who shoots the action so that tourists can take home expensive videos of themselves panicking, was waiting.

"Did you forget somebody?" he asked. He must have come up several minutes behind me.

The truck dropped me off at Fawlty Towers, where I changed quickly out of my wet clothes and into something more sensible for banking.

I went to Barclay's Bank first.

"Can I get US dollars on my credit card?"

"No. Sorry."

I was confused. Lars and Carina had done it, easily. I suspected there was another branch of Barclay's closer to the border.

The next stop was Standard Bank.

"Sorry, but Barclay's Bank by the border can help you."

I caught a share taxi to "Zambezi Sun," a posh hotel and shopping complex by the border They issued me US dollars without much complaint, and I stood by the road looking for another taxi.

One stopped. We drove to the border to look for other passengers, and then ended up in a side road, where all the locals went to hitch lifts to Livingstone. I was quite the sensation, and little girls stared and waved at me.

Back in Livingstone, I turned in early. I had to get up early to go to Lusaka tomorrow.

LIVINGSTONE TO LUSAKA

AUGUST 31

Saying goodbye to Fawlty Towers, I walked to the C.R. Holdings "Virgin-Lux" bus stop.

Getting on the seven a.m. bus -- a big, purple beast -- turned out to be a zoo, as Zambians and tourists alike jostled for favorable seats and luggage storage.

small town in Zambia

small town in Zambia

Finally, every ticket holder had a seat in the air conditioned coach. We left on time for the four-hour journey, accompanied by a Zambian news radio broadcast with the disheartening bit of information that Zambian schoolteachers were dying of AIDS in record numbers.

Our driver took us up a modern, paved road through the scenic Zambian countryside. We'd stop in small towns for passengers to get on and off, and locals would try to sell us trinkets and bananas.

An hour into the trip, we pulled over. The driver and his helpers lifted up a panel in the floor, flooding the bus with the smell of coolant. The driver reached in and pulled out the shredded remains of a fanbelt.

Fortunately, they had a spare. Someone put it on and we sped away.

At the end of the third hour, we'd shredded the second belt. And there was no spare this time.

Everyone got off the bus and milled about the shoulder of the road. Passengers started deserting, hailing crowded Lusaka-bound minibuses.

I waited a bit. I had time. I needed to get to Lusaka to book my TAZARA railway ticket on to Tanzania, but it was still early in the day.

bus or minibus?

bus or minibus?

Finally, after one, I decided I couldn't wait any longer. I had to book the that train as I was leaving Lusaka for Kariba in the morning.

I got in a minibus. The bus driver paid for me -- he was paying for everyone's ongoing tickets. Fourteen other adults and three children got in as well as a huge amount of luggage.

It was after three by the time I showed up, sweating and exhausted, at Chachacha Backpacker's.

Wade, the Chachacha boss, gave me some bad news.

"The TAZARA office closes early on Fridays."

"Then I've come here for nothing. I guess I'll just go on to Kariba then," I said, deflated.

Fortunately, Wade had a solution. He gave me the TAZARA supervisor's name, her exact location, and told me to go and see her.

I left my bag at Chachacha and grabbed a taxi. The supervisor was out, but a woman named Dorothy offered to make the booking for me on Monday morning. I thanked her and went for a walk around Lusaka.

Later, after showering in the ablution block in Chachacha's backyard, I met some Peace Corps volunteers. They were teaching fish farming to rural fishermen.

They explained their difficulties in spreading information about HIV.

"We are told to advise the women to use condoms if they think their husbands are cheating on them. But this means they'd have to be willing to confront their husbands. Most of them won't do it."

LUSAKA TO KARIBA

SEPTEMBER 1

It was hard to believe that I was beginning my ninth month of being on the road. In 2000, the trip had seemed so intangible in the planning stages.

But here I was, sleeping in (relatively) to seven after the Peace Corps girls had left at five. I made coffee in the camper's kitchen, packed a lunch, and dragged my stuff out of the dorm, where three men were still sleeping.

I hailed a taxi in front of the hostel. I had almost no Zambian currency left, and told the driver to take me to the ATM.

Zambia is one of those Visa only countries where Mastercard just doesn't exist. It had specifically brought along a Visa card on my world tour, because I had encountered this situation once before, when I ended up destitute in Ecuador before all the Citibank ATM's were networked.

"But it's my bank! Why can't I get money?" I'd begged.

These days, I don't leave the US without carrying all three cards -- American Express, Visa, and Mastercard.

The Amex is useful as a postal address, and th same offices that receive cardmember's mail also cash their personal checks in exchange for traveler's checks. So even if my Citibank card didn't work, I could pop over to Amex to access my funds. As a last resort, I could use a Mastercard or Visa to withdraw money from a bank or ATM, and could pay all the bills online.

The Mastercard, in theory, I could live without. But I liked to use it, because I got frequent flyer miles on it.

It was funny to be accumulating thousands of frequent flyer miles on hotel bills and group tours around the world -- in a year where flying was taboo.

My nearly-flawless credit card and cash scheme hit an unforeseen roadblock on this particular Saturday morning in Zambia.

"Out of service," flashed the ATM screen.

I looked for an exchange bureau, but stumbled onto a Standard Bank down the street. My Visa card worked, and my horde of cash and traveler's checks remained untouched for the moment.

I went to the internet cafe, scanned, and left my bag with the friendly proprietor. I walked down Cairo Road to look for breakfast.

I liked Lusaka. It was not a tourist-oriented city. The only site the Peace Corps volunteers had mentioned was the Subway sandwich shop.

Lusaka was a real, living African city, where people lived their lives without the benefit of hard currency derived from tourism. Children stared at me in Lusaka, where a blond, pale woman was not an altogether common sight.

I passed Shop-Rite, banks, something called The Great Zambian Pie Shop, photo processors, and cell phone stores on my way to "La Patisserie." The help there was wildly friend, as had been every Zambian I had encountered.

I had an orange juice and pastry.

"No, not THAT orange juice," I'd said when they tried to give me orange Kool-Aid. "The other orange juice." I wanted the 50% juice kind, not the 0% juice kind.

City Market, Lusaka

City Market, Lusaka

I picked up my bag and walked there blocks to the "City Market" minibus station.

City Market was chaotic, with hundreds of white and blue minibuses, all bound for different points in Zambia.

"Siavonga?" I asked a driver. He motioned me on.

"Siavonga? Kariba?" I asked again. Siavonga was the border post town at Kariba dam.

I was sent to the back of the market and motioned into a minibus.

Minibuses only leave when full, or overfull, as fifteen passengers and a driver can hardly be termed simply "full."

Prices are listed in every Zambian public minibus so I knew the Lusaka to Siavonga trip would cost me 16,000 kwacha, or $5.50. But I wasn't sure how long the trip was, or what the state of the roads were.

My return trip from Kariba to Lusaka had to be on Thursday afternoon, beginning the minute I came off the Zambezi canoe safari, if I wanted to catch the 12:30 Friday train to Tanzania.

"When does the last minibus leave Siavonga?" I asked the other passengers.

"Around 1500, 1600 at the latest."

My Shearwater trip ended at three. I'd never make it to Lusaka the same day. I needed a Plan B.

minibus conductor shows off

minibus conductor shows off

Finally, our minibus had its requisite fifteen paying adults two babies riding for free, and one driver. We pulled out of the parking lot, crowded and miserable.

We drove along paved highway for two hours, to the Siavonga turnoff near Chirundu.

So Chirundu was only two hours from Lusaka. If I could get to Chirundu at the end of my Shearwater trip instead of returning to Kariba, I'd have a good chance of making it to Lusaka.

The other passengers were obsessed with any broken or wrecked car by the side of the road. You could almost see them thinking "that could have been us."

The last 65 kilometers to Siavonga were over a deteriorating road, and took a full hour.

The minibus dropped me at the immigration post, and I was stamped out of Zambia.

A Zimbabwean taxi waited in the parking lot. I climbed in and we drove across the monstrous Kariba Dam and into Zimbabwe.

"Where to?" asked the driver, after I'd cleared Zimbabwe Customs.

"Kariba Breezes Hotel." It was the meeting point for the Shearwater trip, and featured a posh hotel and backpacker rooms.

"Kariba Breezes" was on the shore of man-made Lake Kariba. It was landscaped and breezy, friendly, and low-key.

"Can I have a backpacker's bed?" I asked the receptionist.

"Sorry, it's full tonight. We have a camping lodge but there is no en suite bathroom. The bathroom is nearby."

"How much is that?" I asked, worried.

"$360 Zimbabwean dollars.

At the current black market currency conversion rate, that was about $1.35. I took the lodge.

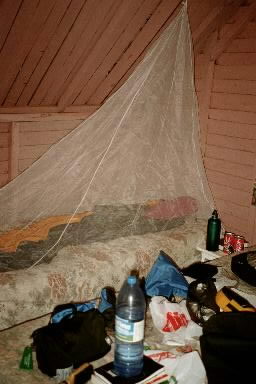

Marie's comfy lodge

Marie's comfy lodge

My lodge turned out to be a tiny, wooden A-frame hut. It was private, and I had to share my room with only a squirrel who lived in the roof. Four other identical chalets were nearby.

The ablution block was just up the hill, and featured clean showers and toilets, with hot water, and hand-laundry tubs.

At the current black market currency conversion rate, that was about $1.35. I took the lodge.

the lodge from outside

the lodge from outside

My lodge turned out to be a tiny, wooden A-frame hut. It was private, and I had to share my room with only a squirrel who lived in the roof. Four other identical chalets were nearby.

My chalet had a laundry rack, so I washed my clothes and hung them inside. I had been warned against hanging them outside -- baboons might come an steal my underwear.

I had a steak dinner alone in the hotel terrace restaurant and relaxed, happy to have nothing to do and no sights to see.

KARIBA

SEPTEMBER 2

I slept in, comfy under my mosquito net I'd erected before opening the windows the night before. I heard insects the breeze, and distant motorboats. I got up, had a hot shower in a bathroom no one else was in, and partook of the hotel's breakfast buffet.

My major project for the day was to walk up the hill to the gas station in late afternoon. I bought Coke and chocolate for lack of anything better to do, and started back down the hill.

more pesky baboons, Kariba, Zimbabwe

more pesky baboons, Kariba, Zimbabwe

A local woman stopped me.

"Please be careful," she said. "The elephants come out around this time."

I promised I wasn't going far, dropped my snacks off in my lodge, and headed to the 6:15 Shearwater canoe safari meeting.

Bono and Cambell were our Zimbabwean leaders. They introduced themselves and gave us an overview of the trip. We'd drive to Chirundu tomorrow, put-in, and learn to canoe.

We'd stop for a quick lunch on the first day but the next few days we'd have long lunches followed by siestas.

Days two and three would be canoeing days, and we'd go 17-22 kilometers a day on our way towards Mana Pools National Park. Our last day would include very little canoeing as it was a four-hour drive back to Kariba.

"On the last day, can you drop me off on the road to Chirundu?" I asked. That would be early in the day and would save me about three hours. Surely I could find a way from where they'd dropped me off to the border post, a mere 40 kilometers away.

"Yes, no problem."

"And you can arrange to have my bag brought along?"

"Yes. You just leave it at the Shearwater office with a tag, and the driver will bring it to Mana Pools on the last day."

Great. This could actually work.

There were two Australian couples on the trip, along with Sara, a 31-year-old volunteer teacher from the UK. She'd been teaching Zimbabwean business people how to make business plans, but had little faith in her effectiveness.

"They're developing good business plans," she said. "But there's no money to be had. There just isn't any funding."

Sara would be my tentmate. She had gotten a space in the backpacker's dorm at Kariba Breezes, and had come down from Harare on local buses.

After the meeting, I saw and ate alone.

"The gentlemen over there would like you to join them," said a waiter, pointing towards some guys I couldn't see.

I joined two of Zimbabwe's 30,000 white citizens for dinner, and they gave me a different perspective on Mugabe than I'd gotten from Fortune back on my Nomad trip.

"Mugabe is fighting for his life," said one. "He's so corrupt that he's a criminal in several countries. If he's isn't president, he'll be arrested."

Still, they loved Zimbabwe.

"It's fantastic," one said. "I couldn't live anywhere else."

"If everything falls apart here," said the other. "I'll be the last one here to turn the lights off."

I went back to my lodge. My camping neighbors were rowdy and drunk, singing and playing guitar until after two.

NEXT: Look out for that hippo! Canoeing along the Zambezi.