The Golden-Toothed Road to Samarkand

(Marie-Mail entry #33)

BUKHARA

MAY 19

I lazily opened my eyes in the morning sun. I was in one of five

converted rooms in a 300-year old Jewish merchant's house. Surrounding

me were carved wooden doors and French windows. Yeah, I thought, I could get used to this.

my hotel room

my hotel room

Then I noticed a pain in my hip and looked to discover a gross wound, where my Rohan trousers had indicated their displeasure at spending a day on the bus. The metal snaps from inside the pockets (for "expansion panels," a dubious feature at best) had dug into my hip and left an unpleasant gooey broken blister. So much for the brilliant Rohan designs. Maybe I'd go back to normal clothes and give up on technical wear.

The bathroom at Hotel Emir turned out to be just outside my room, in

the "breakfast" part of the "bed and breakfast." I was the only guest

today, so it was fine but I could foresee a situation where I'd be showering in a stranger's dining room.

Lena brought me a nice pancake breakfast, and no one interrupted my

meal with a shower. I took my time, ordering refills on the instant

Nescafe I'd accepted as a necessary evil in this part of the world.

Lyabi Hauz

Lyabi Hauz

Bukhara was pleasant, and I basked in the friendly atmosphere around

Lyabi-Hauz until lunchtime, when I realized I had a food dilemma.

The Lyabi-Hauz restaurant served meat-on-a-stick and buttery pilaf.

While I'm not a full-fledged vegetarian, I had no desire to eat a pile

of grilled nebulous meat for lunch. And my lactose intolerance put the

pilaf off-limits.

I had a look around. That was it for restaurants. There were a few

small grocery stores selling soda, and a posh restaurant serving

upscale meat-on-a-stick and meat dumplings. All the nearby hotels were

bed-and-breakfasts, so they didn't serve lunch. No problem, I though, and hiked over to the best hotel in town -- the Hotel Bukhara. They specialized in groups, and had about fifty French tourists to serve. They put me in a corner and ignored me. After ten minutes of trying to get someone's attention, I left.

"Uzbekistan -- not ready for the independent tourist." That should be

the slogan here, I thought. There was institutionalized harassment by

police, a cartel of pricey travel agents, and a lack of restaurants.

soda water machine from Soviet times

soda water machine from Soviet times

I gave up and went back to the Hotel Emir.

"Please," I said, "can you tell me where I can get some food that is

not meat-on-a-stick?"

After they were done laughing, they realized that I was serious.

"What would you like to eat?" They asked.

"Vegetables. I'd love some vegetables." I hadn't had more veggies than a cucumber-and-onion salad in weeks.

A discussion ensued, and then the 21-year-old travel agent, Flora,

took me back to the post restaurant. It was called "Saraffon," and was

atmospherically located in a converted "hammom," or public bath.

Flora had words with the cook and left me to her care. The waitress

brought me steamed carrots, broccoli, cauliflower, canned mushrooms,

and potatoes, along with the ubiquitous Central Asian cucumber salad. This may seem pedestrian, but under the circumstances I was delighted to have such gourmet cuisine.

Later, some expats explained to me that Uzbeks eat very well at home, but money is tight and restaurant culture just doesn't exist in

Uzbekistan, outside of Tashkent.

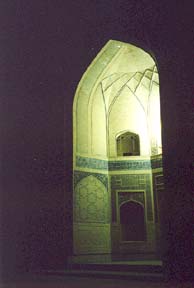

Flora took me on a city tour in the late afternoon. We visited the

sites -- the remarkable tiled medressas, the 47-meter-tall Kalon

Minaret and mosque, a few museums, a mausoleum, and the covered bazaars. Flora was sweet but had nowhere near the historical expertise that Marina had back in

Khiva. I listened politely, and much of our time was spent viewing the goods on

sale in silk shops and handicraft centers.

More interesting were Flora's responses to my personal questions. She was 21 but already being asked when she would get married. By Uzbek

standards, she was approaching "old maid" status, but wanted to "get to know herself first." She had just finished university and was one of four classmates who had managed to land a job.

MAY 20

Women brought me my breakfast. The hotel owner, staff, and travel

agent -- all were female. I noted that it was a non-threatening

environment for a single traveling woman, but still wasn't keen on showering in the dining room.

I sat in the courtyard, under the decorative arches adorning my room's

French windows, and wrote for hours. I avoided the lunch dilemma by

eating a Mars Bar (MAPC, in Cyrillic).

In the afternoon, I hiked through the back alleys to Char Minar, a

small gatehouse to a long-gone 1800's medressa. My guidebook explained

that the four colorful towers weren't minarets as they appeared to be. They were just towers. I stared at them, mystified. What was the difference?

On the way back to Husaenov Street, I ran into the man who had helped me on my first night in Bukhara. I'd spotted him earlier, greeted him, and we'd gone our separate ways. But he stopped me this time, and I knew from his manner that he'd worked up his nerve.

In a combination of Russian, Uzbek, and English, he asked me when I was

going home.

"December," I said, and further explained my mission by drawing a

circle in the air and saying "mir" (as in "world," not as in "space station").

He smiled, impressed. The he uttered a stream of unintelligible words at me followed by pointing to first me, then to himself, and then said in English, "nice dinner." I made excuses and fled.

He was a very nice man, easy on the eyes and friendly. He didn't seem slimy. I'm sure he would've taken me to a local restaurant that wasn't in any guidebook. But clearly he wasn't asking me out to further cross-cultural communication. He was asking me on a date, and that would lead to all kinds of

difficult moments as the night wore on.

It was the curse of being female -- as a man, I wouldn't have hesitated

to go to dinner. But as a man, I would never had received the invitation in the

first place.

Instead, I opted to eat alone at Saraffon. The help seated me near an expat couple from Tashkent, Michael and Rosanna, and we had a great dinner

together.

"Did the man invite you home to dinner?" asked Michael.

"No, to a restaurant," I answered.

"Then it is a good thing you didn't go. If he invited you home, you

would have met his wife and family. That is the Uzbek tradition. A restaurant

means only one thing -- sex."

Michael and Rosanna spoke fluent Russian, and as we left, the Russian

waitress told them that I was known in Saraffon as "the vegetarian." This in

spite of me eating meat dumplings minutes before.

MAY 21

Four Uzbek girls stopped me on the street. They were about 14-years-

old, dressed in school uniforms, crisp white shirts and dark knee-length

skirts.

"Hello! Where you from? You have husband? No? I have brother..."

They giggled and said goodbye.

I walked to the Ark, an old fortress past the Kalon Minaret, dodging

kids who wanted candy and pens as I walked. A little girl attached herself to me.

outside the Ark

outside the Ark

"You buy? Just looking? Maybe later? You promise?"

I promised nothing of the sort. I reflected that in about five years, Bukhara was going to be full of the hard-sell, the way Marrakech was in the early 90's (or the way Hanoi is today). I was glad to be here now, until I remembered that Hanoi has great restaurants and cheap hotels.

I had dinner with an Australian couple and then went to see the Kalon Minaret at night. I got lost first in the residential part of the old city, and then in the tourist district. Finally, I found my way back to Lyabi-Hauz after a postcard seller helped me.

"Come tomorrow to see my postcards," he said. I didn't have the heart to tell him I was leaving in the morning.

BUKHARA TO SAMARKAND

MAY 22

Flora had an unpleasant surprise waiting for me checkout time.

I knew that the haphazard bed-and-breakfast was $35 a night. The staff

had charmed me and I almost found that huge amount (in relation to the local

economy) acceptable. But what I didn't realize was that in exchange for four

hotel bookings and three city tour bookings, Bukhara Visit wanted fifty dollars.

I told young Flora that I was not happy. She said this charge was

mentioned in one of the e-mails she'd sent me. It was in the middle of a long

list of options. "Private taxi -- $65, Khiva City Tour -- $15, $80 -- car from

Bukhara-Shakrisabiz-Samarkand, Our charge is 65S per person, it includes all

booking sightseeing tour in Bukhara with entrance fees."

All I wanted was a few hotels and a few city tours, so I sent her an e-

mail that detailed precisely what I wanted and cut out everything else. I had

believed that whatever her "service" was, I had not requested it. The $65 fee,

it turned out, was $15 for Flora's City Tour and $50 for the other vague "services."

Maybe it was a language thing. I don't know. All I knew was that I

could have booked everything she'd booked for me with minimal effort. I had

foolishly assumed that it was no more expensive to have a travel agent do it.

I complained angrily and she fled. I steamed in my room. Was I going to

cry over a stupidly wasted fifty dollars? No, I was going to walk the five

kilometers to the bus stations, and by the time I got there, I'd be calmer.

It worked. By the time I got to the "mashrutnoe," or shared taxi stand, I was not angry enough to cry, just angry enough to haggle effectively. Everyone tried, as usual, to get me into a private taxi, but I refused until a nice man put me in his car with nine others.

The others stared at me, unsmiling as usual. I missed having Dominic around.

We drove 90 kilometers to Gijduvan, where everyone paid 1000 cym. I

followed suit, and then got into a "Tica" economy car bound for Navoi, the next town down the pike.

When we arrived at Navoi, I thought we'd made good time. I was almost halfway to Samarkand, and had only been on the road for an hour. I walked to the Samarkand bound cars, where things got complicated.

"Samarkand, 10,000 cym," said a driver. Yeah, right.

I negotiated, getting in and out of cars for 40 minutes. Finally, a

Tica was leaving for Samarkand. I got in with the driver and one passenger.

Another passenger joined, and sat next to me right as we were leaving.

The driver and first passenger turned out to be sweethearts. The guy

sitting next to me was kind of creepy. He leaned into me and kept asking me off-

color questions.

"Husband?"

"No."

"Children?"

"No."

He just couldn't believe this so he found a picture of a man in the

phrasebook and pointed to it, and then to me.

"Marie... husband?"

I got tired of him asking so finally I told him a lie. I said that I

had a boyfriend who worked as a teacher for the UN in Kazakstan.

The lie was multi-purpose.

1)it explained my presence in this part of the world.

2)it explained why I was alone-- my boyfriend had an important job to do.

3)by not saying "husband," I would not have to explainmy lack of a wedding ring.

Unfortunately, lies can get you into as much, if not more than, trouble

as the truth. The next questions were unexpected.

"Boyfriend...name?"

"Ummm... David." A nice name. Lots of people have it.

"Ah. Marie and David... marry?"

"Not yet."

"How old is he?"

"Um, 35." This lie was getting more and more complex.

Then he made these little motions with his hands.

"You, David..?" He twisted his hands together.

"What?" He couldn't mean what I thought he meant.

"Marie, David... sex?"

"None of your business." David was fiction, but that was beside the point.

My seatmate didn't know much English, but "no" is a universal term. So

what he heard when I said "NOne of your business," was "NOblahblahblah."

He shared his discovery with the others in the taxi. I could get the

gist from watching the conversation.

"Blahblah Marie blah blah David blah blah Almaty blah UN blah blah blah no!"

They howled with laughter at poor David, stuck living the life of a

monk in Kazakstan, no doubt pining away for marriage to Marie, who inexplicably

wanted to wait.

From now on, I thought, I'm going to say that I'm divorced.

The creepy guy left the taxi at the next town, leaving me alone with

the nice guys. We got to Tashkent, and stopped while the passenger bought us

all ice cream. I ate it out of politeness, hoping the lactose-induced

consequences wouldn't hit me until later. It turned out to be more plastic than

dairy, and I am not allergic to plastic, so all was well.

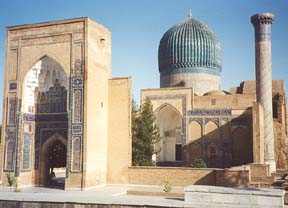

the Registan

the Registan

Finally, the driver dropped me off near the Registan. The four-hour

journey had cost me $5.50, instead of the $50-65 it would have been for a private tourist taxi.

I used my "Lonely Planet" map to find the Hotel Furkat, since Bukhara Visit hadn't bothered to provide an address. When I found it, I was immediately filled with doubt. It was old, tacky, chaotic -- in short, it looked like a five dollar Indonesian hotel, but it was $35 a night. The rooms were haphazardly furnished blocks of concrete. I decided to give Samarkand a day. Maybe I could fit a lot into 24 hours and go back to Tashkent tomorrow.

My city tour guide never showed up, meaning that my fifty dollars to

Bukhara Visit went for even less than I'd thought it would. That was okay though -- I was sick of handing out money and didn't want to pay the guide $15. I took myself on a guided tour of Samarkand.

The first stop was the Russian section of town, with the GUM department store.

Department stores all over Russia and Central Asia are the same -- big, multi-level blocky buildings, each floor housing a number of kiosks and snack bars. My favorite had been the State Department Store in Ulaan Bataar (in spite of its bag slashers). GUM was old and dark, and I left quickly.

At the bank, I cashed my traveler's checks and replenished my money

supply. At least now I could stay in Samarkand if I felt like it.

The next stop was Gorky Park (which incidentally isn't just a place in

Moscow, but just a big park in most Russian towns). I was surprised to find it

filled not just with the expected trees and grass, but also with ping-pong

tables and kiddie rides.

Then, it was on to the Guri Amir Mausoleum, the crypt of Uzbekistan's

favorite son, "Timur." I followed an Italian group in and didn't have to buy a

ticket. This self-guided city tour method was working for me -- I was covering

everything quickly.

After visits to the derelict Ak Saray Mausoleum (where I was kept away

by dogs) and the Rukhobod Mausoleum, I topped off the day with an apple juice

at a posh(ish) hotel. I nodded to the French group I had been shadowing since

Tashkent, and wandered back past the Registan -- glorious in the evening -- to

my dumpy hotel room.

SAMARKAND

MAY 23

There was still no word from the guide, so I went alone to the

Registan. It is worthy of the moniker "Central Asia's Taj Mahal." Three

enormous tiled medressas face a central square, each adorned with two minarets

or towers. The tilework is glamorous and ostentatious, and one of the medressas

features lions (a no-no for Muslims, who are not supposed to put

representations of living things in their art).

All the student rooms on the ground floors had been taken over by

shops, but I was early and the shopkeepers were still setting up. No one tried

to sell me anything, save for the guard who tried to sell me a climb up a

minaret.

town market

town market

I visited the lively, chaotic town bazaar before returning to Furkat

and checking out. I had done well in my 24 hours in Samarkand, and was ready

for some TLC from the friendly staff at Hotel Orzu.

A taxi took me to the bus station, where I bought a space in a group

minivan headed to Tashkent bus station. Three and a half hours later, I had my

eyes peeled for policemen as I boarded the Tashkent Metro.

TASHKENT

MAY 24

I sat in Reception and read the newspaper.

"Three Tajik migrant workers were killed by land mines at the Tajik-

Uzbek border. They were crossing illegally to avoid extortion by border guards."

Official corruption in Uzbekistan was not limited to the police; it was

endemic. I was glad that MariesWorldTour.com had voted to let me use a Lifeline

and take the plane to Moscow.

I visited the huge Chorsu Bazaar in the old city. Its massive size and

colorful businesses were a reminder that this was indeed Central Asia, and not

the European city that Broadway resembled.

an unfortunately named detergent

an unfortunately named detergent

MAY 25

Having learned my lesson about the Tashkent Metro (see "Tashkent

Shakedown"), I caught the bus to the town center to go to the Sheraton.

I was in the market for a paperback book to read, and was surprised

that the Sheraton did not have books in its giftshop.

The concierge helped me. One thing about being a westerner in a foreign

country is that most posh hotels will assume that you are staying there, and

will answer your questions and let you use their toilets!

He sent me to a book stall near the opera house. "They have every kind

of book," he said.

Among other things, they had a lot of computer books, the "Lord of the

Rings" in Russian, and a small selection of English books. I chose a book of

short stories for "Advanced" readers, and went to Amir Timur Park to eat my

lunch.

High school students were everywhere, the girls dressed in a

unique "evening-wear" style that made them all look like they were about to go

clubbing in a big city, or just like they were tramps. I stared for a while,

trying to work out what it was about the slinky gowns that made them look so

much more suggestive than they really were.

Finally, I realized that it wasn't the clothes. It was the girls. A

steady diet of meat and mayonnaise creates a unique shape, and I was

surrounding by teenage girls with big butts. I was a bit shocked at myself for

noticing, and appalled that I had bought into western pop culture's notion that

thin is in, but was happy that for once my own behind was small in comparison.

NEXT: Finally on to Moscow! The Kremlin, Red Square, and the freezing cold.