Party Bus to Bukhara

(Marie-Mail entry #32)

KHIVA

MAY 17

The taxi driver had tried to tell me, but I stubbornly refused to listen.

"Hee-vah," he said, dropping the K in the local style. "One day, no more."

Taxi drivers know these things. They spend a lot of time with tourists, and are well-versed in their needs. I had cynically assumed he had just been trying to wrangle me into signing up for his day trip to nearby Karakalpakstan, and turned down his offer in my excitement over the remote ex-Khanate capital.

My guidebook, or more accurately, the photocopies I was carrying around, agreed.

"Khiva is an odd place... it's a squeaky-clean official city-museum... you need imagination to get a sense of mystique, bustle and squalor," wrote an unspecified "Lonely Planet" author. Then, Dominic and Esther, a Swiss couple staying at Hotel Arkonchi like I was, described the museums as "a few brochures under glass."

Khiva is inhabited, but only outside of the tourist area. The average tourist's interaction with the local people consists of asking for the bill in the hotel.

In less than an hour, I had seen Khiva, with is turquoise domes and tall, tiled minarets.

The Uzbek women souvenir sellers all stared at my legs as I walked around. They didn't smile, nod or look surreptiously. They just stared.

I beat a hasty retreat back to my rundown room at the Arkonchi, where I examined my legs. They were covered to just below the knee, like the locals' legs. My pants were not too tight (my last meeting with the laundry having been back in Almaty). I had no unsightly bruises.

mosque and minaret

mosque and minaret

"It's because you're wearing trousers," explained Dominic. "Women don't do that here."

I changed into the long, black skirt that Ex Officio had sold to me for a ridiculously low sponsorship price. People still stared after that, but they also smiled.

I sat outside my room, in the overwhelming desert heat, and read about Khiva. My room, and the entire hotel, was in need of an upgrade. "Central Asia Overland" had described Hotel Arkonchi as great, but they may have visited a long time ago. They also could have been drunk when they wrote that.

Arkonchi may have been great once -- it had the perfect location, a helpful staff, and a courtyard filled with traditional Uzbek tea platforms -- but it was not great within the last decade. I mentally classified it as "acceptable," because the doors locked and the toilets worked. The showers also worked, but the water was ice-cold except in the heat of the afternoon.

The "star" standard used throughout the world didn't apply to my trip. Instead, I had developed my own rating system.

"Appalling" (smells, dubious plumbing, dirty)

"Gross but okay for a night" (one of the above)

"Acceptable" (wide range)

"Posh" (like a Motel 6 in the States)

"Really Posh" (like a Motel 6 with a hairdryer)

"Acceptable" hotels were sometimes knocked down a few notches due to their expense. I reflected that it took a lot of nerve to charge $25 a night for a tiny, old room with a cold shower, but the Arkonchi did include all meals. That redeemed it somewhat, as the Arkonchi, by default of being the only place in town to eat, was the best place in town to eat.

Unfortunately, Arkonchi and all eating establishments in Uzbekistan specialized in dishes covered in dill. I am allergic to nineteen things, and dill is in the top five, with a lethal rating just below dairy, soy, seafood, and tobacco. I'll spare you the gory details.

West Gate

West Gate

Marina, the guide "Bukhara Visit" had booked to take me around Khiva, showed up at 11. I had just been viewing the day bleakly, wondering what to do in Khiva now that I knew there was nothing to do in Khiva. She showed up, confident and friendly in shorts and tank top, and completely changed my opinion of Khiva.

medressa

medressa

She took me behind the brown walls and explained the meaning of the intricately tiled mosques. She showed me the Khan's fortress, the prison and public square, and the serene, shady Juma Mosque with its 218 wooden columns. Khiva came alive in context and then Marina explained a thing or two about Uzbek culture.

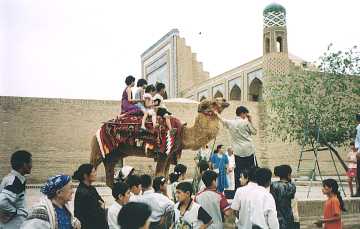

Michael the camel

Michael the camel

"To be Uzbek is to be Muslim," she said. And that is why she is often regarded with suspicion. She is half-Uzbek, half-Russian, and one of the nine percent of Christian Uzbeks.

Uzbek Muslims were unique in their style of devoutness. Seventy years of Soviet-enforced atheism could not be erased overnight, and while the current Uzbek vogue was to profess religious belief, there seemed to be a very relaxed adherence to traditional Muslim values.

Khiva skyline

Khiva skyline

For example, Uzbeks don't eat giant hams because Muslims don't eat pork. But they scarf down loads of salami and Spam-like sausages and don't seem to notice anything odd about this. Perhaps it is because religion in Uzbekistan is laced with elements of Zorastrianism and atheism, making it a hybrid religion with nebulous rules that are open to interpretation.

city walls

city walls

Many Uzbeks are concerned about religious zealots, as Afghanistan is their immediate Southern neighbor. The Bolsheviks had forced literacy onto the Uzbek women, and the veil off of them, and no one is interested in turning back those clocks!

Marina told me a story about when some conservation Muslim men had tried to reintroduce the veil.

"The women politicians said, okay, but you must follow tradition as well. In the past, men shaved their heads and wore pantaloons. And that was the end of the veil."

And to my surprise, Marina was divorced. She married late for an Uzbek -- at 22 -- and had one child.

"My marriage was arranged -- by me," she explained. "I was tired of being asked why I was not married. I wanted to prove I could do it."

"Is it difficult to get divorced in Uzbekistan?" I asked.

"No. We lived apart for two years, and then went to a judge. We had to sign papers. That is all."

"And does the child always go with the mother?"

"Always. Unless the mother is an alcoholic or drug addict."

We passed a wedding procession, the young bride decked out in white and flowers.

minaret

minaret

"Is that traditional?" I asked, doubtful.

She laughed. "No, that is from Russia. White is the color of mourning, so later she will change to colorful Uzbek silk before going to her new house. In the car. Trust me, I have seen this. I was the maid of honor and the bride changed in the car.

At the end of the tour, Marina thanked me for listening. I told her she was an excellent guide, and asked her when the buses left Urgench for Bukhara.

city gate

city gate

She didn't know, but said she'd find out and call me later. This was great -- every other Uzbek person in the tourist industry had said the bus took forever and was not suitable for tourists. Tourists in Uzbekistan took private cars, at $65 a pop. Tourists should NOT take the bus!

Marina called me later, as she had promised.

"The buses leave at noon, but you must get to Ahk-Yol -- the bus station -- at ten to get a seat."

Dominic and Esther, meanwhile, had discovered that local minibuses bound for Urgench left from the North Gate. They were game for a bus ride, and over dinner topped with dill at Hotel Arkonchi, we planned to travel together to Bukhara.

Juma Mosque

Juma Mosque

KHIVA TO BUKHARA

MAY 18

Dominic, Esther, and I walked to the North Gate, our luggage hanging off our backs. I was lucky -- my small daypack was much easier to carry than their full-sized backpacks.

At the North Gate, there was a row of public minibuses. We piled into the Urgench one (glad we had learned some Cyrillic), and for 175 cym each, got to ride all the way to the Ahk-Yol bus station.

The bus appeared to be a retired German bus, and initially we had high hopes for air-conditioning. We laughed at ourselves later, sweating in the unventilated heat. We each paid 500 cym -- $1.31-- for seat reservations. The other passengers milled about the platforms and stared at us.

our chariot

our chariot

Suddenly, I discovered the value of traveling with others.

The Uzbek men liked Dominic, and they approached him to have a chat. Esther and I were occasionally addressed, but mostly Dominic was the star of the show.

A small boy approached, using burning weeds to bless possessions in exchange for pocket change. Dominic paid the kid to bless our packs.

The locals found this hilarious. The ice melted. The men asked where we were from, and a woman pointed to my sewn-up messenger bag and looked inquisitive. What had happened?

I mimed someone slashing my bag. She look horrified and asked a question that I took to mean "was it all okay?" I mimed yanking the bag close to me and gave her the okay sign. She looked relieved and turned around to share my story with the others, who all gasped as suitable points in the narrative.

Dominic, meanwhile, was fielding the men's discussion forum. After explaining where we were all from, he was asked for a paper and pen. Someone produced one, and an Uzbek man proceeded to draw his artistic interpretation of the United States.

"U.S.A." he said, scribbling out an oblong blob.

"Mexico." He drew a new blob, immediately south of Texas.

"Ummm..." he paused, thought and started again.

"Colombia!" He announced, drawing in one last blob.

I giggled, but before I could inform him of the existence of Central America, he got to the point of the map.

He drew a plane and several arrows between Colombia and Miami.

"Cocaine," he said triumphantly.

The crowd laughed. I forgot about giving a geography lesson and laughed in spite of myself.

The stage had been set, and everyone joked non-stop. Men laughed, women giggled, and us westerners smiled politely. We knew that fun was the order of the day, but more often than not had no idea what the joke was.

My seatmate spoke a little French, and I still had my trusty Russian phrasebook, so we were all able to communicate in a stilted manner.

The bus started. We all paid our fares of 2500 cym each.

A group of men took up residence in the back of the bus.

"Dominic, Dominic," they called.

Dominic went back to join them, leaving Esther and I discussing his "smell" with the women.

"Dominic... parfum?" asked one.

"What? No." Dominic wasn't wearing perfume. We were both confused.

One woman looked up "sweet" and "smell" in the phrasebook. Dominic smelled sweet to the Uzbek women.

"Name... parfum?" They wouldn't accept our response that he was perfumeless. Finally, one of them brought out a piece of paper to write down the name of his mysterious scent.

Dominic wrote "Nivea," the brand of soap he had used that morning, and ended the controversy.

"Dominic, Dominic!" The men called to him to return to the back-of-the-bus club.

a happy bus

a happy bus

Esther and I, at first envious of his position among the locals, eventually took to pitying him. We were left to read our books and nap, while he was unable to turn off the charm for even a minute. The lack of a common language didn't worry the Uzbek men. Everyone had the common language of mass consumerism and pop culture. We laughed as they named every European brand of clothing, cars, and musical group. They named every country in Europe, and then every country in NATO, every country in Central Asia, and ever album ever made by Madonna. (Okay, I made up the last one.) They named the Nexia and Tico, both Uzbek cars made in conjunction with Daewoo.

Finally, the bus stopped for lunch.

The Uzbeks bought pilaf and bony grilled meat, while Dominic, Esther and I sat alone with our Hotel Arkonchi-packed lunches.

"Phew," said Dominic, exhausted from the morning. "This is really traveling."

Then, as an afterthought, he added, "but I will be glad when we get to Bukhara."

The Uzbeks resupplied their water bottles from a pump. Esther and I braved the toilets out back, and the locals were as dismayed as we were by the stench. The Uzbek women carried toilet paper, unlike women in other Muslim countries. The Soviet influence had left a hybrid of western and squat toilets, some with water and some with paper, and some, as in all countries, with nothing at all.

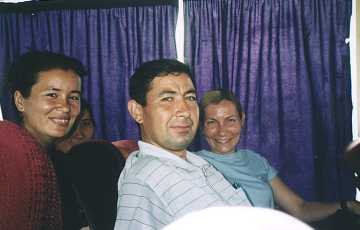

my seatmates

my seatmates

"This lady is from U.S.A." announced a gold-toothed woman as we reboarded the bus. Gold is plentiful in Uzbekistan and is regularly used to cap or fill teeth.

We motored on. The two women sitting behind me conveyed that they were mother and daughter. The man sitting next to me was 30, but looked 50. I made this mistake frequently in Uzbekistan. It must've been the bright sun that aged people so quickly.

We reached the Turkmenistan border. The road cut a corner of Turkmenistan, due to the random but frequent border redrawing during Soviet times. There was no other road and no other way to Bukhara.

Border guards had a look at us, and everyone was nervous and silent. No one was hassled and we moved quickly across the ten minute stretch of highway, stopping again to re-enter Uzbekistan. The Uzbek guards took our foreign passports and disappeared.

After ten minutes, the bus driver got tired of waiting. He started the bus and inched it forward. Dominic, Esther and I exchanged glances -- what about our passports?

"Passport!" screamed about twenty of our new friends. The bus driver laughed and continued moving.

Just then the guard came running back, chasing the bus. He handed the passports to someone in the front and we were on our way. It had been part of the driver's strategy to hurry the guards.

Having made it back into Uzbekistan, everyone relaxed. A swarthy middle-aged fellow popped an "Abba" tape onto the P.A. and our passports were studied thoroughly as they were passed back through the bus.

cooks at the rest stop

cooks at the rest stop

I found myself explaining that I had no husband or children, but I did have a plant, to the incongruous jubilant sounds of Sweden's most celebrated pop stars. It was great fun, but all three of us were relieved when the bus pulled over in darkness, to leave us by the side of the road in Bukhara.

We negotiated with the taxi drivers that appeared our of the night, and selected the one with the best offer of $2 for three of us. The other taxis vanished, driving off to seek other fares. Then, our driver pulled a fast one.

He put Dominic and Esther's packs in the trunk -- locked them -- and drove us about 30 seconds. He stopped and asked for a pen.

He wrote "50 km," and said "Bukhara."

"No," I said. The bus wouldn't leave us 50 kilometers from Bukhara.

He insisted. He wanted to renegotiate the fare. I got out. Dominic and Esther did too.

I motioned for him to open the trunk. The bags were in there, and seemed to me that we would have better negotiating power if he did not have them hostage.

He resisted, but then relented as I became more demanding. I spotted a police station across the highway. We crossed over and approached a patrolman. The driver started to talk but I shushed him.

"How far... Bukhara?" I asked, pointing to a phrase in the "Getting Around" chapter.

He pointed to the ground. We were in Bukhara.

"Lyabi-Hauz?" I asked. That was the center of the old city.

He took the pen and wrote "28km." We went back to the car, agreed to a five dollar fare, and put the luggage back into the trunk.

The driver drove 21 kilometers to the Bukhara bus station and stopped again. Now he wrote "15km" and said "Lyabi-Hauz."

"Bullshit," I said. "It's five kilometers." I held up five fingers. The photocopies I was carrying -- one set from "Lonely Planet" and one set from "Central Asia Overland" agreed on that point.

Dominic and Esther were tired of this game. So was I. But while I was for getting out and taking our chances with finding another taxi or walking, they had a lot more luggage than I did and just wanted to pay the man.

"NO." I pointed to the "15km" on the paper and refused to negotiate or to get out of the taxi.

Dominic took over, negotiated a new priced of a few more dollars, and told me he'd pay it. I agreed, but registered my dissenting vote. Paying for this kind of behavior only encouraged it.

I simmered the last five kilometers to Lyabi-Hauz, but found the time to look up the Russian words for "I don't agree" and "thief." As soon as the luggage was out of the trunk, I lost no time in using my new vocabulary words, to the surprise of the driver.

We stalked away. Our 15-minute taxi ride had cost the same as a nine hour bus ride for one. And none of us knew where our hotels were.

Dominic and Esther had booked through Sportur (sport@airam.silk.org) -- an agent they recommended highly -- and were hunting for Pushkin Street. My agent hadn't bothered to give me contact details, but I had looked up the address on the internet and was headed for Husaenov Street.

We inquired at the Lyabi-Hauz fountain. A group of women were chatting in the park, and pointed us both in separate directions. They assigned me two teenage boy escorts.

Parting with Dominic and Esther was awkward, after our intense shared experiences of the day.

"Wow, Mah-ree," said Dominic. "You were really tough with that taxi driver."

He was right. I had developed skills of negotiation and bravado over the last five months.

"But it didn't help," I laughed.

"Maybe we'll see you around."

"Maybe."

They walked east and I walked south, following the two boys.

The old city of Bukhara was a confusing maze of tiny dirt pathways. There were no street signs, and no one knew which street was Husaenov. Ten minutes of disorienting dirt alleys later, I arrived back at Lyabi-Hauz. So did Dominic and Esther. We all laughed and tried again.

The next time this happened, it was less funny. I had inquired at "Sasha and Son" guesthouse (THEY were well-marked!) and at the security guard post at the bank. The two boys were no help, so I had left them, assuring them that I would work it out.

Everyone kept pointing me in the same direction, so I knew I was close, but saw no evidence of "Hotel Emir" or Husaenov Street.

Finally, exhausted, I walked into the open-air meat-on-a-stick restaurant at Lyabi-Hauz. I must have seemed desperate, because everyone jumped to help.

"WHERE is Hotel Emir?" I begged.

No one knew, but a tattooed Russian worker there knew what to do with a desperate tourist. He took me to Tourist Information.

It was 11 p.m. by now, and it wouldn't have occurred to me to go to Tourist Information (http://www.bukhara.net/bicc.htm), especially since the hours were clearly marked at 10-6.

The Russian pounded on the door until it was opened from within. The people who worked at Tourist Information kept late hours, as it was also a resource center with reference materials and internet access.

The info guy called the hotel, and a blond woman named Lena came to fetch me. I thanked my saviors, and followed Lena back to a short alley I had walked down four times.

One of the blank, plain doors in the wall housed the Hotel Emir. I was too tired to explain that an address or sign on the door might be helpful, and collapsed into my room. As I drifted off to sleep, it vaguely registered that my hip hurt, and that there was no bathroom in my room.

NEXT: Meat-on-a-Stick! A stupid loss of fifty dollars! The Golden(ish, sort of) Road to Samarkand.