Blues and the Flu

XI'AN, CHINA

APRIL 22

Self-pity was the order of the day as I moped around Xi'an. I didn't know which hotel room belonged to Yancey and Michael, and had stared bleakly at the "do not disturb" signs on the various doorways before giving up and going alone to a nearby shopping mall to hunt down coffee.

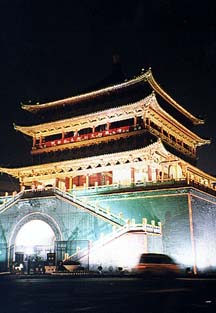

Bell Tower

Bell Tower

My birthday adventures included being frightened away by the shopping mall toilets full of squatting women in doorless stalls, sulking my way around the ancient city walls, and accidently stumbling on an alley devoted solely to various types of strange sausages. Finally, I went to the self-imposed exile of my hotel room, where I ate peanut butter and watched "Batman Adventures" in Chinese.

City Wall kite festival

City Wall kite festival

The Scarecrow was captured and Gotham City saved, but I was still feeling the lonesome birthday blues, when the phone rang at six. It was

Rob, who was terribly ill but had managed to scrape together a small crowd for a "surprise" dinner.

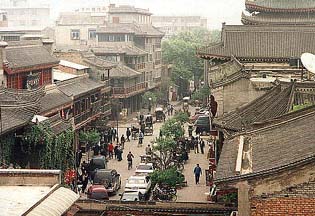

streets of Xi'an

streets of Xi'an

Rob didn't bother with any clever pretenses. I knew I had turned 35, he knew I had turned 35, and I knew he knew.

"Meet downstairs in 20 minutes," said Rob.

I ran into him at the elevator, and he shoved a cake-shaped box into my hand. I felt like a dork carrying my own surprise birthday cake, so in turn I handed it off to Michael.

It was raining out, and no one had bothered to keep an eye peeled for a promising restaurant. Rob had an excuse -- with his illness, he had barely managed to acquire a cake. Everyone else looked expectantly at me -- we're hungry, where should we go?

I wanted to be coddled by a few sympathetic friends. Playing organizer to a group of mostly strangers was not on my birthday list. It was

pretty lame that the responsibility was thrown to the birthday girl, and I had to consider budgets to boot. Some members of the group were spendthrifts and would have been unhappy if I'd asked for a meal I might conceivably enjoy, such as pasta or curry.

I got my guidebook. It listed few restaurants, all of which were some rainy distance away, and none of which were appetizing. Rob's "Intrepid" handout listed the restaurant in our hotel as worth trying, so we did.

The hotel restaurant was a point-and-pick a la carte restaurant. Everyone stood around uncertainly -- what was that strange food and

what if we don't like it? In the end, Yancey and I got fed up with the uncertainty and pointed to several dishes at random. Anything was better than waiting for everyone to make up their minds.

Marie's World Day Tour?

Marie's World Day Tour?

The waiters kept bringing out dishes. Some of them were dishes we didn't even know existed and certainly hadn't ordered. One waiter brought five pineapple juices, instead of the one I'd ordered. Sick Rob had to jump in and draw the line.

"No more food," he said to the waiters. "ENOUGH." He said "stop" in Mandarin, and finally the food quit coming.

A familiar tune started up on the p.a. system and to my great astonishment, a cake came out of the cake-shaped box. It was inscribed

with "Marie's World Day Tour," an obvious mistake that combined "Marie's World Tour" and "Happy Birthday," but Rob had decided to let the inscription stand. I was glad he did. It was an excellent physical representation of the most haphazard birthday I remembered having.

Someone lit a few candles and everyone sang. Then the song played again. Everyone sang. And again. By the six or seventh time, I was ready to scream, but the group good-humoredly went along with the repetition.

I hadn't received a card or a gift (or even an e-mail as it was still April 21 at home), but the hotel made up for the lack of commemorative

gestures with a surprise -- they presented me with a miniature porcelain baby statue. It was a baby boy with his diaper missing. I asked Yancey to take it home for me. I briefly considered never getting a home again so that he would be stuck with it.

Finally, we all (yes, including me with my barely contained disgust) divvied up the bill and said our goodbyes. Yancey and Michael took me

upstairs to the hotel tea house. I ordered "fruit tea" and it turned out to be warm orange juice. Yancey watched sports on the bar television while Michael told me about their fantastic day.

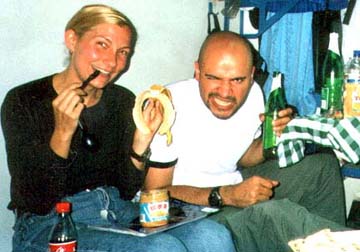

birthday dinner

birthday dinner

They had been wandering through gift shops in the Muslim Quarter, and stopped in one to look at the miniature Terra Cotta Warriors and

intricate pottery. The store owner had said, "psst, hey, wanna buy a flag?"

"Huh?" The guys expressed interest. If something was this hush-hush, it must be interesting.

The store owner went into a back room, dug around, and came back with a U.S. flag.

They had excused themselves, confused and laughing, turned a corner and accidently stumbled into the mosque without paying the admission fee.

They'd played pool with an oblong que ball, and had the pleasure of using the worst toilets yet. They'd devised a buddy system, where if one was not out in a minute, the other would run in and drag him out.

"It was 9.9 on the Stench-O-Meter," declared Michael, who was known to double-knot his shoes to avoid any chance of a lace dragging through

the nebulous puddles in the men's room.

They both went to bed and I went back to my room to eat more peanut butter. Another birthday over. What a relief.

APRIL 23

XI'AN TO BEIJING

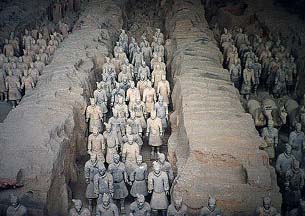

Lucy, our local guide, took us in a minibus to see the Terra Cotta Warriors. They're ancient (2000 years old) and life-sized, which means

quite a bit smaller than an average American. Each is unique, because all are based on

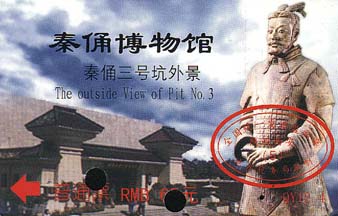

Terra Cotta ticket stub

Terra Cotta ticket stub

real soldiers of the time. They were made to go into the afterlife with the emperor, in the same way that Egyptian pharaohs were buried with slaves that they might need later. But the Chinese had the courtesy to bury ceramic figures instead of living people. We were able to visit three giant "pits" of sand-colored soldiers, and there are possibly more as excavations still continue.

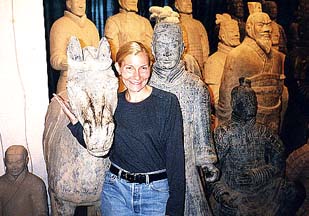

Terra Cotta Warriors

Terra Cotta Warriors

A few people had warned me that I would be disappointed by the Terra Cotta Warriors. Perhaps due to my lowered expectations, or perhaps due to the vast number of amazing figures, I was awed. To add to my enjoyment of the site, we saw a short film. I got to watch a young, attractive woman, on the arm of her boyfriend, drizzle spit onto the floor of the movie theater.

Terra Cotta Warriors

Terra Cotta Warriors

Lucy took us back to the hotel to fetch our luggage. En route, we were caught in a traffic jam, which gave us a lot of time to pick Lucy's brain about China.

Not with the real thing, Marie in the souvenir shop

Not with the real thing, Marie in the souvenir shop

Lucy told us that education in China is free, and that health insurance is not. The best health insurance is the most expensive. Cars must undergo periodic inspections, and driver's must train and pass a test to get a driver's license. KFC is everywhere, because KFC has been in Xi'an for a decade, whereas McDonald's is a relative newcomer. There is no McDonald's in Xi'an. The locals love KFC, though.

Lucy also told us a lot about the Chinese media, without actually realizing it.

"Is it true," asked Lucy, "that in the U.S. there are many guns? Many drugs? Much divorce?"

She'd obviously been reading too much "China Daily."

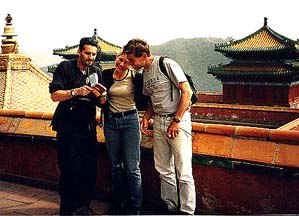

Marie and Yancey. Photo by Michael.

Lucy left us at the train station, where we had "hard sleepers" booked for the overnight trip to Beijing. The hard sleepers are grouped into

six berths per section. On this train, unlike the Hong Kong train, the hard sleepers were open, without compartment doors. It is less secure, but far less claustrophobic. And on this trip, no one played mah-jong.

Emma and Yancey on the sleeper train

I had learned by now when to avoid the train toilets. I had christened the times just before bed and just after sunrise as the "twilight

hawking" and the "morning hawking," after a method of communication employed by a certain number of white and black-spotted dogs.

BEIJING

APRIL 24

Intrepid's China infrastructure had been nearly flawless to this point, but it finally slipped up in Beijing.

Post-morning hawking, we got off the overnight train. Rob warned us that getting to the "Conference Hotel" could be difficult because it

was not the hotel that Intrepid groups usually stayed at, and he wasn't quite sure where it was.

Everyone was prepared to get lost, but no one was prepared for the nonsense that ensued as we attempted to get transport. Rob had a budget

of 80 yuan to get us from the railway station to the hotel. Intrepid knows local costs and budgets accordingly.

Every local transport and adventure travel group I've even been with does this. They know the real rates, not the tourist rates. Leaders are expected to pay local prices and are often paid local wages (which is why I always tip leaders, who deserve at least one of my dollars a day).

In theory, it's a great, ethical policy. In practice, it's flawed. Every leader and tourist stands out, and often local prices can be had

only after extended haggling and excessive energy.

Rob performed said haggling like a madman, as he attempted to get us a minibus to where he more-or-less knew the hotel to be. Shenanigans

ensued, and one enterprising fellow cut a deal only to attempt to load all thirteen of us and our packs onto a public city bus during rush hour.

Some of us went to hold places in the long taxi line, while Rob negotiated with drivers for half an hour.

Finally, he scored. A city bus driver anxious to make some cash on the side loaded us onto his dusty bus. He drove slowly into the morning

traffic, through a sea of Volkswagen Santanas (that's VW "Fox" in the US). The bus was giant, old, and emitted a terrific high-pitched squealing when at rest.

The driver dropped us off by the youth hostel, and we walked the last few blocks. I had been cranky at the railway station -- Intrepid

transfers groups through Beijing several times a month so they should have transport arranged -- but the ridiculous bus ride had perked me up. The hotel was exactly where Rob had thought it would be so we all showered and went our separate ways.

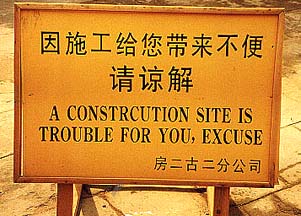

Many interesting translations in China

Many interesting translations in China

Emma, Tim, and I headed by taxi to the Mongolian Embassy. They were following my Trans-Siberian route a week later, and had coincidentally

used the same Australian booking agent. Yancey was going with me as far as Mongolia, but he'd acquired his visa in New York.

The Mongolians issued my visa on the spot, and we got into a taxi to pick up our railway tickets at the China International Travel Service

office.

Beijing is a planned city, and our taxi drove us along attractive, well-policed, wide boulevards. But Beijing had none of the vibrant, chaotic energy of Shanghai. The difference between China's two biggest mainland cities can best be compared to the difference between Washington DC and New York City. Without the corresponding crime statistics, of course.

We stopped at Starbucks, where I swiped a pile of napkins. The Chinese are stingy with their paper products, to the point where if napkins

came with meals at all, they were tiny half-napkins. The energy spent slicing up napkins showed clearly the low cost of human labor as opposed to the cost of materials. And toilet paper, even in tourist hotels, was carefully rationed. It was common to run out. Yancey had big plans to advise "Charmin" to invest in China. And "Lysol."

The lack of toilet paper wouldn't be so bad if there was a water supply, like Indonesia's mandi or India's faucet and hose. But there

never was. Chinese toilets were stinking doorless closets, featuring flushing squat toilets but no water source and no paper. They are, I believe, the worst toilets in the world, as even the tiniest, poorest village in India supplies a jug of water next to its hole in the ground toilet.

"Why," we had asked one of our guides, "are Chinese toilets so appalling? The sidewalks and roads are good, the hotels have hot water

and reliable electricity. For God's sake, what's with the toilets?"

She'd looked mystified at our concern and simply replied that little time is spent in the bathroom, so toilets are not important.

China will have to improve its toilets if it gets the 2008 Olympics. Billboards all over Beijing advertised "Beijing 2008." Newly

constructed handicapped-accessible sidewalks, featuring ramps and raised dotted pathways, run the length of the main drag, alongside Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City. China was working hard to get the Olympics, and if it doesn't, will be hotly embarrassed.

Or will just chalk it up to anti-China sentiment in the west, ignoring the human rights issues that the west will no doubt be expressing

concern over.

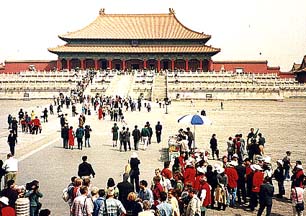

Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen Square

I left Tim and Emma at Tiananmen Square and caught the subway to FedEx. My mom had sent me a birthday gift and I needed to track it down.

International FedEx, I had discovered back in Bangkok, is reliable but a pain. Each country has its own set of import/export rules and I never had a clue what they were. I spoke to Customer Service, sent various faxes, and spent ages at hotel reception trying to communicate that a package would arrive for me and they needed to accept it. After initial confusion ("you send a package?"), they seemed agreeable, so I talked Michael and Yancey into joining me for Thai curry, leaving all thoughts of manifests and pro forma invoices aside for the evening.

APRIL 25

Linda was our local Beijing guide, and she took us to the Forbidden City by public bus.

Linda, Lucy, George -- these were not the real names of our guides. They were English equivalents of Chinese names unpronouncable to most

westerners. It's the same as when Russians call me "Masha," or the French calling a Steve "Etienne."

We entered the Forbidden City through an archway under a giant portrait of Mao, and followed the crowds of Chinese tourists.

Marie and Mao

Marie and Mao

Many of the female tourists were adorned with an alarming fashion trend -- caucasian-flesh-colored nylons, covered by flesh-colored

anklet socks. It reminded me of the lightening creams many Asians purchase to alter their skin colors.

"Linda," I asked, motioning at a nearby heinous example of this trend, "why do they wear those stockings?"

She looked at me blankly. "Because they are skin-colored."

Yeah, I thought, if you're Morticia Adams slathered in foundation -- and you're dead.

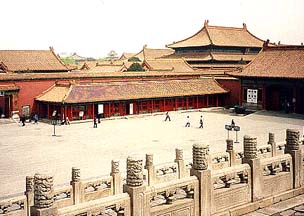

Forbidden City

Forbidden City

Linda told us that modern China consisted of 34 provinces, including Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. More than a few eyebrows were raised, and someone muttered, "that makes 33 then," but Linda pretended not to hear.

Hours of fighting crowds while touring wives' quarters and emperor's throne rooms left me exhausted. I left early, to buy Peking Opera

tickets for Michael, Yancey, and myself. It took me twenty minutes of rapid walking to leave the Forbidden City -- the compound was enormous. I crossed heavily-policed Tiananmen Square, taking care to avoid the firetrucks parked at the edge (protesters had been setting themselves on fire lately) and found the theater.

Forbidden City

Forbidden City

Tickets were 150 yuan -- that's $19, too much for an hour and a half of the same clanging and shrieking that I'd seen a dozen times at the

Chinese Cultural Center in New York. And I didn't want to spend that much of Yancey and Michael's money without first consulting them.

I took the subway to the Xiushui Market. I was going to Siberia and needed something warm. The first stall I saw had bulky, warm "North Face" parkas.

"How much?" I asked, pointing to a yellow one with a 945 yuan price tag.

"700," replied the seller. "Real North Face. Real Gore-Tex."

Yeah, right, I thought.

"Do you have a fake one? I need something cheap," I said.

He laughed and laughed. My reply must have been unique.

"Try it on. Are you small?"

I did and I was.

"I still need cheaper. What do you have for 100?"

"Okay, 350," he said.

"No. I need a cheaper coat. Are those cheaper?" I pointed to the same coat in a different color.

"Okay, how much you pay?"

"120."

"250."

"150 is my best price."

"What is your last price?"

"I told you, 150."

The deal was made. Yancey and Michael both liked my new coat so much, they decided to go back to the market with me and buy coats instead of

seeing the Peking Opera.

Peking Opera Blues?

Peking Opera Blues?

We left our "real" North Face coats in the Conference Hotel and went to the Night Market, a set of alleys near a modern shopping street.

The atmosphere was carnival-like, as hawkers yelled at passerbys to try their specialty of the house.

Night Market

Night Market

Frog-on-a-stick featured prominently at many stalls, but Yancey and Michael opted for a shapeless meat-on-a-stick, while I ate rice noodles. Nearby teahouses competed for business, using free outdoor Peking Opera as hooks.

Contented Salesman

Contented Salesman

"I am so glad we got coats instead," said Yancey as he watched a costumed actor screeching across a rooftop. Chinese opera is not for

everyone. I'd say it's the opposite of an acquired taste. At first it's interesting for the colorful scenery and acrobatics, but eventually the clanging of the gongs and shrill singing is just annoying.

Yancey, Michael, and meat-on-a-stick

Yancey, Michael, and meat-on-a-stick

The guys were exhausted from spending a fascinating day at the right-wing war museum, so we walked home early, passing police headquarters

en route.

Squads of police drilled in front of the building, preparing for the May Day Parade. They were marching, running, and doing kung fu in

formation.

One regiment was practicing on the side. Michael referred to them as the Sweathogs, because they were laughing, clowning around, and clearly

remedial marchers. I created chaos in the ranks, as they all stole glances and whispered to each other.

"In my next life," said Michael. "I'm coming back as a blond woman. And I'm visiting China."

"It isn't real," I offered, but he didn't alter his plan.

CHENGDE

APRIL 26

It was a four and half hour ride from smoggy Beijing to smoggy Chengde. Carl amused us with a story of a terrifying sight he'd spotted in Beijing.

"I was walking from the hotel to Tiananmen Square," he said. "Three Chinese businessmen were walking in front of me. Suddenly, two scrappy, filthy kids ran out of the bushes and jumped on one man. His friends ran away! The kids wrapped themselves around the man and wouldn't let go until he gave them money, and then they disappeared back into the bushes."

This was truly a unique (and frightening) way to make a buck. I ranked it on par with the Delhi shoeshine boys who squirt brown goo on shoes and follow it up with, "sir, you have shit on your shoes."

The bus ride was harrowing, with several seemingly near-misses. I tried to convince the others that fast, laneless driving was by no means unique to China, but even Rob admitted later that he'd been nervous.

Chengde was, not surprisingly, a dusty, smog-ridden town, filled with modern, squat, functional concrete buildings like those all over China. It's primarily a less-touristed springboard from which you can visit the Great Wall, but Chengde has several unique temples that have earned it a designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We visited a few of these temples, after the usual, hopelessly confusing group meal, filled with uncertainty and misunderstanding.

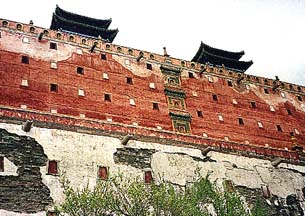

Putuozongsheng Zhi Miao

Putuozongsheng Zhi Miao

The first temple, the Putuozongsheng Zhi Miao, was a smaller replica of the Potala Palace in Tibet. The second was Pule Si, a working temple with prayer wheels, prayer flags, wafting incense, and an enormous sculpture of a many-armed deity. Both were atmospheric and remarkable to visit.

Pule Si temple

Pule Si temple

prayer flags at Pule Si temple

prayer flags at Pule Si temple

Unfortunately, I had acquired the group's hacking cough, and the first 24 hours were filled wtih headaches, exhaustion, and a sore throat. I

begged the night off, and sat in my room watching "The Smurfs" in Chinese, interspersed with commercials for "Beijing 2008." A soap opera came on later, in which all characters wore "North Face" gear.

Rob shows Marie and Michael a thing or two

Rob shows Marie and Michael a thing or two

Michael knocked on my door at half past nine and lured me down to the hotel rec center for some "ping pang" with him, Yancey, and Rob. The

rec center looked more like a bordello than a rec center, with a main desk and a warren of tiny rooms behind closed doors. The entertainment options listed included karaoke, mah-jong, and "ping pang," according to the menu.

The athletic Michael soundly trounced me, and I barely beat Rob before excusing myself and my sickness to some well-earned sleep.

CHENGDE TO BEIJING

APRIL 27

It was raining, and aside from our enterprising "guides," we had the Great Wall to ourselves.

The "guides" are part postcard sellers, part water vendors, and part helpers. They each adopt a tourist, and help them over the rough

patches of the nine kilometer Great Wall hike from Chengde to Simitai. In return, the unspoken agreement is that the tourist will buy something from the helper.

I was really ill by this time, and the hike to the Great Wall and back to the waiting minibus was enough for me. I watched the group hike away into the mist, and had a look around.

The Great Wall was long -- 6000 kilometers long. It disappeared into mountains on either side of me. It followed the mountain ridges,

steeply going up and down. But it wasn't very wide, and clearly the claims that astronauts could "see the Great Wall from space" were absurd. As one guidebook, "Central Asia Overland," had put it, "parts of the Great Wall are so rundown that you can barely see it from the Great Wall itself."

Still, it was awesome. Although as a concept, the Great Wall was flawed. When has a mere wall, even a really long fortified one, kept

out anybody? Walls require sentries and weapons.

The Great Wall, I reflected, was built to keep foreigners out. Now, it drew them in by the busload.

A prime example of this pulled up as I sat in the minibus, waiting to drive to meet the group. A bus full of forty French tourists pulled up. The locals formed a line of scrimmage, a human barrier that left only a single opening for the tourists to file through. One local would break off for each tourist that crossed through, and the game would begin.

line of scrimmage

line of scrimmage

The group rejoined me after their hike, and we drove back to Beijing, where the hotel staff cheerfully handed me my FedEx. It was a variety

pack of freeze-dried gourmet foods for me to eat on the Trans-Siberian, and my favorite t-shirt.

Michael and Yancey, fearless consumers of all foods local and world-class championship bug-eaters, had been downed by the mundane. Michael

had been felled by a rotten pineapple he should have had the sense not to eat, and Yancey had gotten the same miserable cold that had knocked me out. Rob had eaten with Michael, and was sick too.

We made a pathetic foursome, and decided to eat at McDonald's in order to get something "bland and starchy" into our uncooperative systems.

This was an ideal opportunity for me to continue my research into local McDonald's dessert pies. I'd had "pineapple pie" and "corn pie" in Bangkok, and the Chinese McDonald's menu featured "red bean pie."

Rob placed the order.

"Apple?" asked the doubtful cashier.

"No, red bean," said Rob.

"Pineapple?"

"No, red bean." Rob pointed at the pink packaging around the red bean pie.

The cashier brought over a pineapple pie and a red bean pie. She shoved the pineapple pie forward.

"Pineapple?" she said.

"No, RED BEAN!" Rob grabbed the red bean pie from her hand. We split it four ways. It wasn't bad, but I had to admit that the pineapple, and even the corn pie, tasted better.

Most of our Intrepid group

Most of our Intrepid group

BEIJING TO MONGOLIA

APRIL 28

Michael walked us to the railway station in the morning. We stopped by Starbucks for takeaway muffins, and I stuffed then into a clean

sanitary napkin bag I'd swiped from the hotel expressly for the purpose of storing food.

Yancey and I were well supplied with snacks for the overnight trip to Ulaan Bataar, and we'd made a last minute run to the pharmacy to stock

up on tissues and codeine cough syrup. We loaded into our two-person compartment, said our touching goodbyes, and left the station for the unknown weather ahead. We coughed and gasped our way out of the Beijing station.

NEXT: Lots of coughing! A nice old Mongolian man calls Yancey a

horrible name! A night in a freezing-cold ger!