Mayonnaise, Mutton, and Mongolia

BEIJING TO MONGOLIA

APRIL 28

Yancey and I, with our sniffling and coughing, made a miserable pair. Months ago, I'd booked us a two-berth compartment out of fear of the unknown, not knowing we'd need it to quarantine ourselves away from the other passengers.

Our train pulled out of Beijing early on Saturday morning. We closed and locked our door, opening it only to run to the toilet.

The Mongolian train toilets were western-style, featuring pedal-controlled flaps that opened the bowls onto the tracks below, while

squirting out accompanying water. Technologically, they were superior to the no-water/no-flap Chinese train toilets, but I actually preferred squat toilets on trains, as the toilet seats were invariably disgusting due to the physics of motion, and bad aim.

The floors were soaked too, reminding me of Yancey's words of wisdom to Michael: "always double-knot your shoelaces." I developed a system of using the toilet in the next carriage, so that my shoes were dry by the time I reached our own compartment.

sick Yancey snoozes his way to Mongolia

sick Yancey snoozes his way to Mongolia

We slept, ate, and hacked our way through the day. As our train approached the border and the Gobi Desert, a fierce sandstorm started

up. Our window was sealed, and our compartment door shut tight, but dust found its way through the cracks. Soon we were breathing through our shirts. Every exposed surface, including our luggage and fleeces, was covered in thick dust.

The storm had just begun to dissipate at nine when the train halted. A uniformed Chinese woman rapped on our door and barged in, demanding our passports. She looked under both berths, but gave special attention to Yancey's possessions. She paged through his (empty) sketchbook and book of Mao sayings. She spent extra time staring suspiciously at his copy of Edith Hamilton's "Mythology." I found this hilarious but dared not laugh. She left, and we drifted off to sleep in our layers of dirt.

And then we were interrupted again. Every time we thought we'd sleep, an official came in with a new form to fill out.

China and Russia operate on different rail gauges, so the "bogies" are changed at the border. This takes hours while the train jumps and

starts. The Customs officials had ample opportunity to wake us up repeatedly.

By the time an efficient Mongolian official welcomed us to her country, it was one in the morning. Bleary-eyed, we thanked her. As I went to sleep, I recalled the six-hour taxi ride from hell that Yancey and I had lived through together in Jordan. After that, he'd sworn never to travel overland with me again.

"I'll go with you, but you can go overland. I'll fly in," he'd said. True to his word, the next time we'd traveled together, he'd flown to Belize while I'd endured a 20-hour bus trip from central Guatemala.

I hoped that Yancey wasn't pretending to sleep while secretly recalling his oath.

ULAAN BATAAR, MONGOLIA

APRIL 29

I awoke in the most remote place I'd been in my life.

Mongolia, barely visible through the dust-covered train window, looked exactly like I'd imagined it would look. Yellow-brown hilly grasslands stretched for miles in all directions, dotted with the occasional round, white nomad tent, or "ger."

Well-dressed cows -- it's cold in Mongolia -- and mangy dogs made up the majority of the wildlife. Yancey had read that dog lickings can

carry rabies, and he kept threatening me with this.

"Hey, Yancey," I said. "Mongolia looks like Wyoming."

"That dog wants to lick you," was his reply.

Our train pulled into Ulaan Bataar.

"It's snowing," said Yancey, distracted from his dog-licking information.

I looked outside. Sure enough, powdery white snow was falling from the sky. And even worse -- it was cold.

A 30-ish Mongolian man in a sportscoat stood on the platform, holding a flimsy piece of notebook paper that read "Javins/Labat." He was Altai from Mongolia Outback Tours and was here to take us to our homestay. He took us to the moneychangers first, where I was able to trade in my Chinese yuan for Mongolian currency and a few Russian rubles. He then dropped us at an aging apartment complex on the edge of town.

Welcome to Mongolia!

Welcome to Mongolia!

Mrs. G and Mr. A ushered us into their fourth-story walk-up flat. It was small, simple, and comfortable, but was large enough for Yancey and

I to have separate rooms.

Mr. A retired to a closed-door TV-watching room, while Mrs G fed us tea, bread, and jam. She spoke little English, but was fluent in Russian and Mongolian.

"What country?" she asked.

"U.S.A." I replied.

"Stadt?"

"New York," I said unthinking. And then I realized she'd asked me a question in German.

"Sprechen Sie Deutsch?" I asked her.

"Ja! Und Sie?"

"Bisschen," I said. "A little."

Mrs. G had learned German in Russia. Mongolia had been an independent state, but had been under the watchful eye of the Soviet Union until

its collapse. I'd previously considered my five years of high school German lessons to be a total waste as I barely remembered anything, but this was clearly not the case. Yancey was as surprised as I was to hear me speaking German with this Mongolian grandmother.

In broken German, Mrs. G offered to cook us a traditional Mongolian meal. We agreed -- certainly we had no pressing engagements. She got to

work while we bundled up in fake North Face and walked to the Ulaan Bataar center.

The paved boulevards of UB were filled with buses and small cars, but no motorbikes. Cars obeyed speed limits and traffic signals, and there

were no honking horns. Short, dirty, cement buildings lined the streets, but we couldn't stare for more than a second without being blinded by snow.

The older people we passed were dressed like Jedi Knights in earth-colored, knee-length flowing robes, bound at the waste by sashes. The

kids, meanwhile, dressed in the contemporary uniform of the urban hipster -- baggy pants, messenger bags, Fuju shirts. Some were even attached to miserable-looking rottweilers, shivering on their leashes.

"Where do they learn about style?" wondered Yancey.

We hurried back to Mrs. G's. I'd claimed vegetarianism after reading about a Wanderlust" magazine article about Mongolian meals that featured sheep's stomachs and eyeballs. Mrs. G had made Yancey some mutton dumplings but had put tofu, cellophane noodles, and cabbage in mine. I have a bad allergy to soy but ate the dumplings with loud, lip-smacking "yums" of appreciation.

We were also served Mongolian tea, which is more milk than tea. With my dairy sensitivity, that would've knocked me down for a day, so Yancey switched cups with me after drinking his own. As the woman, it was customary for me to refill the man's teacup, and Mrs. G pointed this out to me every time she'd come in the room and notice Yancey's tea getting low. I'd nod and Yancey would snicker, but as soon as she left, he'd carefully pour his own tea.

I showered the dust of the Gobi off, and my mouth swelled up from the tofu. That was new -- usually I broke out in hives on my arms and legs. I found Yancey watching MTV in the den a/k/a my room.

"I know where they're getting these hip-hop fashions from," he said, pointing at the TV.

The variety of TV was astonishing, after weeks in information-starved China. We switched through Russian programs, Chinese shows, India

videos, BBC World, and "The Phantom Menace." And earlier I'd logged onto both CNN.com and MariesWorldTour.com with no problems. As much as I'd enjoyed China, it was a relief to leave the censorship behind.

APRIL 30

The snow had disappeared and I awoke to a bright, sunny day. Mrs. G stuffed us full of blueberry pancakes before going off to work at the

university.

Mr. Altai dropped by on his way to work, and briskly walked us the four kilometers to the Mongolian Outback Tours office. Somehow, Yancey's

itinerary didn't include his going to stay in a family ger in the countryside. The error had been made a long time ago, and there were a dozen times when I should've caught it. But I was only dealing with my trip a leg at a time and hadn't even looked at his vouchers until we'd met up in China. He, in turn, expected that I had our itinerary under control.

We met with Mr. Bata, Altai's boss. He made the changes swiftly. Tomorrow, we'd leave UB, drive in the morning to the ger, spend the

whole day and night with the family, and then drive Yancey to the UB airport in time for his morning flight to Beijing.

"Mr. Bata," I said through my phlegm, "Yancey is only transiting through Beijing. He's just getting off one international fight and

boarding another, to the States. Does he need a Chinese visa?"

"No, no," said Mr. Bata. "As long as he stays in the transit lounge, he does not need a visa."

We thanked Mr. Bata and spent the day aimlessly wandering around UB. The easygoing traffic, friendly people, and clean air charmed us, but

we were both still coughing. We tired early. We stopped by Mrs. G's once, and her husband showed Yancey his rock collection.

We visited the Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts, with its fantastic paintings and tapestries of Hindu and Tibetan deities. The most famous

painting in the collection is called "A Day in the Life of Mongolia." Its giant canvas features instances of Mongolian country and city living, including naked people in gers and dogs in heat. It has spawned a slew of lewd imitations that are available in all Mongolian souvenir shops, and on the fourth floor of the State Department Store.

We went home early and were both in our pajamas, ready to go to sleep, when Mrs. G and Mr. A barged into my room, carrying a bottle of vodka

and four glasses.

"Oh my god, I'm going to die," I thought.

I had a tiny sip of vodka and feigned a coughing attack (it wasn't hard). Yancey drank his own, and then took my glass and downed it

before the couple could protest.

Mr. A liked this. He loved Yancey, his new friend who liked rocks and vodka. He poured Yancey a third, then a fourth glass.

"What is your Arbeit (work)?" asked Mrs. G.

I showed them my Spider-Man business card and found the word "artist" in the phrasebook. I didn't think they'd understood but then Mr. A left the room and returned carrying a child's "Batman" Halloween mask.

They brought out their guestbook, full of thanks in many languages. Yancey drew a "Superman' figure and I colored it. Mrs. G told us that

her daughter works at the Mongolian Embassy in Washington DC, and I managed to convey that both of our mothers lived near there.

Then they asked us the questions they'd been dying to have answered for two days.

Yancey and I are both mutts in the truest melting-pot proto-American sort of way. We both look pseudo-ethnic, but no one is ever quite sure

of our heritages. In places where there are relatively few mutts, such as China and Mongolia, people are curious.

"You nee-ger?" Mr. A asked Yancey. I was stunned into silence but Yancey didn't miss a beat. Later, he explained to me that he wasn't

surprised because the only exposure Mongolians had to African-Americans was through MTV, "Pulp Fiction," and various modern Hollywood movies.

"Um, no," said Yancey, pointing to an atlas. "Louisiana." He made little hand motions pointing to Mississippi and Africa. "Mother,

Father, Mississippi, then Maryland and New Orleans. And Senegal. Long time ago, Martinique."

This satisfied the couple. They surely didn't understand what Yancey had said, but clearly his family came from all over.

They turned to me.

"You, Anglo-Saxon?"

Responding was difficult, as I don't really know my heritage. There's a lot of mixed European on one side, and pure hillbilly mixed with Native American on the other.

our Mongolian grandparents

our Mongolian grandparents

Native Americans never tapped their lips with their palms and said "woo woo woo." But in this situation, there was little else I could do to communicate. I braided my hair and said "woo woo woo." The Mongolians laughed with delight. They got it instantly.

The homestay was a charming, rewarding experience. It was also a pain to have the couple constantly doting on us. When I returned to UB after the night in the ger, I thought, I'd stay in a hotel.

MONGOLIAN COUNTRYSIDE

MAY 1

Altai and a driver picked us up early and drove us off, past the rundown ger suburbs of UB, into the stark Mongolian countryside. Our

driver's Japanese SUV was right-hand drive, while most of the cars in Mongolia were left-hand drive. Mongolians drive on the right, and a law had recently been passed forbidding the import of right-hand drive vehicles.

Oroo

Oroo

We stopped at a particularly cold, high, desolate point to walk clockwise circles around a pyramid-shaped oroo, or Shamanist pile of

rocks. The surrounding craggy peaks were covered in snow. I could see my breath, but could see nothing out of my peripheral vision as I was bundled up and hooded.

On we went to our ger. The "family" turned out to be a middle-aged farmer couple whose children had flown the nest for the big city.

our ger

our ger

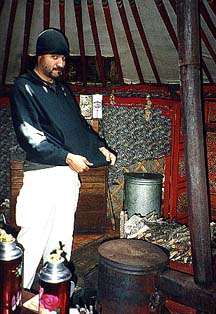

The couple vacated the ger, moving into a nearby small, concrete building for the night, along with Altai. Yancey and I were left alone

with the woodstove in the ger.

"I kinda thought we'd be staying with the family," groused one of us, but it was what we both were thinking.

I made the first trip to the outhouse, which was fairly painless because the cold kept the stench at bay. It was a three-walled wooden shack with two holes cut in the floor, over pits. The fourth side faced the mountains, and was open.

"What would you like to do?" asked Altai, when I returned.

"Um, well, what can we do?"

"You can eat lunch, and you can ride horses."

"Okay."

The farmer man went off to find the horses. Yancey and I huddled around the woodstove, freezing and trying to decide if this experience was cool and exotic, or just miserable.

"I love this. It's like a wigwam. This is ger-reat!" said Yancey. And then lunch arrived.

Yancey and Altai had grisly, chewy, vague mutton. I was the lucky recipient of a ball of rice held together with mayonnaise and topped with daubs of ketchup. I tried to pawn it off on Yancey, but even he, eater of bugs, had limits. As soon as the cook left the ger, Yancey and I started feeding our food to the fire.

We grilled Altai about life in Mongolia.

"How has Mongolia changed since the fall of the Soviet Union?" I asked.

"It is more free, but the economy is not so good," said Altai. It was the same story the Russian sailors had given me about their lives in St. Petersburg.

"The young people are happy, and see opportunity. The old people miss the past."

He also pointed out that Mongolia had never been part of the Soviet Union -- it had been controlled by the Soviet Union, like Czechoslovakia. And he told us about three hundred Mongolian students that were studying in San Francisco, and had recently gone see visiting Mongolian heavy metal band "Hurd" (pronounced "Horde").

Shortly after, we went for a walk -- straight to the nearby tourist ger camp, where I ate carrot soup and washed my hands in hot, running water.

Marie visits the tourist gers

Marie visits the tourist gers

We walked back to our ger, gingerly avoiding cow dung and the occasional cow carcass as we walked across the frozen ground.

A furry puppy followed us. Yancey, at great personal risk of rabid lickings, scratched its belly. The schizophrenic weather changed again,

and it started to hail, so we ran back to the ger. The farmer and the horses were still missing.

We took shelter from the hail in our ger, and huddled by the fire.

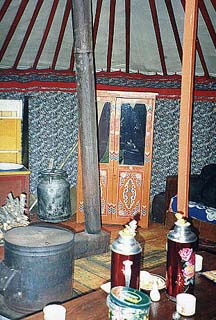

Our ger consisted of five semi-white canvas walls, held together in a near-cylinder. Besides the woodstove in the center, there were two

cots, a refrigerator, and a washbasin lining the sides. A small table in the center held some stale breadsticks that we were surreptitously using as fuel. A dried bear paw in the corner had no significance, except as a show-and-tell piece.

the steppe is littered with cow carcasses

the steppe is littered with cow carcasses

The hail stopped, but it was too cold to go outside and we had nowhere to go. The farmer never returned with the horses. Yancey had gone from thinking it was "ger-reat" to agreeing with me that this was cold and miserable. He was looking forward to getting on the homeward plane in the morning.

Yancey and I were finishing our trip together in the same way we'd started it; waiting on something that never came. In Shanghai, we'd spent an afternoon waiting for a bus. In our ger, we waited on horses.

Altai was getting frustrated with the missing farmer and absent horses. He felt responsible and finally took action. He rented horses from the neighbors.

There were only two horses, so we had to go without Altai.

"Can you ride?" he asked, worried.

"Sure, no problem. Yancey's dad even owns a horse farm," I said with confidence.

"It's okay anyway," said Altai. "These are very gentle horses."

Yancey and I got on the horses and rode across the rode, out of earshot of Altai. Yancey's horse immediately disobeyed him and stuck its head in the creek to drink. It refused to go further.

"Kick it, Yancey," I said.

"Y'know, my dad has a horse farm, but that doesn't mean I've been on a horse," said Yancey. "My dad won't let me near his horses. They're too valuable."

"You've never been on a horse?" I said, dumbfounded but also delighted with my earlier exaggeration.

"I've been on a donkey and a camel. It can't be that different."

Kick it, Yancey!

Kick it, Yancey!

I almost fell off my own horse laughing. Yancey, meanwhile, was encouraging his horse to move by telling it to "go, horsie." He was

hopeless. Finally, his horse decided to move and we slowly trotted up the hillside.

The weather had turned sunny and the vistas were spectacular, but soon we had to return to the ger for our dinner.

I had brought my own; grainy couscous, just add water. Yancey and Altai had fried meat pies, that they both claimed were tasty. The guys talked sports, and we learned that Mongolia has had to quit funding Olympics-training, due to budgetary constraints.

ger rhymes with brr

ger rhymes with brr

Finally, it was dark, and time for sleep. The farmer had finally appeared, still mysteriously horseless. He dumped coal into our

woodstove. Yancey and I covered covered up in North Face sleeping bags -- two each -- and went to sleep.

Or I did, anyway. I am good at sleeping. Yancey was kept up all night by barking dogs and his own shivering.

ULAAN BATAAR

MAY 2

At six, we raced to the outhouse and then into the car. We couldn't wait to leave the freezing ger behind us. The farmers came along. They

were going to UB to visit their children.

how could we leave all this?

how could we leave all this?

The spectacular snow-covered peaks were some comfort; the views really were incredible. And they were much nicer to see from inside a heated

SUV than from the dung-covered front yard of a working ger.

We dropped Yancey off at the airport. I loaded him down with stuff to take home for me and got back into the car. I'd be solo again,

circumnavigating the world alone by surface transport. I was sad -- it had been fun to have company, but I was also excited to be "on the road again," so to speak.

Finding a hotel took some doing. We went to a guesthouse, "Nassan," that was only four dollars a night. But it was a crowded room full of

young travelers sprawled out just a few feet apart. Altai took me to a few overpriced hotels, and finally the driver had an idea. We checked out Hotel Ekhlel. It was warm, friendly, clean, and safe. My en suite bathroom had a strong supply of hot water, and I even had cable TV, all for $20 a night.

After the night in the ger, I was thrilled to have a hot shower. Mr. Bata called while I was washing. Never mind, I thought, I'd call him

back after I'd found some coffee. I was alone in Mongolia, what could possibly be urgent?

NEXT: Yancey is stranded in Ulaan Bataar! Cuban Americans make French toast in Mongolia! Petty criminals strike! And we buy a Hurd cassette!