Loop To Lalibela

(Marie-mail #61)

AXUM, ETHIOPIA

NOVEMBER 11

We had lined up a taxi the night before, and at 5:30 a.m., Monica and I left the dark, silent "Axum Touring Hotel." The members of our Dragoman overland group were all sleeping off the effects of last night's optional excursion to the Ethiopian disco. My group experience petered out without drama.

by bus to Mekele

by bus to Mekele

All buses in Ethiopia are scheduled to leave at six in the morning, and are forbidden to drive after dark. Dark always falls around 6:30 p.m., so buses leave as early as they can to take advantage of the daylight.

In reality, the buses, like all African buses, leave when full. But in Ethiopia, this is no problem, as buses fill up quickly.

A crowd milled around the gate outside the bus lot. At six on the dot, the gates opened and the crowd poured in to excitedly angle for seats.

Monica and I followed uncertainly. We hadn't worked out the system yet.

Fortunately, an Ethiopian man took pity on us. He was standing with a suitcase and was there to see his brother off.

"I will take care of you," he said. "Trust me."

We were happy to. The chaos of the bus terminal made no sense to us. Only later did we work out that we had to mercilessly shove our way on the bus, as it filled up quickly and then we would have had no choice but to wait for the next day's scheduled departure.

The bus doors opened. I had to get my pack on the roof, so Monica was on her own, trying to get through the bus doors along with fifty experienced Ethiopians.

She pushed and shoved and tried to get on.

"Faranji, faranji, run run!!" shouted a gleeful old man. He was hooting with laughter at the foreigner trying to elbow out the Ethiopians.

Monica might have succeeded or might have failed, but our new friend was having none of it.

"Come here," he said, motioning to the seat next to him. He'd miraculously floated through the mob, gotten the second seat from the front, and was saving it for us. He left us with great thanks for allowing him to practice his English. We assured him the pleasure was ours.

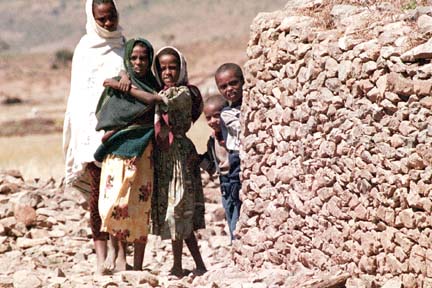

country kid

country kid

People were standing in the aisles, and more were trying to get on. The conductor began the long process of evicting standing would-be passengers, one by one. Each one screamed bloody murder, and while I could not understand the proceedings, I suspected each passenger had a sob story of why he should be allowed to board. The conductor, old hand at party pooping, ejected them all.

Monica and I watched the proceedings with astonishment. The curtains on the little bus were drawn and we roared out of the bus park.

No sooner were we around the corner and out of sight of any bus officials, than the bus pulled over. The passengers who had been thrown off all reboarded the bus and we drove out of the ancient city of Axum, en route to the Tigrean metropolis of Mekele.

The Xena: Warrior Princess battle cry (or at least the Ethiopian version of it) came on as Ethiopian pop blared from the overhead speakers, and the bus horn (used with gusto whenever a goat or vehicle approached) sounded a musical song when pushed.

The pop music switched off and morning news came on. To us, ignorant of Amharic and more so of the northern Ethiopian language of Tigre, it sounded like "blahblahblah America blahblah Taliban blah blah Afghanistan."

"Top scenery," I joked with Monica. We were climbing a winding paved road that took us up a mountain.

"V. scenic drive," she replied. Our Dragoman leader Mark had used these terms in his itinerary descriptions.

"V. scenic drive"

"V. scenic drive"

A siphon hose was on the luggage rack above two Spaniards in front of us, and they flinched when gasoline started to drip. The two men's heads were getting dirty, but they had wisely covered their packs - now on the roof -- in plastic raincovers. I'd regret not doing the same - my pack was covered in red dust when I took it off the roof.

The sun came out, unrelenting as always, and the Ethiopians who were not covered by the curtains opened their umbrellas.

"That's the first time I've seen anyone open an umbrella on the bus," observed Monica. I didn't answer. I was engaged with an unsuccessful attempt to surreptitiously capture the Kodak moment.

Our slow spiral up the mountainside groaned to an unexpected jerky halt when a rock lodged itself between two of the back tires. Everyone piled off the bus to pee or gaze at the green mountains nearby. One man introduced himself in halting English and showed his I.D. He was from the Mekele tourist office, but could only provide names of expensive hotels to us so we declined his assistance.

removing a rock from the tires

removing a rock from the tires

The bus stopped other times, to let people embark or disembark in small towns, and once we had to reclaim a sack that flew off the roof. Monica and I were thrilled to be on Ethiopian public transport. We were talking to locals, watching the scenery and enjoying the independence of not being safely ensconced in the tourist bubble.

At the town of Adi Grat, everyone had to change buses and the new driver saved us the front seat. A kid came on to sell individual sticks of gum, but I declined in favor of my packed lunch of pb&j.

Our long bus ride left us in Mekele, the thriving, upscale capital of Tigre province. The current Ethiopian president is from Tigre, and he has poured funds into the region. To Monica and I, Mekele was just an overnight stop halfway between Axum and Woldia, the gateway to Lalibela. We had no expectations of it, unless you count expecting the usual dusty, small Ethiopian town.

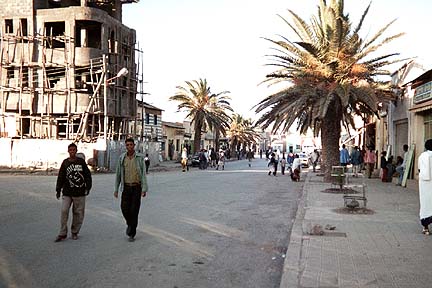

Mekele

Mekele

Instead it was an oasis of coffee shops, trendy fashion boutiques, juice bars, and stationery stores. We caught a horse-drawn taxi to Havelti Hotel, checked into two single rooms, and walked to the center of the hip downtown.

We had a juice at a juice bar. It was so good we both ordered seconds. The waitress cheerfully mimed and improvised to communicate with us. Others smiled and left us alone. Mekele was a great place.

An office supply store featured internet access, and while I checked my e-mail, Monica conversed with the storeowner.

"Do you know the difference between faranjis and Ethiopians?" asked the owner. Faranji is the Ethiopian word for foreigner.

"Mmm... no. What?"

"When faranjis go out for coffee, they all pay separately."

There was no arguing with that. We also discovered that faranji describes foreigners of European descent. Asians are not considered faranji, and that Tigre province injera bread differed from southern Ethiopia injera.

After pizza amongst middle-class Ethiopians, we walked back to the hotel. We got lost, and inquired as to the way. A local man altered his course and escorted us all the way back. I wondered is Mekele really was an oasis of friendliness and politeness, or if the difference was that Monica and I were traveling alone instead of in a group. We were able to deal with people one on one instead of en mass, and everyone seemed happy to share their lives with us.

MEKELE TO WOLDIA

NOVEMBER 12

This time we knew the system. We were exempt from waiting, and blustered through the bus park gates before they opened. No one complained. Faranjis were, not unjustly, considered incapable of fending for themselves against the packs boarding the buses.

We were safely seated on the Woldia bus by the time the floodgates opened to let passengers sprint for their buses. I speculated that all the runners we'd seen training in Addis Ababa were not just jogging for health reasons, but to be in shape for the Great Bus Race.

The passengers were joined by the usual assortment of vendors, beggars, and priests wanting alms. One man with no legs hopped using his hands, which he protected with wooden blocks. "The hands equivalent of crutches," I realized. They seemed more durable and stable than the others I'd seen wearing flip-flops on their hands.

A plastic jug flew off the top and the bus screeched to a halt. As usual, the conductor blithely leapt out of the bus, tossed the jug back on top and got back in.

Everyone giggled. The jug had landed in cow poo, and now the conductor had it on his coat. Disgusted, he removed the coat and wiped it on the grass, going coatless for the rest of the ride.

The obligatory bus breakdown occurred before lunch, and antifreeze drenched the road under us. The road, so nice and paved before, had become dusty and bumpy after our lunch stop in the town of Maychew. A new road was being built by a Chinese company. The first time I spotted one of the workers out of the bus window, we both stared at each other in astonishment. The Chinese man's face broke into a big smile and he waved as we drove by.

Our breakdown recurred several times, and the charm of independent travel had worn off by the time our bus crawled into Woldia at dusk. A kid named Lyuwork said he knew a man who was driving a Land Cruiser to Lalibela in the morning. We tracked him down at a bar and negotiated our passage.

The driver agreed to take us to Lalibela for 100 birr each. With a Cruiser, we'd get there in three or four hours. The bus would have taken eight. I needed to get to Lalibela in the morning, to see the sights in the afternoon. Lalibela is, according to Philip Briggs in his Guidebook to Ethiopia, "arguably the one place in Ethiopia that no tourist should miss." I had to be on the bus back to Gonder on the morning of the 13th. If I missed that bus, my whole schedule north would be thrown off and I'd be endangering my once-weekly train/ferry connection out of Sudan, and thus would miss my cargo ship home. My ship, once scheduled to pick me up in Alexandria, Egypt, had changed its itinerary and I'd be cutting it dangerously close to get to its new stop in Ashdod, Israel. I was glad to have found the Land Cruiser, as it made my tight schedule work.

"This is where I am," I thought, testing out Karen Blixen's phrase about Africa, "this is where I ought to be." But I was tired of Ethiopia and it didn't ring true. Besides, my mother was expecting me home for Christmas. I needed to get a move on.

WOLDIA TO LALIBELA

NOVEMBER 13

Lyuwork met us in the pastry shop at 8:30 in the morning, as we'd agreed. A young church deacon was there too, having bought the fourth seat in the Land Cruiser. Unfortunately, the driver was nowhere to be found.

"He will be here," said Lyuwork. "I promise."

The man finally drove by - in a pickup, not a Land Cruiser - and explained that he would be leaving late, but that he would be leaving.

By 10:30, we'd given up and were trying to hitchhike out of Woldia. The bus had left promptly at six. My hopes of seeing the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela were evaporating as the schedule tightened.

Lyuwork and Monica

Lyuwork and Monica

We left our bags sitting on a bench in a small soda shop, and Monica and I took turns hitching outside the gate. I was on bag-guarding duty, and put moisturizer on my hands. The proprietress looked curious, so I gave her some and showed her how to rub it in. She was delighted, and I could see her demonstrating the rubbing motion to her friends later.

Monica was having no luck, and succeeded only in determining that we should have taken the bus. I had no luck either - a green truck passed me en route to Lalibela but wouldn't stop for us, because it wasn't considered proper for faranji to sit in the back of a truck.

"We'll sit anywhere! We just want to go to Lalibela," I said. It seemed hopeless.

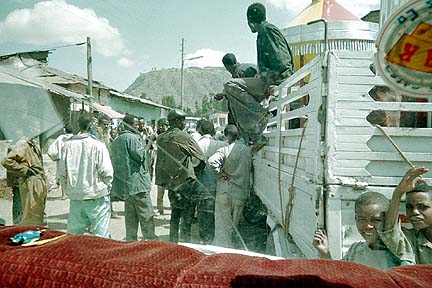

hitching a ride

hitching a ride

Finally, an Isuzu truck stopped across the street at the Mobil station. They were, they said, going to Lalibela at 2 p.m. If we hadn't found a lift by then, they would take us.

We continued to try to hitch for a while, and finally sought cover in the shade. Monica and I sat depressed, wondering if the Land Cruiser guy had gone after all, and perhaps found other riders. At lunchtime, we decided to go back to the Lal Hotel, to get some food before our 2 p.m. ride showed up. I'd go in one horse-drawn buggy with my pack, and Monica and Lyuwork would follow in a second.

The cart driver was saying something cheerful and unintelligible to me in Tigre or Amharic, and I was nodding politely when an Isuzu truck roared by with Monica and Lyuwork in it. They honked at me and waved frantically. The Isuzu was leaving early.

"Stop!" I said to the cart driver.

He smiled happily at my excitement and continuing taking me towards Lal Hotel.

"No, no, STOP!" I pretended I was leaping off the cart. He shook his head, but continued. I reached over, grabbed the reins, and tugged. We stopped. I leapt off with my pack, threw two birr at him and chased the Isuzu. Several hands reached off the Isuzu bed to pull my pack up. I ran around to the passenger door and boarded. Monica waited within. We were both excited. We were going to Lalibela after all!

But first, there were a few stops to make.

We drove down some back streets, into the depths of Woldia. The driver parked behind another Isuzu. We were going in a convoy. He charged us 100 birr each, and we agreed to 100 now and 100 later. They wanted all the cash up front, and made a big deal out of our refusal. Finally, Lyuwork agreed to be responsible for the second hundred should Monica and I refuse to pay upon delivery.

We sat for hours, waiting for the convoy to leave while cargo was loaded onto the back. People stood and stared unabashedly at us faranji. I bought some ancient, dry cookies for our lunch. I took to amusing small children with twisty finger games, which was fun until they got demanding.

curious onlookers stare at faranji in Isuzu

curious onlookers stare at faranji in Isuzu

Finally, after three, the loading was complete. If I understood correctly, we were carrying 100 tons in a 50-ton-max truck. The driver hopped in and we started up.

"Lalibela!" I said, relieved to finally be moving.

Ten minutes later, we were back at the Mobil station, getting gas and washing windows. The driver moved the truck to the side of the Mobil station and disappeared into the hotel across the street for a spot of tea. We waited until five. Monica and I were frantic by now, and decided to take action.

"I'll talk to this guy who works on the truck, and you go talk to the driver," said Monica.

I went into the hotel and found the driver.

"Please," I said in Amharic, pointing to the corresponding word in the phrasebook. "Lalibela." He motioned to me to sit down and made reassuring clucking noises. I refused and went back outside, reiterating "please" for good measure.

Outside, Monica made more progress. The guy who worked on the truck turned out to be Mendes, the truck guard. His English was fairly good. He told Monica we were leaving at sundown. The truck was too overloaded. We could only travel after dark, because otherwise the police might see us.

"Overnight," said Mendes. I thought this was a reference to when we were leaving. Of course it turned out to refer to the duration of our journey in the slow, overloaded truck.

Monica and I discussed our situation. What could we do? I was pushing it badly on the schedule and had counted on the short ride in the Land Cruiser. We were still a long way from Lalibela and I was going to have to miss Lalibela if I wanted to be on that cargo ship out of Israel on November 25.

"We could go on the morning bus," said Monica. But I said no, because that meant I would not be able to get to Gonder on schedule. I had to work out a Plan B.

"My only chance," I said, "is to get to Lalibela tonight, see everything early in the morning, and pay a fortune for private transport to Gonder, to arrive tomorrow night. It will be a long day, but it's the only way."

Monica agreed. We waited, but our spirits fell with darkness.

At seven, we finally pulled out. The driver had brought along a bag of leafy green qat, a popular chewable stimulant. But at least, I thought, he hadn't opened it yet. He was still "sober."

A new passenger had gotten up front with us, so now we were four. The Ethiopians argued with him to get out and quit crowding the faranji. He refused. The other passengers - 20 to 30 of them - climbed into the truck bed to perch haphazardly on the cargo.

"Lalibela!" I declared with all the enthusiasm I could muster.

"Lalibela!" confirmed the driver.

"Name?" he asked.

"Marie."

"Monica."

"Ah, Monica Lewinsky." This always happened when Monica introduced herself in Ethiopia.

"City?"

"New York," I said. Monica was from Scotland.

"Ah, Osama bin Laden," said the driver. I nodded. I was used to this response too.

We got a few kilometers out of town and stopped in the darkness.

"Mendes," yelled the driver. The truck guard appeared at the window. He was one of the people perched on the cargo.

Together, the driver and guard opened up the engine compartment and took out what looked like some sort of spark plug. They used fuel to clean it and replaced it. Beams of light cut through the darkness from the back. Every passenger save the babies seemed to be sporting a flashlight. Occasionally, one would flash past a face and we'd get a glimpse of a cheerful Ethiopian smiling at us.

On we went up, the overloaded Isuzu struggling up Ethiopia's steep mountains. The light from the truck behind us threw our shadow - a giant truck profile dotted with heads and bodies on top of cargo - onto the cliff face.

"My Eye-suzu - fantastic," declared the driver. Isuzu is pronounced "Eye-suzu" in Ethiopia. Monica and I politely agreed that it was fantastic.

The fourth cab passenger opened the bag of qat. Monica and I watched nervously as the driver and passenger started chewing. I tried not to think about it.

"You like Kenny Rogers?" the driver asked, before pulling out a Michael Bolton tape. Thankfully, the cassette deck was broken.

Monica dozed off a few times, waking the second we drove into potholes. I was unable to sleep. Finally, after midnight, we turned onto a dreadful dirt track the driver called the "Lalibela Road."

Both he and the passenger were getting fresh by now, and were nuzzling closer to us in the already tight cab. I spotted Monica firmly move the driver's hand from her knee. The passenger leaned into me suggestively.

According to the Lonely Planet guide, Ethiopian women often play hard to get even when interested in a man, so a polite "no" doesn't really do the trick. We were both aware of this and swapped places to confuse our suitors. I now sat next to the driver and Monica was between the other passenger and me. The men laughed and didn't hassle us again.

I tried to sleep, but my left buttock was squashed into a plastic tray table and a Coke bottle, while my right was squeezed up against Monica, who had herself been mistaken for a fluffy pillow by the passenger. I was afraid to sleep anyway. If our qat-chewing driver started to nod off, I wanted to be ready to prod him.

The ride was interminable and it got cold in the cab. The passenger window was permanently cracked open and rolled neither up nor down. The door handle was missing in addition to the window handle. A coat hanger got us in and out.

Finally, I saw mirage-like lights in the distance.

"Lalibela airport," declared the wide-awake driver. This woke up Monica, who was also pleased to be near the journey's end.

As we stared ahead at the airport, our headlights cut off. All indicator lights, parking lights, and electrics just vanished.

This had happened to a bus I'd been on in Uganda. The bus driver had sensibly applied the brakes.

My luck had run out. Our driver panicked. He jerked the wheel left while hitting the brakes. The left side of the fantastic Eye-suzu clearly, in seeming slow motion, crested over the shoulder.

I remembered Mark's lecture on the Dragoman Mercedes "point of departure" and made a mental note to tell him the point of departure for an overloaded Isuzu truck is about twelve degrees.

We flipped, landing at a 45-degree angle, squarely on the driver's side. The driver and passenger were silent, stunned in the darkness. From the smell, it was apparent that the driver had shit his pants. The windshield had spidery cracks across it and a startled wailing had erupted outside.

I broke the silence in the cab.

"I'm okay," I said clearly.

"I'm okay," said Monica.

"Let's get my bag and get out of here. We'll walk."

"Right." Monica agreed. We'd had enough madness for one day.

The other passenger, from where he lay beside the only accessible door, made no movement.

"OPEN THE DOOR," I ordered him with all the firmness I could muster.

"I can't," replied Monica, who assumed I'd been talking to her. The passenger blocked her access to the coat hanger handle. For a minute, I thought we were trapped as I realized the only working door handle and window was now parallel to the ground.

Monica poked the passenger and made him help her. Together they managed to lift open the door, which had become very heavy in its new incarnation as a hatch.

The passenger climbed out and turned to help Monica out. But the driver suddenly came to life and clambered over Monica and I in a rush to escape. We let him go first. He was obviously panicked. He disappeared off into the darkness. His stupid error may have killed people, and he probably feared mob justice.

I knew how he felt. Monica and I, though blameless, needed to get away too. Emotions would be high, and we could possibly be scapegoated as the nearest available targets. If nothing else, we'd taken inside seats that might have gone to Ethiopians if we hadn't been given respect as faranji.

The driver, compounding his mistakes, slammed shut the passenger door on his way out. I rolled my eyes and Monica knocked on the door, reminding the passenger outside that we were still within.

With an "oh right" look, the passenger lifted the hatch. I stuck myself under Monica to give her a boost, and then climbed out myself. I still had my loyal Manhattan Portage bike messenger bag attached to me. My passport, money, and guidebook inside were intact. Monica's small knapsack was also with us, as she'd been holding it in her lap when the Isuzu crashed.

Monica jumped off the truck, but the other passenger caught her ineptly, so when he offered to catch me I climbed down carefully.

We walked around the truck to a scene of chaos, lit by wavering flashlights. People and cargo were strewn everywhere, and everyone was screaming their heads off.

No one was trapped by the cargo or the truck itself, and it was impossible to tell if anyone was actually injured as everyone felt equally free to wail. I needed to find my pack, but worried that now was not the time to use my Maglight to hunt for luggage. My eyes adjusted and I spotted the bag. I wiped the specks of blood off it and shouldered the bag. I felt bad leaving, but the best way to help these people was to send an ambulance. The Band-aids, antiseptic towelettes, Dramamine, and Pepto-Bismol in my pack weren't going to save anyone's life. And clearly, the screaming masses were in no shape for the long walk to the Lalibela airport. It had to be us, and we'd be better off out of there anyway.

"We're going for help," we told Mendes. He nodded. The other passenger told us not to go - everything about this was illegal, and the police couldn't get involved.

"Too bad. We're going." We walked off quickly before anyone could stop us.

"We'll use one flashlight at a time to save batteries," I said. We had no idea how far the airport was.

"Right," said Monica, flipping hers on. She reminded me to drink water.

"We have to not go into shock."

We began a forced march, and both commented that we had little pains here and there. Mine was behind my left knee, in my left ribs, and along my left thigh. Monica's was in her shoulder. But we didn't want to stop and examine our injuries. Whatever they were, they could wait for us to get help and to put distance in between us and the emotionally charged crash scene.

Then, just before a bridge, a small old man appeared. He may have heard the crash, or the wailing, or he may just have seen a flashlight and two faranji coming down a deserted road at five in the morning.

I opened up my phrasebook to the "Emergency" section in the back.

"There's been an accident," I pointed out. "Danger, emergency."

"Eye-suzu," added Monica, while I pivoted my arm 45 degrees down from the elbow.

The man nodded and strode off in the direction we showed him.

As he went, he emitted several shrill yelps. A minute later, returning yelps echoed across the fields. People woke up and started the march over to the crash site. It reminded me of the "Twilight Barking" in 101 Dalmatians. He was raising the alarm. I thought it was pretty cool, but Mark later pointed out that "now there were just more people standing around staring."

Monica and I continued our walk, with me being amazed that I was able to carry my heavy pack so far without difficulty. Adrenalin was pushing us on, and giving me the ability to ignore the pain in my ribs and leg.

Finally, it occurred to me that it would do me no good to bleed to death. I paused and looked at my wounds. The back of my knee featured a deep puncture wound, but everything else was just bruised. Monica's neck was sore, but she was still moving. She'd impacted only against me, but I'd impacted against the gearshift, a plastic tray, a Coke bottle, and the driver.

We walked our forced march for an hour, passing Ethiopians en route to the crash scene, none of which seemed surprised to see us. There were no phones out there, but word had traveled quickly by yelp-telegraph.

After an hour, we reached the airport. A guard came out to greet us. I showed him my standard phrasebook lines, and the motioned us down the driveway.

"Hey," he yelled after us. We paused, thinking perhaps he needed more information.

"Cigarette?"

"No," said Monica, who had a pack of cigarettes in her pocket. What the hell was the matter with that guy, we wondered, slowing us down when people's lives were at stake?

A soldier wearing an AK-47 and a blanket approached us. We explained the situation. He woke up other soldiers, and action seemed to be taken.

"Call ambulance," I pointed out.

They nodded, but didn't move.

"Many people dead?" asked one.

"I don't know," I responded, wondering why they weren't springing into action.

One of them went somewhere, possibly to radio in the emergency. Or maybe he just went to pee.

"Two hours," said a soldier. Was that two hours until the ambulance got there? Two hours until the airport opened and we could get a ride out of there? Two hours until the local Red Cross office opened?

Then we realized the reason the soldiers weren't reacting. They had no vehicle, and there were no proper emergency services in Lalibela.

LALIBELA TO GONDER

NOVEMBER 14

Eventually, we did see headlights arrive at the crash site. It was probably the second truck in the convoy.

The soldiers escorted us into the closed airport and let us use the ladies' room. Both Monica and I had a brief moment of hysterical giggles before recomposing ourselves.

A minute later, we sat by the guardhouse, eating granola bars and using antiseptic wipes on wounds.

"Are you still going to Gonder today?" asked Monica.

"I have to," I mused. "But I'm not going to miss Lalibela after risking my life to get here."

I wondered too, what would happen if I had internal bleeding. I didn't want to be on a bus, truck, or Land Cruiser in the middle of nowhere if I suddenly needed medical attention. The absurdity of my massive travel insurance coverage now struck me. What was the point of being insured for all types of medical evacuation if there was no hospital, transportation, or communication? If I'd been seriously injured in the Isuzu accident, I would now be dead in spite of the nice promises the travel insurance company had made me. We'd been far from any cell phone network and an hour's walk from the nearest radio. And there was no ambulance or hospital once we'd found help.

Now, I decided, could be the time to use my third "plane" lifeline. What if I rested in Lalibela and then flew via Addis to Khartoum? But I had collected so much information on going from Ethiopia to Khartoum by land, and I really wanted to take up the challenge. What to do, I thought, what to do?

The answer presented itself. The airport staff bus pulled up, delivering the daily workers and throwing a young man named Liyu into my lap.

Liyu said we could ride back to town with the airport bus, drop off Monica at a hotel, see the churches and I could still make the noon flight to Gonder.

"Is that enough time for the churches?" I worried.

"I am telling you, that is enough."

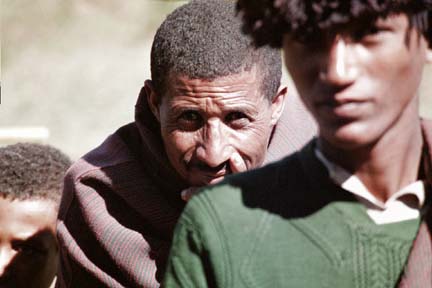

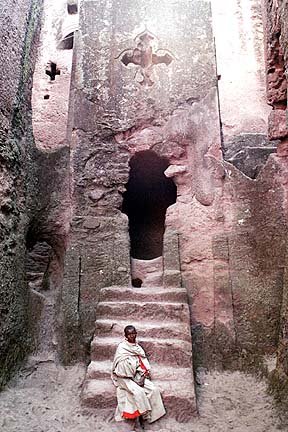

Lalibela monk

Lalibela monk

That was much better than flying to Khartoum. I'd only be backtracking by plane, not progressing. Gonder had modern medical facilities in case my leg ballooned up over the course of the day, and the Dragoman group would be there with Mark and Tony and their first aid training. Gonder was the jumping off point for Sudan, and Marie's World Tour would be more or less on track.

church under renovation

church under renovation

I accepted Liyu's offer. We sped into town, left my bag on the minibus and dropped off Monica at the hotel. She was carrying my goatskin lunchbox and a few of my souvenirs to Cairo, and I'd see her there on November 23. We promised to have a Big Mac together.

"Sorry I almost got you killed," I said.

pilgrim

pilgrim

"Don't worry about it," replied my partner-in-crime. Later she'd be hassled by Mendes for the second hundred birr, and finally paid it in disgust but her temper managed to frighten him in the process. She was in Lalibela for five days, and was known as the "faranji from the Isuzu." No one was killed in the crash.

Liyu took me to the Ethiopian Airways office, where I acquired a ticket. Then, we bought an entry permit and toured Lalibela.

inside a church

inside a church

The town center featured twelve rock-hewn churches, large structures carved right out of the volcanic tuff. The Guide to Ethiopia points out that were the churches "virtually anywhere but in Ethiopia, Lalibela would rightly be celebrated as one of the wonders of the world." They date to the 12th or 13th century, and their origins are the subject of some speculation. Popular theories hold that either a workforce of 40,000 constructed the churches, or perhaps freemasons from Europe. Most Ethiopians believe that angels constructed the churches, and Liyu was happy to espouse that theory.

Lalibela priest

Lalibela priest

Some of the churches were supported by rock columns, one was attached to an overhead rock, and others were freestanding monolith churches. Priests and pilgrims haunted the chapels, including Liyu's father.

dem bones

dem bones

Hideous tin roofs covered the church tops, protecting them from the elements. Liyu said there was a competition going on to determine the most aesthetically pleasing way to protect the churches. The tin was only temporary.

St. George's Church

St. George's Church

I was given a thorough but rapid look at the Northern Group of Churches. The guidebook had called Lalibela "Africa's Petra," and I could see why. Same ruddy color, same "carved out of rock" thing, and both inspired the same "how the heck did they do this" reaction.

St. George's from a distance

St. George's from a distance

The crowning glory was the Church of St. George. He is popular in Ethiopia, and St. George's likeness is everywhere. Only the Virgin Mary was more pervasive. Liyu dutifully pointed out the hoofprints that St. George's horse had made on the compound wall.

the roof forms a cross

the roof forms a cross

The church was carved right out of the ground and we had to descend to entry level by a set of stairs. The top was shaped like a giant cross. It was the most visually dramatic, impressive, and architecturally perfect of all the churches.

hoofprints of St. George's horse

hoofprints of St. George's horse

After my tour, I left behind St. George and King Lalibela and went back to the airport.

"You need at least three days to do the churches justice," claimed my guidebook. I hadn't even given them three hours.

carved from a single rock

carved from a single rock

Half an hour after getting on the plane, I was in Gonder.

I checked into the Circle Hotel. It had a shower, a terrace, and a TV. I wanted a bit of comfort and rest and was happy to pay the price. I examined my wounds.

They were hideously colored in shades of black and purple. My puncture wound was responding well to the antibiotic cream I had applied to it. My ribs hurt, but I could move. Nothing had swollen. I would head towards Sudan in the morning.

My local pals, Peter and Ababa, tracked me down quickly. Peter told me he had been praying for me and that had saved my life. I found the Dragoman group and told and retold the Misadventures of Marie and Monica. I left the Drago staff at night in the town roundabout, saying goodbye forever for real this time. We had an audience of about 15, including the three little girls who had braided my hair and one kid who shined my shoes. Somehow, in spite of the beggars, the touts, and shrieks of "youyouyoufaranji," Ethiopia had gotten to me, and I was going to miss it

NEXT: pain and vomiting in Sudan! Truck hitching without a hitch, and a visit to Gedaref's Ethiopian Compound.