Gorillas of the Bad Gas

(Marie-mail #55)

KAMPALA TO BWINDI

OCTOBER 2

I crept out of the decrepit backpacker's hostel before six a.m. The

minivan taxis were few and far between in the dark, and when a kid on a

motorbike stopped and offered me a lift, I happily accepted.

We stopped for gas -- everyone in this part of the world runs nearly

on empty, supposedly so that if their vehicle is stolen, it won't get

far. At six sharp, the motorbike left me at the edge of the bus park.

"Where to?" asked a Ugandan man.

"Butogota," I responded, whereupon he and four of his friends

cheerfully escorted me to the ancient "Silver" line bus.

the bus to Butogota

the bus to Butogota

I was the first one to board the 6:30 scheduled bus, and the second

person, who arrived 45 minutes later, was a tourist from Toronto.

"That's kinda like New York," I offered. After all, it was on the same

continent and not too far from home.

"How dare you?" she declared, appalled that a pompous New Yorker would

dare to besmirch her beloved hometown.

"Bitch," I thought.

The bus filled up eventually, and two young Slovenian women filled out

the tourists-off-to-see-the gorillas contingent.

An obnoxious man with a bowl of soup and a portable radio plopped down

next to me.

"To hell with being polite," I thought. "I'm moving." No way was I

going to spend the day next to a staticky transistor radio.

road to Bwindi

road to Bwindi

The man smiled and followed me to my new seat. He was intent on being

my seatmate for the duration. I should've sat next to the Canadian.

Mr. Charming tuned in -- more or less -- a sappy pop station (the only

option in Uganda save Christian broadcasting) at full blast. He

proceeded to spread his legs wide and poke me with his elbows. Butogota was

only eleven hours away.

The 6:30 bus finally pulled out at 8:45, its occupants half-dead from

inhaling diesel fumes in the bus park. We left the outskirts of

Kampala, passed an empty revival stage, and headed down the paved road into

the depths of Uganda.

bananas

bananas

The "Silver" bus, like most buses in developing countries, stopped

constantly. Bus stops did not appear to be set -- anyone with a flapping

hand was a potential bus stop. And there were none of those pesky safety

regulations to worry about either -- standing in the aisles was

perfectly acceptable, as was perching in the stairwell or hanging off of the

front door as the bus took off. And at every stop, peddlers would

approach hopefully, plying their trades.

Eventually, more people were standing than sitting. Mr. Charming fell

asleep, and two teenage boys reached over and shut off his radio.

A man got on with a bundle of new bicycle tires, which he stuck next

to my seat. A woman with a baby boarded and perched precariously on top

of the tires until Mr. Charming awoke and -- thankfully -- traded spots

with her. It was almost tolerable to be squashed by a mom and a baby,

whereas it was unpleasant to be squashed by a strange man.

The mom and baby disembarked just before we left the pavement for a

bumpy dirt road. They were replaced by a constant stream of chubby,

middle-aged friendly ladies, all anxious to welcome me to Uganda.

I have heard westerners comment that Africans have bladders of steel,

and I was inclined to agree with them. Buses stop only long enough for

passengers to embark or disembark, never long enough for a pee stop. I

have learned to risk kidney stones and drink nothing on these long bus

rides, but Ugandans seemed to drink anything put in front of them.

"You pray for a flat tire," one British guy in East Africa told me

later, "just so you can pee."

flat du jour

flat du jour

He was right, and fortunately flat tires occurred with astounding

regularity.

Our flat-tire-du-jour occurred in late afternoon, in a rural

semi-village next to a tiny tea shop with a doorless pit toilet out back.

Everyone -- even the Africans -- visited it with relief.

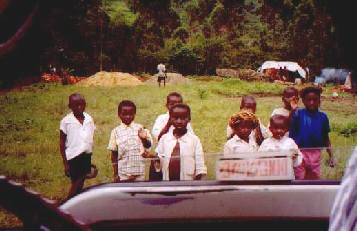

The local children gathered to stare, at the city people as well as

the pale foreigners. One child wore a Green Bay Packers shirt but had no

idea what it meant or why it made me giggle.

I wanted to explain to the kids why us four foreigners were standing

on a dirt road in rural Uganda. I found a photo of mountain gorillas in

my guidebook and showed it to them.

"Ngagi!" shrieked the children, first scattering in fear and then

crowding around for a better look.

Ngagi, according to "Gorillas in the Mist," was the Swahili word for

gorilla. I had read Dian Fossey's book in its entirety on the bus trip,

and wondered if she wasn't perhaps a bit compulsive.

A certain amount of madness, of obsession, is required for

single-minded tasks such as habituating gorillas. But that was okay -- I liked

slightly mad people. What concerned me was Fossey's skepticism about

gorilla tourism. It seems that strangers traipsing up to snap photos and

stare at gorillas can be stressful on out primate relations. Why, I

wondered, was I here if it was stressful on the gorillas (and expensive to

boot)?

The answer is easy. There were 242 ngagi in the mists left in the

early 80's when Dian Fossey started her research. Today there are over six

hundred. This is certainly due to public awareness and support, and

gorilla tourism. Tourism is big business and at $250 hard currency a

visit, plus ancillary income from visas, hotels and transportation, the

mountain gorillas were a cash cow worth protecting.

"Would the mountain gorilla be a species doomed to extinction in the

same century in which it was discovered?" Dian Fossey had asked this

disheartening question in her book. The answer, we now know, is no.

Our flat repaired, we left behind the squealing children and headed

out into the drizzle.

I had planned carefully to avoid rain in Africa but the weather was

off schedule this year. The muddy roads made for slow going but we neared

the outskirts of Butogota around 7:30.

And then our lights cut off. The electricity on the bus shut down

entirely. The road in front of us was pitch black.

Our driver sensibly applied the brakes and didn't steer left or right.

There was no panic, and the bus staff used flashlights to repair the

damaged wire or fuse.

We started up again, with a renewed sense of confidence in our driver

and a better idea of the real safety concerns of using local transport

in poor countries. If the driver hadn't maintained his cook, I realized

that we could have been in a dangerous situation. Two months later, in

Ethiopia, I was to learn just how dangerous.

We finally stopped in Butogota, where a pickup truck waited to take

the Slovenians and I to Bwindi. The Canadian was resting up for a day

before continuing.

banda

banda

The last seventeen kilometers took forty minutes, and finally,

exhausted, we checked into a cement "banda" at the Community Restcamp. The

friendly staff served us spaghetti by candlelight and gave us a bucket of

water to wash the day's grime from our sweaty bodies.

I caused a minor uproar by refusing to write my home address or

nationality in the register. The murdered tourists in '98 had been Americans

and British nationals.

"Do the gorillas ever come to the camp?" I asked the kid who worked

there.

"Sometimes they come to see us. They wander into the yard. I am sure

that they know me."

The Slovenians and I retreated to our banda. By lantern light, we

locked the door. I was glad there were bars on the windows, and that I

wasn't sleeping in a tent tonight.

BWINDI TO KABALE

OCTOBER 3

I could hear rain pounding on the banda's tin roof. That meant that I

had survived my night in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

I opened an eye and squinted at my Timex Indiglo watch. It was five.

Time to open the other eye and get out of bed.

Reading the Dian Fossey book had brought an air of excitement to my

visit, and I now understood that I was going to see a rare and unique

endangered species.

ready to track gorillas

ready to track gorillas

After breakfast, we paid our National Park fees of fifteen dollars

each and were split into two groups. The Slovenians were off to visit "H"

group, and I was to see "M" group. I was lucky -- traipsing through the

jungle was tough, muddy going and "M" group was currently rumored to be

close to camp.

The Slovenians, however, had a tough day ahead of them. Yesterday's

"H" tracking group had returned after 5 p.m.

I joined what turned out to be a group of five. One woman worked for

Mantana, a Ugandan travel outfitter, and she had her US marketing rep

(http://www.eaiadventure.com) along. A South African woman was single

for the day, as her husband had to split up and go with the "H" trackers.

And the other two -- Jordi and Nuria -- were an adventurous Spanish

couple on a two-week Ugandan holiday.

We all got walking sticks and a briefing.

Luz was our guide. He was accompanied by two expert trackers, three

porters (I carried my own bag), two armed guards, and one Ugandan

university student whose job it was to record precisely everything the

gorillas did. Uganda seemed to have great pride and scholary interest in its

gorillas. Gone were the days of indiscriminate poaching and trapping.

We were to follow along, quiet and non-threatening. If a gorilla

charged us, we were to kneel down on all fours and submissively look at the

ground.

guess what? gorilla butt!

guess what? gorilla butt!

"And pretend to eat grass," I added silently. That was what

cartoonist

Peter Kuper was told to do in Rwanda some years back.

Perhaps the grass-eating had been discredited as overkill, or perhaps

the guides had just gotten tired of being laughed at by tourists. We

were sent off gorilla-tracking without these vital instructions.

We set off down a dirt track. We could hear troops drilling just to

our right, behind some brush. That was the "invisible army" I'd read

about. Rumor had it that Rwanda guards followed the gorillas around

constantly to protect them from Congolese rebels -- modern-day poachers whose

aim was to damage the economy of Rwanda.

Our trackers led us up a the dirt road for ten minutes, then took a

startling right turn into a dense jungle of mud and undergrowth. I

wondered now at the wisdom of not hiring a porter.

It was the "impenetrable" bit of "Bwindi Impenetrable Forest" that

should have tipped me off. The rain, mud, and vegetation was impenetrable

enough, but the massive slopes complicated the trek. I leaned heavily

on my walking stick, poking it into mud and putting all my weight on it

as I propelled myself up jungle hills.

Ex-Dragoman driver Nikki had warned me to bring an old pair of

gardening gloves "as you must sometimes haul yourself along by vines and

roots."

I hadn't brought gardening gloves, and just as I was beginning to

regret it, we started sliding back down hill towards the road.

hiking through the forest

hiking through the forest

Our uphill escapade had been in vain. The trackers followed the

gorilla trail to the left of the road this time.

Later, I suspected that the trackers had deliberately taken us

off-course, to give us a taste of tracking, so we wouldn't feel cheated at

having missed our chance to wallow in mud.

Group "M" was only fifty feet from the road. We all left our sticks

against a tree and got our cameras ready.

"Look, he's mating," said Luz.

Excitedly, we all crowded forward to see the dominant silverback at

work.

"That's it?" I thought. The silverback sat passively, a bored

expression on his face.

The flattened female gorilla under him looked more like a gorilla-skin

rug than a living breathing mountain gorilla. I'd expected noises or at

least movement. Perhaps we'd just seen the end.

We had. The silverback -- presumably they're named for the silver

stripe adult male mountain gorillas develop -- stood up and casually

strolled away. He seemed to be utterly oblivious to our presence, but more

than likely considered us no threat to his group of twelve.

His name -- which I've forgotten -- meant "sleeps a lot." But

Sleeps-A-Lot didn't sleep today. He posed for a bit, taunting my high-speed

film as I realized that even 1600 was not fast enough for the low light.

Then he joined his family up in the trees, where they searched for

fruit.

We couldn't see much of the gorillas, and I was getting worried. The

permit guaranteed us an hour near the gorillas, but not within sight of

them. If the gorillas chose to stay in the trees for the whole hour,

that was their perogative and our tough luck.

Perhaps, I thought, we couldn't SEE the gorillas, but we could

certainly hear them.

"FZZZZRRTT!" The silverback let one fly.

"BRRRRRZZZT!" So did the female he'd been squashing earlier.

We spent forty minutes listening to gorillas farts.

"Do they always do that?" I whispered to Luz.

He nodded. "They are vegetarian."

Funny, Dian Fossey never mentioned gorillas gas in her novel. Maybe

she was so accustomed to it that it didn't merit so much as a mention.

Finally, the gorillas descended. The biggest, Sleeps-A-Lot, was about

half my size and the others were small and squat. Their funny shapes

didn't impede their agility, however. The gorillas -- for the most part

-- gracefully propelled themselves earthwards by using branches and

vines. They seemed to exert no effort at all. A few of them were less

graceful, and nearly plummeted to the ground. It was gorgeous to watch --

twelve fat little apes descending as one.

"It's been one hour," said Luz. Reluctantly, we plowed through the mud

back to the road.

happy gorilla trackers

happy gorilla trackers

My goal was to get to the town of Kabale -- three hours away -- by the

end of the day. If I could get over the difficult mountains now, I'd

only have a six-hour bus ride to Kampala tomorrow.

Jordi and Nuria, fortunately, were headed that way. Their driver

agreed to take me along, and after a quick lunch we headed over the

mountains to Kabale.

The ride was rainy and beautiful, as the bad road wound its way

through the mist past terraces and banana trees. Our driver was safe and

considerate, and made way for the kids, goats, and bicycles on the road.

local kids

local kids

When we got to Kabale, it was pouring. I offered to stay at the

expensive hotel in town as it was the easiest place to drop me off. But the

driver insisted on taking me to Sky Blue, a cheap and friendly hotel

where I was the only tourist. I had a simple room with a bed and a look,

and there was a hot shower nearby.

KABALE TO NAIROBI

OCTOBER 4

I had to wake the manager to let me out at six a.m., and then had to

sit through the incomprehensible stories told to me by the gun-toting

guard. Eventually, a modern bus came by. I boarded. Everyone left me

alone, and in six hours I was in Kampala, where I boarded the 3 p.m.

overnight bus for Nairobi.

yet another flat tire

yet another flat tire

NEXT:by balloon over Masai Mara and a week in the terrorist hotel in

Nairobi.