Zanzibar Gloom

(Marie-mail #51)

DAR ES SALAAM TO ZANZIBAR

SEPTEMBER 11

I was out of my room and up at eight, waiting for the Safari Inn's internet cafe to open.

It finally opened at a quarter to nine and somehow three others who had arrived after me were chosen to go first. I sat waiting until 9:30. I'd never waited and hour and a half for the internet before, and resolved to not return to Safari Inn after my trip to Zanzibar.

I gave up and walked towards the port.

"Jambo," said a taxi driver, brightly. Officially, "jambo"

means "hello" in Swahili. But to tourist in Tanzania, it means "look

at me, I want to sell you something."

I have received e-mails from people who are shocked that I am not more

tolerant of the innovative methods employed by local entrepreneurs in

their attempts to part me from my cash. To them, I say "trust me, if your

daily routine included being accosted forty times an hour every time you left

your residence, you'd tire of it too." And while sellers have a right to

come up with clever ways to engage me, I have an equal right to try to outsmart

them.

Smile but be firm and eventually "jambo" will just be background

noise.

streets of Zanzibar

streets of Zanzibar

The catamaran was full of a mixture of locals and overland truck

tourists. I had a Coke and cookies for breakfast -- there wasn't much

of a selection on the ferry.

On the Zanzibar side, touts dogged me all the way from the port to the hotel.

"Listen," I said. "I already have a reservation, so you're wasting

your time. You're not getting a commission for a pre-booked room."

Nevertheless, one of them persistently followed me the whole way to

Emerson and Green Hotel, an

atmospheric hotel dubbed "one of the best small hotels" by London's Sunday Times. It was a splurge for me, even though I'd gotten a discount and taken the

cheapest room.

Kipembe suite at Emerson and Green

Kipembe suite at Emerson and Green

The bellhop showed me around. It was an old mansion, and each room (or

suite, really) was individually decorated with antiques, tiles,

hardwood, and ceiling fans. Legend had it that Emerson and Green had been the second tallest building in town, and the dinners on the rooftop terrace are legendary. I booked myself in for that night's dinner and went for a walk.

Kipembe suite at Emerson and Green

Kipembe suite at Emerson and Green

The tiny alleys reminded me of Damascus or Jerusalem. Barely three

people could walk side by side, but that didn't stop motorbikes,

wheelbarrows, and small vehicles from plowing down the walkways. They were a maze, with no discernible pattern, and I would have been lost without my map. Most of the ground level dwellings were storefronts, many of them selling souvenirs and tours. Much is made of Zanzibar's Arabic population and Middle Eastern feel, but it is unique because it is also very laid-back and African.

I stopped in at an internet cafe, checked my mail, and walked out into the main lobby to pay.

The tv was on. CNN was on. Two very familiar buildings were on tv.

They were on fire.

It was a rhetorical question, really. I just needed confirmation that

I wasn't insane.

"Is that the World Trade Center?" I asked shakily.

The two kids who worked at the internet cafe nodded and giggled. They

thought it was funny that two giant skyscrapers were on fire.

"A plane hit it," they said with apparent delight, and then noticed my

expression. "What's wrong?" asked one of them. I had probably gone

pale.

"That's an office building," I said. "Lots of people work there."

The kids quit giggling.

"How many?"

"Thousands, THOUSANDS," I replied.

Other tourists that happened through stopped and stared. Two were

Americans, and one of them, a young woman from Los Angeles, was as

teary and whimpering as I was.

But we'd seen nothing yet, of course. The Pentagon was hit too, and

false reports had us thinking that fires and carbombs were going off

all over northwest DC.

At home, Yancey watched live from the river as the twin towers

collapsed, damaged in their steel cores, their metal frames unable to

sustain their weight.

"I've never seen anything more horrifying," e-mailed Yancey, just

before he went to give blood.

Other friends saw it from their roofs, and watched soot-covered

business people trudging northward throughout the day. My entire

neighborhood was closed down, and fresh food couldn't get in for days. One of my friends, Larry Hama, lives just a few blocks north of "Ground Zero." He was volunteering at the election polls that morning and watched the second plane approach, alter its course twice, and then plow into the south tower. He reported expensive women's shoes lying on Broadway, deserted by fleeing owners. He and his wife walked north for miles, carrying their dog, and had to stay with friends in Queens for weeks. He now lives with the reality of possible airborn asbestos, freon, and toxics from burning plastic.

I knew none of this at the time... all I knew was that for the first

time, my mother sent me an e-mail that she was happy I was in Africa

instead of home in lower Manhattan.

People from all over the world stared at CNN with me, shook their

heads, and grieved over the loss of innocent lives. Local Muslims were

as distressed as tourists. There was no anti-American sentiment this day

-- that came later -- for the moment, nationalities were forgotten and we were

all simply human.

Eventually, no one was crying anymore, and people were laughing

nervously -- in that way that people do when they don't know how to

behave. CNN's live broadcasts took on a cinema-esque quality, and we adjusted

slowly to the idea of a new world order being a possibility the next time we got out of bed. Friends e-mailed me with worries of World War III, and I developed alternate plans of evacuation, escape, and self-imposed exile, all

depending on the next moves by the U.S. government.

I went back to Emerson and Green and begged off of dinner. I couldn't

tear myself away from the news.

Vicki and Mubiana tracked me down through my hotel, and offered their

company. I was glad to have it, and we worried about the state of the

world together.

Finally, at ten o'clock at night, the internet cafe closed. I moved

next door to a hotel lobby, and watched silently some more, before CNN

was just repeating itself. I walked back towards Emerson and Green.

"Jambo," said a dreadlocked man in a suit, keeping pace with me in the

dark street.

"Hello," I said, quickening. He kept up.

"I would like to talk to you. Remember when you said we could talk.

Every time I see you, you are busy."

"Sorry, you're wrong." I had little patience for tout games this

evening.

"You don't remember me..?" I cut him off, knowing the rest of the

sentence, which would be "from the hotel," after which point I would

assume he worked at my hotel. After gaining my confidence he would try to sell me something or borrow a small amount of money.

"That is impossible," I said firmly. "I have just arrived."

He faltered and fell back on an old standard.

"Where are you from?"

"NEW YORK CITY," I said. "Lower Manhattan. I am not in a very good

mood today.

He stopped, leaving me to finish my walk alone.

ZANZIBAR

SEPTEMBER 12

My sleep was fitful and I woke up early.

I took the destruction of the World Trade Center very personally.

Probably most New Yorkers did.

But at least I was in a beautiful hotel room, instead of in the hell

of my closed down, smoke-filled neighborhood. My small "kipembe" suite

consisted of three rooms, decorated with antique furniture. I had the Emerson and Green's breakfast of breads, fruits, and Zanzibar coffee on the rooftop

terrace.

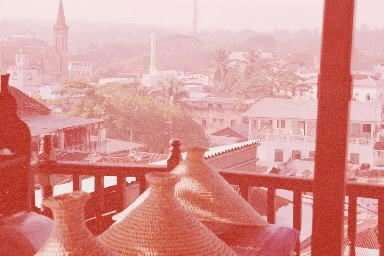

from the terrace at Emerson and Green

from the terrace at Emerson and Green

I went to see the town, but made the mistake of stopping by a

television first to catch up on the news.

An hour later, depressed, I tore myself away. The havoc in NYC was

grim, and I no longer cared that I was in Zanzibar. I spent the day

watching CNN and reading updates on the internet.

I also toured several small hotels. E&G was fantastic, but I couldn't

afford even a single night there and was being horribly irresponsible

by spending my money on it. The E&G cook had a cheaper guesthouse that

looked lovely but was still prohibitively expensive. The cheap hotels were

mostly shabby and disgusting. I wasn't sure what I would do when I left E&G.

I had an unexpected problem of being prone to sudden bouts of

weepiness. People were beginning to stare, and I couldn't very well

turn around

and tell them that if their city was in tatters, they would be upset

too.

At six, I met Mubiana and Vicki for a drink on E&G's terrace. The view

was nice, as anticipated, but the real charm was in the audio.

Vicki and Mubiana

Vicki and Mubiana

The call to prayer sounded from dozens of nearby mosques, and the

jangling bells at the nearby Hindu temple provided a suitable

multi-cultural accompaniment. Together with the conversation, I managed to take my mind off the tragedy at home.

But I'd have to watch events closely. When the inevitable retaliation

started, it could affect my route north. It was even conceivable that I

could end up stuck abroad.

SEPTEMBER 13

I moved to an airy top-floor room at the Karibu Inn for $15 a night.

It was no Emerson and Green, but I'd seen dozens of disgusting budget

hotels. Karibu was the best of the lot.

the house Freddie Mercury was born in

the house Freddie Mercury was born in

My Greek friend Thanos e-mailed me to remind me of a professor we'd

had in college. Will Roberts used to put his tv in the corner when it was

bad, and both Thanos and I now understood what he'd meant. The news had become

repetitive and desperate, and was becoming less relevant. The Onion

said it best: "Woman, not knowing what else to do, bakes American flag cake." I

understood her motives. No one knew how to act or what to do. Not being much of a patriot or baker, my solution was to stare at CNN, or wander the alleys of

Zanzibar in a daze.

The e-mails I got from home were startling. It was as if all my

friends had suddenly woken up that morning and decided to try to write thriller

novels. But of course the events they were reporting were not novice attempts

at fiction. They were all reporting their personal experiences. Offices

were closed, work had been brought to a standstill, the Captain America

artist had temporarily stopped drawing in despair, and planes were grounded.

Debris littered downtown Manhattan. The revolving door I'd once anonymously

shared with Lady Miss Kier of Dee-Lite at the CMJ convention was gone, along

with 6,000 people and Lower Manhattan's most reliably clean public restroom.

I outlined contingency plans in an e-mail home. There was the "get

home ASAP" option, the "stay put and lay low" option, the "bat out of hell

to South Africa" option, and the "ship to Australia" option. I still hoped to

continue my trip, which called for me to go overland through northern Sudan, but wouldn't be able to make a decision for some time. Perhaps I could

disguise myself as a Muslim woman.

Zanzibar shore

Zanzibar shore

I sat by clear, aqua-colored seas, in an open-air restaurant under a

ceiling fan. There was no enjoying Zanzibar, I reasoned, and it was

expensive. I was miserable, and changing locations wouldn't help that. But at

least if I was going to be moping about, I could do it somewhere cheaper. I'd go back to Dar tomorrow. I'd be closer to the airport in case things went horribly wrong, and there would be fewer men saying "jambo, blondie, what are you doing tonight?"

ZANZIBAR TO DAR ES SALAAM

SEPTEMBER 14

I woke up under my towel. One thing I hadn't noticed when I'd checked

into the Karibu Inn was that it didn't supply top sheets or blankets.

I'd left my camping gear back in Dar, but my towel had been enough in the

tropical climate.

I successfully avoided touts all morning, and walked to the port to be

stamped out of Zanzibar.

Zanzibar is part of Tanzania. It's the "zan" in Tanzania. But

bizarrely, tourists must fill out forms and go through Immigration on

the way to and from Zanzibar. This seemed silly to me, so I inquired as to its

purpose.

Zanzibar colonial building on the waterfront

Zanzibar colonial building on the waterfront

"This way we know how many tourists we have," explained a patient man

at Tourist Information. I wondered why they couldn't just count foreigner-priced ferry tickets, but left the topic alone.

DAR ES SALAAM

SEPTEMBER 15

The Luther House Hostel didn't appear to have hot water.

I'd been delighted with the hotel yesterday -- or would have been if I

had been in any state to be delighted. Luther House Hostel was much

nicer than Safari Inn, and had a terrace with a seaview.

But like the Safari Inn, it was shabby. I wanted comfort and

familiarity -- I wanted to go home, but couldn't now even if I had

seriously tried. Air traffic was chaotic, and flights were booked for days. The

best course of action, I'd decided, was to stay put, learn the flight

schedules, and pay attention to the news.

The reports from home alternated between bleak and optimistic,

depending on who was giving them. One of my editors said that "the

rhetoric of war is everywhere" and mentioned anti-Arab hate crimes were increasing. My mom thought it was calming down. Some wanted to find and prosecute the perpetrators while others asked for quick, violent revenge.

Taxi drivers and touts, attracted by my obvious "foreignness,"

cheerfully tried to snare me with cries of "jambo, where you from?" I

wanted to smack them, throw a tantrum, or maybe sit down and bawl. How could they be trying to sell me a trip to Zanzibar? Didn't they know we were in the

middle of a massive world crisis?

I ate lunch at Subway, dinner in a food court, and watched BBC in my

new hotel lobby (I'd switched to "Econo Lodge" after looking at several

hotels). Could I really just casually go on safari? But then, what

choice was there? Mope about in a crummy hotel or mope about with lions. I'd still be miserable on safari, but at least it would be someone else's

responsibility to feed me.

SEPTEMBER 16

"Jambo," said a man, keeping pace with me as I left Econo Lodge.

"Jambo," I muttered.

"What do you do today? Go to Zanzibar?"

"No."

"Tomorrow?"

"Already been."

"Safari then?"

"No. Goodbye."

"Goodbye" didn't always work, but it often gave them pause, and I'd

take advantage of the moment to walk away briskly.

"Jambo," said a handicraft seller. "You look nice. Can I talk to you?"

I managed to disavow him of this notion, and shook him after being

thoroughly rude. I ate at Subway, drank coffee at the Sheraton, and

took comfort in the familiar.

SEPTEMBER 17

The disaster at home was becoming part of my reality, as it was part

of the world's. I wasn't "over it," but I caught myself smiling at taxi

drivers instead of averting my eyes and looking downcast.

The world had changed. But I was going to try to continue if I could.

I'd had e-mails from home supporting my decision to forge ahead. There

was certainly no point in returning to New York at the moment.

I bought "The East African" newspaper and noted with dread that the

front page was devoted to the possibility of the US bombing Sudan. That

wasn't something I wanted to hear.

Inside, a variety of editorials made points (valid or otherwise) that

were not yet being made at home. One editorial suggested that Americans

had fancied themselves "divinely protected," and assured readers that

Americans had "xenophobia rooted in the political ignorance of even many highly

educated Americans."

"Yeah," I thought sarcastically, "and the rest of the world is so

politically sophisticated."

A professor was quoted as attributing it all to an egregious imbalance

of wealth. I was going to have to watch my back as an default participant in

the world order. It was all madness, as Charlton Heston pointed out in

the "Planet of the Apes," a movie that suddenly seemed very relevant.

We were all being reduced to primal urges and xenophobia, and the chimpanzees

can only watch the horrors unfolding around them, even in the high council,

which is somehow complicit in it all.

One columnist pointed out that Iran society was a microcosm of the

battle of conservative versus progressive Islam. He was right -- when I

was there in '98, the forces of progress (Khatami and the moderate left) were fighting for social change against mullahs and conservatives. Although it must be said that Iran, at its most conservative, never forced women to give up working and wear screens over their eyes, the way they must in a few countries.

Another columnist mentioned that people don't deserve death for the

crime of being wealthy, and another worried that justice would take a

back seat to politics.

Still another begged American to not let Israel's battles influence

its own, and asked the US to work with Malaysia, Pakistan, Egypt and the

Saudis to solve the terrorism problem.

And finally, one editorial pointed out that the US had not intervened

when 800,000 Rwandans were killed. Which explains why those around me

though the World Trade Center collapse was a sad story but might as well have

happened on the moon. Lower Manhattan was a world away, as far as Rwanda was to

us when the Hutus and Tutsis went at it in 1994.

I bought instant oatmeal, peanut butter and jelly, bread (which I

watched get sliced in a bread slicing machine), some pastries and a

Coke. My standards had slipped a long time ago, and I considered this a treat.

DAR ES SALAAM TO ARUSHA

SEPTEMBER 18

I got up at six. The toilet still flushed intermittently, there were

still cockroaches in my room, and the ceiling fan creaked. But Econo

Lodge was much nicer than Safari Inn, Luther House, or the Starlight Hotel I'd

looked at. It was too early for hotel service, so I substituted a Coke for coffee and bread for breakfast.

I caught a taxi to the Scandinavian Express bus station. They were

reputedly the safest and best bus company, and if nothing else at least

had their own station close to the center of town.

Along with a few Africans and five tourists, I boarded a "luxury" bus

filled with mosquitos, and started the nine hour trip to Arusha.

The bus started up. The a/c came on. A cockroach fell on me and we

were off.

The bus hostess -- commonplace on buses outside the US -- called ahead

to Arusha and lined up a ride for the tourists on board. The ride was a

safari company's Land Rover, who first suggested we use their services and

then took us to a friend's hotel. Fair enough -- the ride was free, so they could get a kickback. And the friend's hotel -- Arusha Centre Inn -- was less than ten dollars a night for a shabby en suite room with hot water.

I checked in and immediately set out to find a better place. I was

pleased that only two people tried to sell me stuff as I walked through

town. Arusha has a terrible reputation for persistent touts.

After visiting a few hotels that were three times the price but only

marginally better than the Arusha Centre, I booked a night later in the

week at "Mezza Luna," a pleasant and friendly Italian restaurant/hotel. I'd

stay put for now, for the sake of my budget.

Back at Arusha Centre Inn, I discovered that, like everywhere else

from Lusaka northward, it was infested with the common German cockroach.

East Africa, land of the lion, the cockroach, and the nose-picker, I

thought. When I wasn't busy smashing cockroaches, I'd be inadvertently

watching someone with their finger up their nose. No problem, I thought, I'd

find a new hotel tomorrow.

ARUSHA

SEPTEMBER 19-20

Obviously, I'd gotten soft. The Belgians in the next room like the

Arusha Centre Hotel just fine. I'd eaten only western food for a week,

and had pancakes and coffee for breakfast. Perhaps my latching onto the

familiar was some sort of grief process.

I had fresh Tanzanian coffee at Jambo Coffee House, a friendly place

decorated with six-foot tall wooden giraffes and happy coffee pots, and

went to find a cockroach-free room.

"New Safari Inn" was all right and had the added bonus of having

housed Hemingway. "Hotel Equator" was outrageously expensive. "Mashele" and

"Meru House Inn" may have been okay, but they were not centrally located.

"Arusha Naaz" was good and twenty dollars a night. "Outpost" was all right but

overpriced for what it was.

Somewhere along the way, I realized that it was stupid of me to spend

all this time looking for a room when I knew that Mezza Luna was nice,

so I went there and checked in two days early.

The staff at Mezza Luna was exceptionally cooperative. They were happy

to do my laundry, excitedly told me that breakfast was included with

the room, and laughed when I asked about the safe deposit box.

"It will be safe in your room," said the receptionist smugly.

I left Mezza Luna and walked down a busy, tree-lined road to the town

center. Instead of the usual greeting "jambo would you like to buy..."

the locals on this end of town went about their daily lives. Children

walked to school in uniforms. Teenage boys in red and black checked Maasai

blankets walked by in high-tech running shoes. A soccer game was in progress

nearby.

"Karibu," said everyone who passed me. It meant "welcome" in Swahili,

and in Arusha everyone said it non-stop. One African teenager who said

"karibu" was dressed in baggy jeans, running shoes, and a floppy hat. He was the spitting image of an African-American teenager -- influenced by styles

that in turn had been influenced by African culture of over a hundred years

ago.

I was in a pretty good mood until I picked up a newspaper. Then I

discovered the anti-American backlash had begun in force.

The initial shock and revulsion had worn off, and today's papers were

filed with editorials sniping at the US.

Some believed it was time that American got a little of what it dishes

out. Others welcomed the promised land to the "real" world, and others

claimed that U.S. policy had provoked this.

This incensed me. America has made its share of mistakes and certainly

has a lot to answer for on a global scale, but no one who got up on

September 11 and went to work at the World Trade Center or boarded an airplane

bound for the west coast had anything to do with policy-making.

When I was younger, I thought that "by any means necessary," had a

point. I had been different and the world had been different. Now I

thought that was a lot of crap. It had gotten the Palestinians and Israelis

nowhere, and would only result in more violence and the closing of an open

society.

Was it possible, I wondered, to begin a constructive dialogue between

rich and poor countries out of such a misguided, tragic action?

I took myself out for Ethiopian food on my last night alone in Arusha.

This was a first for me -- eating Ethiopian food is something you do in

a group, unless you are Ethiopian. But I'd gotten brave about going solo,

and no longer cared if I looked like a loser.

To my surprise, there was a photo of President Clinton on the wall.

The restaurant had catered a dinner for the President when he'd visited

Arusha. This was the third place I'd eaten at that had fed him, and I'd also

seen his photo in Guatemala and his wife's photo in Istanbul. Surely there was

somewhere I could go that "billsworldtour" hadn't gotten to first.

The restaurant owner told her helper to escort me home. Fortunately,

Mezza Luna was only a short walk away.

NEXT: on safari with Guerba! The Serengeti, Ngorongoro Crater and tree-climbing lions.