Curios and Currency

WINDHOEK TO VICTORIA FALLS

AUGUST 18

I awoke crammed into a bus seat, just in time to see a bright red orb pop up over the eastern horizon. The bus stopped at Divundu, the westernmost town on the infamous, misunderstood Caprivi Strip. We had to wait for a convoy and military escort.

In mid-1999, some rebels attempted to seize a town on the Caprivi Strip -- the thin branch of Namibia that divides Botswana from Angola and Zambia. The Namibian Defence Force reacted strongly, intimidating and scaring tourists with their zealous anti-rebel tactics. A few people were inadvertantly shot. Two years later, motorists must still transit through the region with military escorts.

Soldiers with machine guns patrolled our convoy, occasionally zipping past on Jeeps.

We were given back bus self-determination at Katima Mulillo, and crossed the border into Botswana.

The Botswanans didn't look for my Namibian exit stamp in my passport, and I was finally able to switch back to using my "real" passport.

Our route took us straight through Chobe National Park, and I watched baboon, zebra, and vultures out of the bus window.

Out of Namibia. Into Botswana. Out of Botswana. Into Zimbabwe. We were crossing a lot of borders that day.

Lars and Carina got a nasty surprise at the Zimbabwe border. They had to get visas.

Swedes are almost universally liked, and seldom must pay for visas. My guidebook specifically stated that Swedes do not have to pay for visas in Zimbabwe.

Unfortunately, the rules changed in April. Zimbabwe is in a currency crisis, and free visas were now a think of the past.

Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls

The border accepted US dollars and South African Rand only. Namibian and Zimbabwean dollars were not accepted. That was all that Lars and Carina had.

To complicate matters, the border money changers had the same rules. Namibian dollars were just pieces of paper here. Which is actually all any country's bills are, but we have all agreed to universally hallucinate that the US pieces of paper are worth more than the paper they're printed on, so to speak.

I loaned my Swedish pals the necessary US paper, and we proceeded on to Victoria Falls, to a future of certain touts and money changers.

We got off the bus and walked to "Club Shoestring," the local backpacker's hotspot. It was chaotic, crowded with partiers and overland trucks, and had cockroaches. Too lazy to continue, I checked into a dorm. Lars and Carina, ever the intrepid explorers, plowed ahead, visiting other guesthouses and settling on a room with an en suite bathroom at "Pat's Place" for a measly seven dollars a night.

We agreet to meet later for Wimpy burgers, and I had a hot, comfortable Shoestring shower.

I went downtown to use the internet and encountered the full-on Vic Falls experience.

Zimbabwe, as everyone probably knows, is having problems at the moment. And while I wasn't well-versed in the politics of the country, I was immediately schooled in the local effects of the currency crisis.

Officially, 55 Zimbabwe dollars are worth one US dollar. The government has made this the rate, in an effort to prop up its ailing currency.

Unofficially, one US dollar equaled (and has since gone up even more) 250 to 300 Zimbabwe dollars and there was no shortage of people anxious to trade with me.

"Change money, change money?" came the furtive whispers from young men on the street, interspersed with occasional "safari" and "gange" calls.

After scarfing down Wimpy burgers, Lars and Carina signed up for whitewater rafting with "Safari Par Excellence," while I arranged a horseback safari. They left me at Shoestring's, where a Dragoman group was partying hard to celebrate their last night together.

I was tired from the bus and in bed by eleven, but the partying music at the bar -- just on the opposite side of the wall from my head -- continued until late.

VICTORIA FALLS

AUGUST 19

I hated Vic Falls and Club Shoestring was a hellhole.

Dozens of drunk overlanders had partied hard into the night. Other overlanders were up early, prepping trucks for departure.

I climbed out of my top bunk, waiting in line for one of the three toilets for ten minutes. I then discovered that Shoestring's had no breakfast and most of the cafes in town were closed on Sundays.

I walked to town and was accosted on all sides by money changers and touts.

"Good morning," stated a man, waving a fistful of necklaces in my face.

"No thank you," I replied.

Another man picked up his pace and walked alongside me.

"How are you?"

"No thank you."

"I'm just trying to be friendly."

"No thank you."

He gave up, but three more men were waiting another ten feet away.

"Change money," hissed the first.

"Good morning just my size," said the second.

"WHAT??" I stopped, appalled.

"Uh..." The second man hesitated. The third just smiled at the discomfort of his friend.

I turned down Livingston Way. A man followed about six feet behind me.

"Sssst," he said.

"Sssst."

"Sssst." Surely he'd get bored.

"Sssst."

I spotted three uniformed policemen up ahead and decided now was a good time to stand up to the steaming tea kettle man.

"What is your problem?" I turned around and glared.

"What? No problem."

"Then why don't you stop?"

"You should be more polite," he lectured me.

"You could be more polite too. Sssst! Sssst!" I turned away and walked on.

"Good morning," said one of the policemen, laughing.

I walked into "Zambezi Blues River Cafe," where a nice man presented me with eggs, toast, sausage and fresh coffee. Victoria Falls wasn't all bad.

Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls

Zimbabwe was, not long ago, the model African country, a real success story. But the Mugabe government's attempts at land reform had so far had disatrous results. It wasn't the actual land reform concept that was the problem -- it was the execution. Fair compensation for returned land had been given lip service but had not happened; the end results had been violent. International businesses pulled out of the country, followed by a hard currency crisis that brought on fuel shortages.

Three travelers from Shoestring's joined me for breakfast. One, an Italian, had been to just about every country in Africa.

"Have you been to Sudan?" I asked excitedly. I was considering going through northern Sudan to get to Egypt en route to Europe.

"Yes," he replied. "And I was in jail within three hours of crossing the border. I don't know why -- just because I was a foreigner and they wanted to know what I was doing there."

That wasn't very promising.

A few hours later, I was more forgiving of Vic Falls. I'd found "Savanna Lodge," right up the road from Pat's Place, and I moved into a ten dollar a night room. The help was organized and well-informed, the bathrooms were clean and not overrun with overlanders, and the second night was free with my "Nomad Tours" trip.

I made my way to the town curio market, where the bargains were amazing. Unfortunately, I had no idea if the Zimbabwe postal system was reliable, so I bought sparingly. No point in buying wooden six-foot giraffes if they weren't going to make it home.

I stopped by the internet cafe to check my e-mail. Access in Zimbabwe was painfully slow, and the girl sitting next to me was reading a book concurrent with checking her mail.

Then it was on to my Zambezi Trails horse safari. Apparently, something got screwed up with my booking and I was picked up a half-hour late. The other riders were all departing when I pulled into the stable parking lot.

It turned out not to matter. The other riders were all novices on the two-hour ride (I should have guessed from their terrified, dopey grins). I had signed up for the three hour "intermediate" ride, and was the only client.

That's odd, I thought. Why didn't they just send me off with the beginners?

The guide put me on a large brown horse. He mounted a white one and lef me off on a private Zambezi safari.

I carried along my camera, water, sunglasses, and a hat. My sun fears, it turned out, were unfounded. The sun started fading shortly after we left the stable.

the view from the back of the horse

the view from the back of the horse

Almost immediately, we came across a group of guinea fowl and three warthogs. And then, we met up with my first African buffalo.

The buffalo, normally not known for his social skills and accommodating demeanor, ignored us.

To an animal, I was a horse. Sure, I was a funny-looking horse with a strange protrusion on its back, but I was a horse. It presumably never occurred to a buffalo that a human might ride a horse.

The downside to riding a horse on safari is that you can't get a steady shot of anything with a camera. The horse required attention and my horse was especially pesky as he kept snacking every time I loosened my grip on the reins.

On we went, following elephant tracks. The guide showed me how elephant tracks are as different as human fingerprints. We followed some, and not surprisingly, they led us to three elephants.

We watched for a while and then continued on. I propped my sunglasses up on my Woolworth's "one size fits all" stupid hat, and rode through thorns and brambles down to the Zambezi River.

"Look, he's thinking about crossing the river." The guide pointed to an elephant on the opposite bank. A sightseeing boat pulled up. The elephant considered the boat for a minute, appeared to decided the popping flashes were no threat, and studied the lay of the water. He walked in.

The river got deep in the middle and the elephant nearly disappeared. He swam to the other side and then reached a shallow shelf. He hauled himself up by the front legs.

"C'mon," said the guide. "I know where he's going."

I followed the guide downriver. We stopped and waited.

Along came the elephant. He was huge -- African elephants are gigantic -- and his tusks were long. I aimed my Canon.

Then, the elephant spotted us. His face changed. He looked angry.

"He's spotted us," I said. Then, "he's running."

The elephant charged. But the horses were well ahead of him and me. They knew instantly that a pissed-off elephant was chasing us, and broke into full gallops.

I help on tightly and looked back. I had never seen such an awesome, terrifying sight as a charging elephant with me as its quarry. The horses ran like hell.

The guide was laughing, so I suspected that we weren't in any serious danger, and we weren't. The elephant, convinced that he'd scared the daylights out of us, turned away and slowed. We trotted a bit further and slowed to a walk.

"Wow," I said. "Now I know why you take novices out separately." Novices were not taken as close to animals and were certainly not deliberately placed in front of elephants.

And then I felt for my sunglasses. They were gone.

"We'll just go and get them," said the guide. "Hopefully they'll still be there. One time my hat flew away and the elephant picked it up and walked off with it."

The idea of a gigantic male African elephant twirling around my gold Bolle sunglasses with his trunk was appealing. Nevertheless, I was glad to find them intact, exactly where we'd broken into a gallop.

We trotted back to the stable, and I was driven to town. I was too happy to be rude back to the touts and just laughed at them. Of course, they took this as an invitation to dog my steps, so I ducked into a restaurant for an elephant-sized portion of spaghetti.

AUGUST 20

I put my spare junk into a collapsible bag. Raingear, nice shoes, spare soap, and the like were not accompanying me to Botswana.

My spare bag -- no longer collapsed -- and I went to the "Pink Baobab Cafe" for breakfast.

The pink baobab is an enormous, fireplug-shaped tree with a slight mauve color to its bark. Perhaps the cafe had one in its yard, and was named after that. It certainly had tasty pancakes, bacon, and strong Zimbabwean coffee.

I ran the gamut of beggars, souvenir sellers, and money changers, and walked to the bridge that connects Zimbabwe to Zambia. Zimbabwe stamped me out (free for a day) and I walked across the long bridge.

I was not alone. Dozens of locals were walking too, while tourists whizzed by in nimibuses. Lars was in one of them.

We walked over Victoria Falls itself. I restrained myself from taking photos, reasoning that it was a border but later realized that photos were taken all the time at the nearby bungy jump.

The bungy was located right in the center of the bridge. No one was jumping at the moment, but I hoped to see a jump on one of my subsequent visits.

Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls

On the Zambian side, I went through Immigration and walked into "tough" Africa.

So far Africa had been easy. But Zambia was relatively new to tourism, and the immaculate campsites of Namibia and tourist facilities of Zimbabwe were mostly nonexistent on this side of the river. I remembered the tough time I'd had in the last country new to independent tourists -- Uzbekistan -- and hoped Zambia would be easier on me.

Today, however, I was not taking the bull by the horns. I was just dropping off a bag at a hostel.

I negotiated a taxi fare for the ten kilometers to Livingstone -- four US dollars.

A Zambian man and Zambian woman got in. I was sure they weren't paying four dollars.

The cultural shift was instantaneous. The taxi driver and passengers were friendly and curious. No one tried to change money or sell me wooden elephants.

"How are you?" asked the driver. "Where are you from?" asked the woman. The other passenger smiled and nodded all the way to Livingstone.

I got out at "Fawlty Towers". It was no "Club Shoestring." It was quiet, shady, and the staff was efficient.

The woman behind the desk took my bag along with a bed deposit. I'd be back in just over a week.

She showed me a well-marked map of Livingstone and told me where to catch a share taxi back to the border. It was only 2,000 kwacha -- less than a dollar. I'd have to pay using one dollar, as I had no Zambian currency, but that was far better than the quadruple payment I'd made on the way in.

I walked through Livingstone. Short, hot and dusty -- it wasn't much to look at but felt a lot more secure than Vic Falls.

I passed FedEx and ShopRite and approached the taxi stand.

"Borderborderborder," yelled a driver. He already had three people in his taxi, so I got in the front seat.

We drove in silence for five kilometers, and then he pulled over.

"I must check something out." He lifted the hood and pulled out a fuse. He licked it and put it back.

"Sound the horn," he said. I did, and it emitted a feeble beep. The gauges came on and we drove off.

The driver and I chatted en route to the border. I said goodbye, shoved my passport at the Zambian officials, and was stamped out without even a glance at my passport photo.

"Hey!" The taxi driver pulled up. "Want a lift?"

He was driving to Zimbabwe to get a price on spares, and had just changed his taxi plates to regular plates. Lots of Zambians were taking advantage of Zimbabwe's currency problems, to the point where the border turned into a mob scene later in the week and was closed for a few hours.

I left my non-taxi at the Zimbabwe side of the bridge and went to see Victoria Falls from the official viewing park. The entry fee had gone up from when the guidebook was published and was now twenty US dollars or 180 South African rand. I had neither on me, having underestimated the amounts of funds I'd need for the day. I had a few US dollar bills, 400 Zimbabwe dollars, and 150 rand.

Victoria Falls

Victoria Falls

"I need to pay in a combination of currencies," I explained to the cashier.

"You cannot." She frowned.

"Well, then, all I have is 150 rand."

She thought for a minute. She handed me a receipt, took my 150 rand, and said, "that's all I can do."

I thanked her and took the receipt to the ticket taker. He stamped it.

"Is this your first time at Victoria Falls?" He asked.

"Yes," I replied.

"Shame on you! From Zimbabwe and never having been to Vic Falls!"

I smiled sheepishly and went in. When I was out of his sight, I inspected my ticket. I had a local ticket, priced at $50 Zim. The cashier had made a nice profit. That was okay by me.

Later, Lars and Carina told me that I could've paid in Zim dollars at the official rate and my entry fee would've offically been $20US, but at the exchange rate I had gotten on the street, I would have paid less than five dollars US.

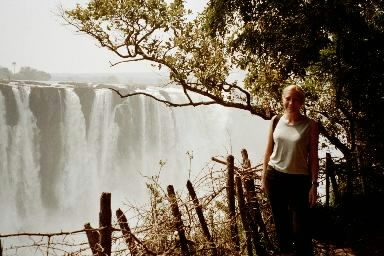

The Zimbabwe park around Vic Falls was atmospheric, lush, and carefully landscaped. The Falls themselves plunged from various rocky outcrops around an island-like rocky lump in the middle. The Falls were enormous, magnificent, and managed to soak me thoroughly with stray spray.

Marie gets sprayed by Vic Falls

Marie gets sprayed by Vic Falls

I walked back to town, and at six met my Nomad group at Savanna Lodge.

The group consisted of two young couples, Dennis the Irish-American ex-banker, me, leader Christine, and an unnamed driver. One couple wasn't there yet, but Christine gave us a rundown of the trip without them.

The itinerary was changing slightly. Instead of returning from Maun, Botswana, on August 26, we'd leave Maun on the morning of the 25th, to stay overnight at a campsite called Baobab. This would break up the return trip, but would take away a day from those passengers leaving the trip in Maun.

I mentioned my food allergies, and was surpised to learn that another passenger had even worse problems than I did. Marcel, the Swiss-South African, couldn't have wheat or rye.

Christine, to her credit, was nonplussed.

"I'll call Thebe River Safaris and see if they can make you a non-dairy, non-wheat takeaway lunch for tomorrow," she said.

The meeting adjourned and I ran to meet Lars and Carina for a goodbye drink.

They had gotten US dollars from the Barclays Bank in Zambia, and paid me back for the entry visas. They told me that whitewater rafting was not to be missed when I came back to Vic Falls, and warned me that the steep climb out of the gorge was hell.

It was sad to part with Lars and Carina. They were going fishing in Caprivi and then flying home to Sweden. As many had pointed out to me, finishing Marie's World Tour on schedule meant sacrificing time with new friends on a regular basis.

NEXT: 70,000 elephants and the Okavango Delta.