Basketball in the Trade Winds

(Marie-Mail entry #41)

BERLIN TO BREMERHAVEN

JULY 15

Packing was easy. I could do it in my sleep, even without all my new lightweight gear. It was unsettling that my laundry detergent outweighed my binoculars.

"How do you pack for a trip like that?" At least twenty people had asked me that. The problem is that on a year-long around-the-world trip, you encounter all types of weather and climate conditions. But you can't carry everything.

The answer is simple. You don't pack for the whole trip. You pack for smaller trips, restocking and re-gearing when the situation calls for it.

My latest re-gearing had left me minus several items of clothing. I'd be living a sparse existence with few luxuries, as my camping and safari gear now took up most of my pack. I had bought technical, light versions of my camping equipment. Unfortunately, nothing I did could change the weight of shampoo, shoes, my first-aid kit, and four months worth of tampons.

I had a "should have bought a Gregory pack" moment when I strapped on my bag, but soon was distracted by my sleeping bag bopping me in the head from its perch atop my luggage.

My evil pack and I locked up Frau Goder's apartment, leaving the key with a neighbor. We walked to the Kotbusser Tor U-Bahn and made our way to the main train station. We left Berlin at five, disembarking three trains later at Bremerhaven.

BREMERHAVEN

JULY 16

I spent the night at Hotel Lehe and made my way to the Bremerhaven center on Monday morning.

The first thing I did was put my bag in a broken locker at the train station, leading to a comedy of errors as I tried to find someone to help me. A man with the right set of keys came along, and soon I was skipping alone to the Maritime Museum, to meet Christina Horn.

Christina Horn

Christina Horn

Christina Horn was the travel agent who had booked me onto the "DAL Kalahari," a 57,000 gross ton cargo ship that was carrying me to South Africa. She was also hunting tirelessly for a ship to take me north from Djibouti to Europe in November. We were meeting for coffee after months of chatting via e-mail.

She turned out to be every bit as charming and hard-working as she had been on the computer, and had rented a car to boot. We picked up my bag and drove to the container port.

Bremerhaven port

Bremerhaven port

Christina knew exactly where the "DAL Kalahari" was berthed. What a switch it was from my experience with boarding the "Direct Kiwi" back in California, when Steve, Cat, and I had driven around cluelessly, hoping to stumble onto the right berth on Terminal Island.

DAL Kalahari

DAL Kalahari

The ship was huge. It carried a maximum of 3300 containers, and had an enormous cooling plant. It was one of the six largest cooling vessels in the world. It was outdated now, but had been the pride of the fleet when built in 1978.

The "Officer's Smoke Room," unlike the tiny closet with a VCR on the "Direct Kiwi," was a large room with a full bar and entertainment center. The Captain's dining room was separate from the Officer's dining room, which in turn was separate from the crew's dining room. All resembled genuine restaurants. The passengers sat with the Captain, Chief Engineer, and Chief Mate at meals. There was only one problem.

ship's passage

ship's passage

I was the only passenger.

The ship wasn't leaving until night, so I left my bag in "Single Cabin #1" and headed back to Bremerhaven. Christina dropped me off and went to take the train home to the Black Forest.

I used up my German Marks quickly in Bremerhaven, buying some snacks for the trip and a takeaway salad for dinner. I hunted for the ideal crushable, lightweight, wide-brimmed safari hat but had no luck (I'd made the mistake of NOT buying a Tilley Hat in the States and had been regretting it for months). I spent an hour walking back to the ship, which took me past auto shipping yards, where drivers sped Mercedes and BMW's across ramps onto giant ships.

Finally, I arrived back at the port. I caught the shuttle bus back to the ship, and settled into my cabin.

At 9:30, my phone rang.

loading

loading

"This is the Captain. We are about to leave port. Would you like to come up to the bridge and watch?"

Up I went, to see the tugboats pull us out and to watch the Bremerhaven pilot issuing instructions to the helmsman. If you've never seen this operation, it goes something like this:

"325," says the pilot.

"325," says the helmsman, making these adjustments on a console. The Captain hangs around and supervises, and the Chief Mate is usually there too. The ship moves slowly as it leaves the harbor.

A few minutes later the pilot issues new numbers, the helmsman repeats them and makes new adjustments, and so on, until the ships clears the harbor.

crew at work

crew at work

The pilot goes below deck, where a watertight door opens to his special pilot boat (marked "P" for, well, you know). He goes away, to pilot another boat out of the harbor. The ship continues on under its own navigational power, and land recedes in the distance.

While the pilot was doing his thing, the helmsman interspersed setting a course with talking to me.

"Where is your friend?" he asked. "There were two of you earlier."

I explained that my friend had just been dropping me off, and had stayed in Germany.

propeller shaft

propeller shaft

The Captain was going over some stuff with the new Russian Chief Mate, who had just joined the company and the ship.

As soon as we were underway, the Captain left the Chief Mate to his first-day jitters and approached me.

"This may seem a little strange, but I have just gotten here today, and the other Captain has just handed the ship over to me. I haven't had time yet to review all the paperwork. So... where are you going and do you have a valid passport?"

Chief Mate and Captain at work

Chief Mate and Captain at work

"Cape Town." I laughed, appreciating his sense of humor. Captain Gaebe was not just from my generation, he was the same age as me, and had spent a year studying in New York state. He was German, but lived in Buenos Aires with his Argentinean wife, stepson, and newly-adopted dog. He was on relief duty, meaning that he worked for six weeks at a time, giving Captains the chance to take a holiday while he oversaw their ships. He had spent time on the "Kalahari" as a second and first mate, and knew the ship and crew well.

But most importantly, when I explained that I was going around the world by surface transport, the Captain did not say""you are mad." He said "that's cool." It was going to be all right to be the only passenger for the next fifteen days.

AT SEA

JULY 17 to 20

I awoke to the familiar rumble of a ship's engine. The room was swaying slightly, but my days of being seasick were over.

At breakfast, I met Mr. Asuncion, the Filipino messman whose responsibilities included playing waiter to officers and passengers, and cleaning my cabin. He was also new to the ship, and pointed me to my seat -- indicated by the word "passenger" written on an envelope. The envelope contained a cloth napkin. There were similar ones for "chief mate," "captain," and "chief engineer," but for the morning meal, only the Captain and Chief Mate joined me.

dinner at the Captain's table

dinner at the Captain's table

"I thought there were two of you," said Mr. Asuncion. "Where is your friend?"

"She is not on the ship. She's the travel agent."

The Chief Mate introduced himself as Vladimir, as the Captain had introduced himself as Martin. But I could never bring myself to use their first names, and always addressed them as "Captain," and "Chief Mate." There were around 24 other people on board, but I never did meet them all or figure out what each one did.

Over the next few days, the paper envelopes were replaced by new ones with typed identifiers. "Captain M. Gaebe," said one. "C/O V. Kornilev," said the other. And "C/E B. Soehnle." Mine still said "Passenger."

Finally, I showed up for a meal and "Mrs. Javins" had been added under "Passenger." The messman explained to me that he cleverly copied it off of my cabin door. I tried to explain that I wasn't my mom, but she isn't Mrs. Javins either, and then it got to confusing for even me to follow so would just have to settle for being called "Mrs."

The Russian officers that had escorted me across the Pacific had made the best of being at sea for six months at a time, but they had resigned themselves to it, and didn't consider it the least bit fun. The Filipino crew on the "DAL Kalahari," on the other hand, were all smiles. These were men who would enjoy themselves no matter what, as evidenced by the basketball net on deck and the occasional sounds of electric guitar that I heard at breakfast.

Kalahari stacks

Kalahari stacks

"Why is there a basketball hoop on deck?" I asked the Captain, during one of our twenty-five meals alone. The Chief Mate had quit showing up for meals, preferring to eat quickly in the pantry, and the Chief Engineer only joined us at dinner time.

"Filipinos are crazy for basketball," he said. "But they are also crazy for ping-pong and music and everything else. It goes in waves. Sometimes it is basketball every night and sometimes it is marathon ping-pong tournaments."

The Filipinos also had a saying. When a European takes up a sport, they'd say, the first thing he'd do is buy expensive shoes. But when a Filipino played a sport, he'd just wear his flip-flops.

I witnessed this one night, when some crew members put a large net around the railing (to catch stray balls) and played a basketball game. Two played in flip-flops, and they performed just as well as the three in snazzy sportswear. All five were oblivious to the steady movements of the deck.

basketball on deck

basketball on deck

I spent my evenings in my cabin, watching videos from the ship's library. In the mornings, I'd have a walk around deck, through the passageway under the containers. It was a rusty ship, and men were constantly battling the elements to de-rust it.

The good news was that we were going to make two stops in the Canary Islands. The bad news was that the only Tenerife berth big enough for our ship was occupied. We would have to slow down, get there early in the morning, unload, and leave at ten a.m. I would have no time to go ashore.

CANARY ISLANDS

JULY 21

All I saw of Tenerife was the parking lot at the port. I took a quick walk, determined there was nothing to see, and got back on the ship.

Tenerife port, Canary Islands

Tenerife port, Canary Islands

Four hours later we were in Las Palmas. A woman with a large bag was waiting for us. I thought she was from the shipping agency.

"No," said the Captain. "She is carrying things to sell to the crew."

"You're kidding," I said. I must have looked shocked, and I was. This was just like riding trains all over the world.

"No, no," he added. "It's good! She sells phone cards and things the men need. I am glad to see her, because I have forgotten my alarm clock."

He called a taxi to come for me, and the Chief Engineer gave me a map of Las Palmas.

moving a floor

moving a floor

My first stop was the "cambio" or "banco." I had no pesetas to pay the taxi driver. I insisted on speaking my inept Spanish to him, and he constantly begged me to speak in English.

"English, English!" he'd say.

"Cambio, y playa." I'd respond. I wanted to get money and then go to the beach.

"Okay, which one first?"

When he did drop me at the beach, he refused to take any money from me.

"Tarifa?" I asked.

"No."

"Agencia?" Maybe the shipping agency was paying for this.

"No. No tarifa. My gift."

Okay. I was used to haggling and arguing with taxi drivers. This wasn't what I'd expected at all. The driver even wrote down the name of the container terminal (in Spanish) and gave it to me, so that I could get back later. I liked Spain.

Las Palmas, Canary Islands

Las Palmas, Canary Islands

I wandered down the packed beach to the main shopping street. I window-shopped, mailed postcards, ate a sandwich, and tried to absorb the local flavor. There's only so much you can get out of six hours in port, but it was nice to get a taste of the Canary Islands.

After dark, I flagged down a taxi. We were leaving at midnight, and I didn't want to miss the ship. I showed the taxi driver the note with my destination written on it, and he got excited. Clearly, driving into the container terminal wasn't something drivers got to do every day.

This taxi driver spoke non-stop Spanish to me and I struggled to keep up. When we got to the port, the gatekeeper got on his motorbike and escorted us to the ship. I was the last one to sign in. I asked the Captain about this later.

"It depends on the crew," he said. "Some crews are out boozing in port, but most of the ones I've worked with are different. They are working hard for their money and don't want to blow it."

We left the Canary Islands while I was asleep.

AT SEA

JULY 22 TO 25

Something was wrong. I looked out the window. We weren't moving.

At lunch, I asked the Captain about this.

"Captain," I said. "Why are we sitting still in the middle of the ocean?

We weren't actually sitting still. We were going five knots an hour, running on one of our two engines. The engineering staff was changing a cracked liner (in one of the piston shafts), so we'd be going at five knots until evening.

at sea

at sea

The engineering staff for a two-engine cooling ship was big. We had, in addition to the Chief Engineer, a First Engineer, two Second Engineers, and one Third. They were all very pleased with their work when they'd finished, as they had set a ship record for number of hours taken to change a liner.

I learned a lot from eating two meals a day with the Captain. I learned about Germans, Argentineans, and Filipinos. We compared the German and American school systems, talked about the integration of East and West Germany, ate German food on weekends, and I grilled him endlessly about life at sea.

"How can you navigate by the stars? How does longitude and latitude work? Is it common for seamen to divorce (like two of our officers)? Will we see dolphins? Will we see whales? Why are so many ships registered in Liberia? What would happen if Liberia fell? Why did you go to sea? Is it hard for your wife? How does GPS work? Why are so many crews from the Philippines and Russia?"

He must have gotten tired of me asking all of these questions, but put up with it well. He told me about the Mombasa safari guide, who takes crews on short safaris (they all love it), and about a bosun who had kept pigeons on board a ship. We had our own pigeons for a few days, and crew members were sneaking them rice and water until they flew away near Dakar.

Chief Engineer Soehnle

Chief Engineer Soehnle

One story was of a sea captain on the West Africa route. A ship makes its own fresh water, and has an almost never-ending supply. In port, Africans were always coming by and asking for cups of fresh, healthy water. Finally, the Captain just stuck a hose over the side and invited the locals to help themselves. But then the police came and put a stop to it. Water is big business in West Africa, and people were filling up cars full of containers, and others were not getting their share. It was causing riots, and the crew had to go back to doling it out a cup at a time.

JULY 26

Grill party tonight!

"Those aren't the right words, are they?" asked the Captain, who had typed the day's menu.

I considered it, and decided that "grill party" was okay. "Barbecue" is often used to describe a outdoor grill party, but being a Virginian by birth, I consider barbecue to be something slow-cooked in a pit. There was no barbecue pit on the ship.

barbecue on deck

barbecue on deck

The Germans and Russians (and sole New Yorker) sat at one table, while the Filipinos clustered around three tables (by department and age). Everyone ate chicken, steaks, and potato salad. The ship's guitar, amp, and karaoke system had been brought out on deck. I was starting to think that the shipping company liked to keep their employees happy. The crew had been lobbying for a set of drums, and they just might get it.

The motorman, a ten-year veteran of the ship, was (as he always is, apparently) the master of ceremonies. He welcomed everyone to the party and introduced the entertainment.

First Passenger, First Engineer, Chief Engineer, Captain

First Passenger, First Engineer, Chief Engineer, Captain

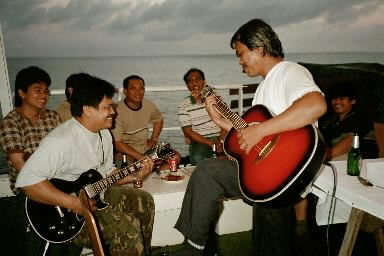

One of the cooks played the electric guitar (more or less), and was accompanied by a man who was just learning. It was a dreadful racket, but everyone clapped because they were trying, and it was different than the usual night's entertainment of ping-pong and videos.

musical accompaniment

musical accompaniment

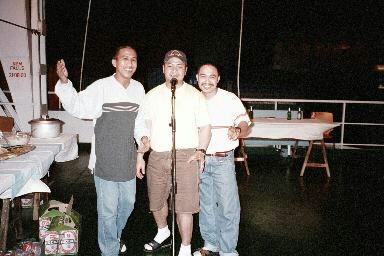

Then the karaoke kicked in. The motorman made it a contest, between the engineering staff, the deck staff, and the kitchen staff. Some of the crew tried to hide so that they wouldn't be asked to sing, but others leapt to the challenge and belted out sappy ballads in style. Watching a young Filipino man who had never been to the Shenandoah Mountains give an emotional rendition of "Almost Heaven, West Virginia" in the middle of the Atlantic brought me to tears. Not really, but it did give me a bad case of the giggles.

Filipino karaoke

Filipino karaoke

The Europeans -- including myself -- declined to sing. But I was joining the Captain and Chief Engineer in my admiration for the crew.

"They don't care if they make a fool of themselves," said the Chief. "They just want to have fun."

He was right, and the crew continued to have fun after every German and Russian had gone to bed. By the time it was just me and the Filipinos, the youngest ones were dancing.

The rest descended on me.

"Where is your friend? We thought there were two of you."

"Why did you choose this ship? Why are you traveling this way? Have you met a Filipino before? What do you think of the Philippines? Why doesn't the U.S. send in the Army after the men who took the Americans hostage?"

I was being asked several questions at once from all directions and struggled to answer them all.

ship's promotional postcard

ship's promotional postcard

"Please tell people that if Okinawa does not want the U.S. military there, the Philippines would welcome them back. And tell people that not all Filipinos are like the Muslims who took the hostages, and not all Muslims are bad. What did you do before you left New York?"

I told them that I had been in comics, and had worked with several artists in the Philippines, including one who was famous in U.S. comic circles. I showed my comic-book style Marie's World Tour postcard, and they all decided they needed one each -- signed. I spent the next hour trying to write clever dedications on the back of postcards.

on deck

on deck

Finally, I pleaded exhaustion and went to sleep. Looking back, I could see that they were still dancing.

JULY 27 TO 30

"Why does the crew keep asking me about my friend?" I asked the Captain.

"They were very excited to have two young lady passengers on board."

I was sorry to have disappointed them.

anchor

anchor

Our meals were becoming progressively less fresh and more canned. Strawberry desserts had given way to canned peaches. The bread all had a defrosted taste to it. And I was beginning to repeat myself in conversation.

The Chief Engineer always came to our rescue at dinner time. He had gone to sea in 1965 and would tell us amazing stories about the old days.

"Before everything was containers, loading and unloading could take days. Back then, people went to sea to see the world," he told us.

Now all they'd see was the Seaman's Club, or if they were lucky, they'd get a whirlwind tour through a port city.

The Chief Engineer had started his career in West Africa.

engine room

engine room

"Back then we would take brandy and a case of beer, and take a small boat up a river into the jungle, until we came to a village. We would give the Chief the brandy, and then hang around and drink beer with the natives. But they always kept their women hidden."

Later, he had worked on the small cement ships that service the East African islands out of Mombasa, Kenya.

"There was one woman who lived with her husband on an island. Whenever our ship was in port, she would have a dental emergency and have to go to Mombasa. We thought that she must have bad teeth! Later, we found out that she was having an affair with their second officer."

Another story was about a pig farmer who left his pigs behind on an island. They'd ran wild, breaking their teeth by eating coconuts. The sailors wanted a pig roast, so had gone there and caught a pig. They got the pig back on board but it was very skinny and you could see its ribs.

"You can't eat that pig, you idiots," said the Chief Engineer's wife, who sometimes joined him at sea. "She's pregnant!"

So they had made a pigpen and fed the pig the coconuts it liked (opening them first). Five piglets were born, but the mom pig rolled on three and crushed them. The sailors rescued the other two. The Chief's wife adopted one, feeding it with a bottle and babying it.

a woman in the engine room

a woman in the engine room

When they got to Mombasa, they had a problem because the authorities wouldn't let livestock in. They had to give the pigs to another ship.

"My wife was crying and crying. The pig was her baby."

"Shipping changed about ten years ago. Now everything is in to port, out of port quickly. There is hardly time to go ashore and it is all about the schedule. No one wants to go to sea now, because it has not been fun for ten years."

"That is exactly as long as I have been in shipping," said the Captain, ruefully.

CAPE TOWN

JULY 31

There was someone in our berth again. We'd have to delay our arrival into Cape Town.

approaching Cape Town

approaching Cape Town

First, we slowed down. There was no point in arriving early, as we'd just have to drift or anchor until the berth was vacant.

Then, headquarters sent an e-mail for us to hurry. There was another ship due in, and we needed to be in line ahead of her. We were to hurry up so that we could wait, drifting outside the port until after midnight.

We approached Cape Town, and then turned. Would we anchor or drift? The advantage to anchoring was the Engineering could shut down the engine and make repairs, or possibly relax. The problem was that if the wind was strong and the surface was sand instead of mud, we could get blown into a beach. So the Captain would have to survey the conditions and make a decision.

Then, everything changed again. Suddenly a berth was available and we were to begin our approach at 1500. Then everything changed again -- the pilot was not available until 1700. I was already planning to spend the night on the ship, as we'd already had the ship's travel agent alter my hotel reservation twice, but I was hoping to get a meal that didn't come out of a can or the freezer.

We ended up in port just after dinner time. The sky was clear and bright, but a strong wind served a a reminder that South Africa was in the midst of winter.

docking

docking

"The weather was perfect yesterday," observed the pilot.

The immigration officer showed up without his stamps. He took my passport (the new one, the old one being at the Ethiopian embassy in Washington D.C.) and promised to drop it by later.

Cape Town looked lovely. Everyone else with shore leave left the ship. I read a book and waited.

I waited for a long time.

NEXT: A list of reasons (courtesy First Engineer) that women should not work in Engineering! A new and innovative approach to the unearned accumulation of US currency. And finally, land ho!