Detente on the Seas

Location: the Pacific Ocean,

more or less near the Equator

January 21

Today was my third day of going patchless. That must

mean that I've gotten my sea legs.

The ongoing controversy was over the total silence

of the Russian First Officer, affectionately (and

quietly) referred to as "Giggles." He ate at least two

meals a day with the passengers but barely ever spoke.

Fred, who sat next to Giggles, had tried talking to

him with no success, and had even tried changing

places with me. I'd had no success with the young man

either. Even worse, he had practically swallowed his

meal whole and ran from the room when I sat down next

to him. I suggested to Roland that Giggles knew very

little English, and Roland agreed to get one of the

other crew members to teach him some Russian.

It was Jo's 60th birthday, and the cook had made her

a cake. Roland had learned some Russian, and he asked

me to say it at breakfast, but he told me it meant "do

you handsome Russian men like blondes? I am a blonde."

The night was clear, and with no light source save

the ship and the stars, Venus reflected on the waves.

January 22

When Giggles came to breakfast, I greeted him with a

competent "dobro yeah utro"-- good morning in Russian.

He laughed and said "dobro" back. Success! He hung

around longer than usual, and as he left, addressed

the room.

"Good night!"

The whole incident seemed to support my

language-barrier theory rather well. But he could have

just been flustered.

We had passed the equator in the night, and the

attitude of the Russians had changed instantaneously.

They had been quiet and surly, but now they stripped

down to their bikini briefs and became goofy, chatty,

normal, young men. The second officer did pull-ups to

impress Roland and I. Giggles lay almost naked on the

steps, eyes closed, basking in the sun like a furless

sea lion. I almost stepped on him, and beat a hasty

retreat, wondering if it would be proper to photograph

nearly naked Russian seamen without their consent. An

albatross adopted our boat, flying around and around.

As usual, the Sri Lankan crew members wore their

orange jumpsuits, white schmattes, and continued to

work. The tiny swimming pool was filled, and I sat in

the bow chatting with the Chief Engineer.

View from my window

"Have you ever encountered pirates?" I asked the

Chief. Pirates were the flavor of the month back home,

as they had gotten press in some magazines and in the

New York Times.

"Yes, but not on this ship." He continued on to

explain that the pirates don't actually show their

faces. They sneak alongside in a small boat at night,

and when everyone is asleep, they rob the containers.

The pilot up in the Bridge doesn't spot them until the

boat is speeding away.

"But what if you catch the pirates?" I asked.

"I don't know," said the Chief, very seriously.

After dinner that night, I decided to forego my

customary loss at cards and watch "The Perfect Storm"

instead. My cabin had no VCR so I barged into the

Officers Rec Room, surprising the astonished second

officer who wasn't quite sure what to do with me. He

motioned to go ahead and put in the video, and the

other officers came in. Most of them saw me, looked

surprised, and left, but Giggles and the Second

Engineer came in. They'd knew I didn't bite.

I fast forwarded over the plot. I'd read the book and

seemed to be the only person on Earth who found it a

tough read. I was there to see the storm. It started

dramatically, with a container ship like our own

losing containers to the sea. The seamen watched my

reaction. I gave them a frightened whimper - it was

what they wanted.

A minute later they were laughing and pointing - the

Andrea Gale was rocking in the gigantic waves, but the

food and coffee cups stayed glued to the tables.

Later, after watching Hollywood overdramatize the

last moments of some dying men, I chatted with my

Russian pals.

"What do you guys do for fun on this ship?" I asked.

"That is a very good question," said Giggles in his

halting, brusque English. They had no answer.

They explained to me that they all worked in

six-month increments, and all the Russians came from

the same maritime academy in St. Petersburg. The

second officer invited me to the Bridge during his

watch.

I asked them what they did on their shore leave in

Long Beach. They had taken the subway from Long Beach

to Los Angeles, where they'd gone to Universal

Studios. They told me a joke about a Russian who went

to America. He'd returned home and said, "in America,

they use the same currency we do, but instead of

calling it bucks, they call it dollars." I learned

that the name "Brighton Beach" always makes them

laugh.

The Chief Engineer stopped by to tell me about a

movie that he'd just been watching with the Captain.

"It reminds us very much of you. It is called Coyote

Ugly."

I had to admit that the real Coyote Ugly Saloon was

about four blocks from my home in New York, but I

can't imagine what about that movie reminded them of

me.

January 23

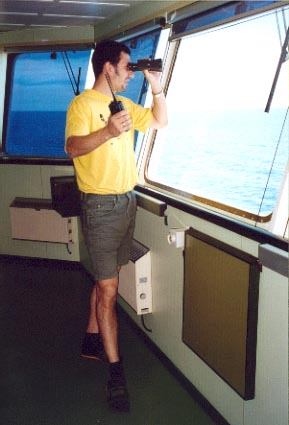

Evgeny at work

I visited the second officer on the Bridge. His name

was Evgeny, not Boris, but Giggles name was, in fact,

not Giggles but Boris. I stifled my own giggle.

The Direct Kiwi was traveling at around 20 mph, which

is apparently good, although to me it seems

excruciatingly slow. Evgeny showed me weather charts

and navigation charts, and I sort of understood after

he explained how they worked. He told me that the

Russians all hoped to hang onto their jobs, because

they are very good jobs.

At dinner, I asked the Captain why the crew was all

Russian and Sri Lankan.

"Europeans don't want the jobs," he explained. "But

in Russia, where the average monthly income is $30 a

month, this is a very good job. And in Sri Lanka, the

average monthly income is $50-80 a month. The crew

goes home with a few thousand dollars at the end of a

contract."

I finally won a card game, but it was a low payoff

one. I could quit teasing the second engineer for a

loan, and pay my own way for the next two nights.

Nightly card game

I went out on deck to watch the stars and the added

attraction of heat lightning. I'd made the leap from

frenzied New Yorker to relaxed traveler easily enough.

But as a freelance artist in a fringe, cultish

industry, living in a bohemian Manhattan neighborhood,

I barely operated in normal society anyway. It wasn't

such a large leap to take. And I was making friends,

but not the kind you keep. Just the transient kind.

Never alone, but always alone. My self-imposed fate

for the coming year. I was too philosophical tonight.

It was time for bed.

January 24

After being beaten for the fifteenth time in

ping-pong, I left Roland and went up to the Bridge. I

asked Evgeny to teach me to say "crazy chicken" in

Russian, and proceeded to get mileage out of it for

the rest of the day. Only the Californians truly

understood "El Pollo Loco," which is the name of a

fast food chain in the western US, but the Russians

saw humor in it too. Seems "crazy chicken" is funny in

any language.

Over dinner I was introduced the world of senior

jokes. One went like this.

A group of senior women are hanging out. One woman

says, "I'm getting married again." The others say,

"that's wonderful. Is he handsome?"

"No," says the woman. "My first husband was better

looking."

"Well then, is he rich?"

"No, I have more money than he does."

"Is he good in bed?"

"He's all right. Nothing special."

"Then why are you marrying him?"

"Because he drives at night!"

(Seniors howl with laughter.)

I also asked the Captain if they ever had stowaways.

He explained to me that it does sometimes happen,

especially in very poor countries. The stowaways hide

in the containers, and if caught, the ship owner must

pay to have them repatriated. There are also a lot of

laws about the treatment of stowaways, who must be fed

and well cared for.

I finally won the card game of "Screw Your Neighbor."

The mega-jackpot was $2.40. I won fair and square, but

was brought soundly back to earth a few hours later

when the Russians tried to teach me a card game and I

couldn't understand the rules. It might have been a

language problem, as the boys kept telling me to

"attack with a six of cubes, but the heart is the

powerful card." They warned me to not go around saying

"crazy chicken" in Russia.

January 25

It had started raining in the night, and the entire

ship was coated in drizzle. Roland had given me a

project: to find out how to say "deodorant" in

Russian. Our crew was healthy-smelling, and they

worked hard. But I wouldn't have the nerve to ask. I'd

have to learn "invisible pig" instead, in honor of my

trip mascot.

Unfortunately, I was not capable of glibly rolling

"nevedemaya svinka" off the tip of my tongue.

"Invisible pig" was not the success that "crazy

chicken" had been. I sat up late with Oleg, the

26-year-old second engineer, explaining my invisible

pig, el pollo loco, and comparing life in St.

Petersburg with life in New York.

Officers at work

Oleg, somewhat of a prodigy, had worked hard and been

promoted to second engineer in a short amount of time.

He wanted the same things that American 26-year-olds

want. He was saving to buy a flat in St. Petersburg,

and he wanted a powerful, new computer. He knows that

Russian salaries "are shit," and that is why he and

the others can stand to be at sea for six months at a

time.

"Sometimes I lay awake at night and ask myself, what

have I done today? And it is nothing," he explained.

"But I have chosen this life, and it is only for maybe

five years more."

He explained to me that for people his age, the new

Russia is much better than the old Soviet Union. His

parents, like others their age, have very little to

show for their years of teaching and factory work.

They live in a small apartment on the coast. But he,

and others his age, have the opportunity for much

better lives. Still, life was hard in Russia and he

had considered emigrating but wasn't sure where to go.

As a sailor, he had been all over the world, but often

his shore leave was only six hours. He would spend

that buying supplies.

"I have been everywhere, but I have been nowhere," he

explained.

January 26

I brought a pack of Famous Amos Chocolate Chip

Cookies to the nightly card game. The other passengers

went to their cabins, and I stayed to watch the fate

of the leftovers.

A certain furry blue Sesame Street character made an

unexpected appearance when the officers walked in.

"Cookies," they yelped, descending on them. This was

a real switch from the first time I went abroad, to

Finland in 1982. My Finnish friends had never heard of

chocolate chip cookies.

We watched "Coyote Ugly," a hopelessly silly

semi-sweet, semi-soft-porn love story about a naive

songwriter in tight pants, who inexplicably dazzles

hordes of drunken sailors by singing along with a

Blondie CD. One of the characters collected comics and

was obsessed with the first appearance of the Punisher

- that had reminded the Chief Engineer of me.

I continued my conversation with Oleg, now stuffed

with cookies.

"A ship is no place for a woman," he explained by way

of apology. One of the other officers had been a

little drunk and teased me more than usual, crossing

the line into inappropriate behavior. They had tried

to laugh it away by blaming it on his supposed

affiliation with the Chechyn mafia.

"But what if there were many women? And it was not

unusual? Then it wouldn't be a big deal," I argued,

even though a part of me traitorously agreed. People

tend to lose their minds when cooped up together for

months. I'd seen it on overland truck trips, where

passengers went a bit mad and did stuff they'd never

do normally.

"What if," I continued, "a woman was a better

engineer than you? Why could't she work with you?"

He laughed. "I have heard of emancipation in the US,

but Engineering is NO place for a woman. We get very

dirty. We get grease all over, and under our

fingernails."

Those were fighting words and I argued with him until

I was explaining internal combustion, four-stroke

engines, and manual chokes (faking it mostly, and

banking on the language barrier to cover me).

"Okay, okay! I am wrong. You are an independent

woman. YOU can work in the Engine Room."

He then asked me to explain the recent US

presidential election. I settled in for a long night.

January 27

The whole day disappeared, swallowed up by the

International Date Line.

January 28

We completely lost Saturday, which was a very lucky

thing because Sunday is pancake day. Pancakes were a

highlight on the "Direct Kiwi."

As passengers, our sea life was pretty slow. We ate,

we slept, we played cards. Every day I lost at

ping-pong to Roland, the oldest passenger on board.

Every day the Russians got braver and teased me a

little more.

Today's "tease Marie because she's the only female

under 60 we've seen in months" session involved a

dried fish. It's a snack, and four of the crewmen,

after a swim in the ship's small pool, were hanging

around drinking beer and eating dried fish. In tiny

bikini briefs. I found a lot of reasons to admire the

sky and ocean.

"Here, eat this. It is for you," they said.

"I can't. Allergy. Fish makes me sick."

A moment of Russian thought.

"Maybe dried fish doesn't make you sick."

"No thanks."

"Okay, then. I sign it, give it to you, you e-mail it."

Now it was just getting goofy. I tried to exit

gracefully, but the whole situation had just become

silly and everyone was laughing as I went back to my

cabin.

January 29

After breakfast, I was sitting in my cabin. Suddenly,

something changed. The low rumbling I'd heard for

thirteen days slowed to a faint background hum.

Nothing was rattling. What was wrong?

I went out on deck. I saw yachts, sailboats, and a

low mountain in the distance. We were in New Zealand,

and were about to get a day on dry land.

Tauranga

NEXT: the mundane becomes spectacular. An exciting

visit to the Tauranga post office, bank, and grocery

story.